Nathan Schmidt died after spiraling toward Earth under a broken canopy of silk that so many times before had lowered him safely to the ground. But on his last jump, the thin material, the stitches, or the cord failed and the cost was Nate’s life.

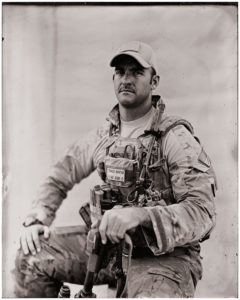

Photo Credit: Ed Drew at eddrew.com

Nate was a large, hairy man with a smile that reeked of sarcasm. He purposely wore Speedos around the team room and you couldn’t tell where his stomach hair ended and his pubes started—but that was the point. He was grotesque, a personality that threatened instant criticism of anything said that could be twisted by his rolling mind. But Nate’s eccentricities created a contrasting foundation for his career as an Air Force Pararescueman (PJ) and a life that pursued purpose.

October 14, 2015, a quote by Charlotte Kaufman on the memorial page setup after Nate’s impact with Earth:

Thank you for jumping into the Pacific Ocean to help my youngest. Thank you for sitting on our boat for 2.5 days listening to my 3 year old’s jokes. Thank you for carrying her safely on your back off of our boat. We are forever grateful. Rest In Peace big, tall, Nate.

In March of 2014, the Rebel Heart, a sailboat carrying a family of four including two little girls set sail for New Zealand from Mexico. Approximately 1100 miles from shore, the youngest girl became sick with salmonella. A distress signal was received by the Navy but they were still days away. So, Nate and three other PJs boarded a C-130 with parachutes and jumped into the massive Pacific Ocean to provide aid to the sick little girl. She survived. The eldest girl, named Cora, was three at the time and Nate became her immediate gigantic teddy bear, using his childishness to keep her busy and distracted from her ailing sister.

After Cora learned of her hero’s death, she asked her mom if they could build padded structures for all the soldiers to land on from now on.

October 16, 2015 as quoted by Duncan Mathis, a Marine wounded in Afghanistan after finding himself 80 feet deep in a well:

I had more broken bones than I could count, I was covered in my own blood, I was alone in the dark, and almost at my breaking point. Then I heard Nate. He reached the bottom and as he put me in the harness he radioed to his team, pulled me close and said, “Matty, this is gonna hurt. I know you think it can’t get worse, and I’ve given you as many pain killers as I can. But brother, this is gonna hurt. You can do this. My team’s waiting for you topside, and I’ll be right behind you.” As I listened to him, everything else faded away.

Nate reached out to Duncan when they were both stateside, asked him how he was doing, and offered to buy him a beer if he was ever on the west coast.

What a strange creature to be such a hero—a body like Sasquatch and a personality laden with sarcasm and vulgarity. His funeral followed the orders of his will which included Hawaiian shirts and flip flops as dress code, two large men singing Dust in the Wind, and another man playing the bagpipes who had never played them before. We were all the butt of Nate’s last joke.

October 11, 2015, among the green lawns and sprinklers of a neighborhood near Santa Cruz, California:

A man reported hearing a yell and then a thud. Nate landed in the neighborhood with his canopy scraping against the concrete in the wind. He was pronounced dead on scene.

The key is that yell. That was no yell. That was a hysterical bout of laughter.

Nate knew what death meant—grown men would cry in their wives arms—and the team room, well it would be much quieter.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2024 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.