President Hamid Karzai, Afghanistan’s embattled head of state, recently revealed a laundry list of political demands he intends to put forth as preconditions for continued US military involvement in Afghanistan past 2014. These demands include financial incentives, security guarantees, a stipulation that US military members will not enter Afghan homes, and apparently some kind of US apology to the people of Afghanistan.[1]

To those of us in the US, particularly we veterans who served on the ground there, these demands seem completely unfeasible and the Afghans themselves unreasonable and ungrateful. Afghanistan’s latest political demands, while frustrating, infuriating, or perhaps even ridiculous-sounding to those of us in the US, are utterly rational, understandable, and perhaps even necessary from the Afgan perspective, especially if one understands the dynamics of the two-level game of negotiations in international relations.

Endeavoring to understand the complexities of international relations requires an understanding of some of its fundamental assumptions and conditions. One of the first assumptions about the international system is that it is anarchic in the sense that there is no ultimate power higher than the state.

A second assumption is that the number one goal of a state is survival, and hence security is paramount. A third key assumption is that the people and leaders of states, and by extension states themselves, are rational actors. Because of the conditions that result from these assumptions, we can conclude that for the most part, states are rational actors that exist in a self-help system where the survival of the state depends on how well it can ensure its own security.

States do not exist individually in this system. They all can affect, and be affected by, each other. Trade, warfare, and alliance building are all examples of the interplay between nations, and all of these interactions require some sort of negotiation between states. Typically, strategic-level international negotiations take place directly between heads of state, or through subordinates appointed to act on a specific leader’s behalf.

These heads of state, or their delegates, negotiate the best deal they can for their own sides and bring the best outcome possible home to their domestic constituencies. If all sides are satisfied with the outcome the deal holds; if a veto player at any level of the process is dissatisfied, the deal fails.

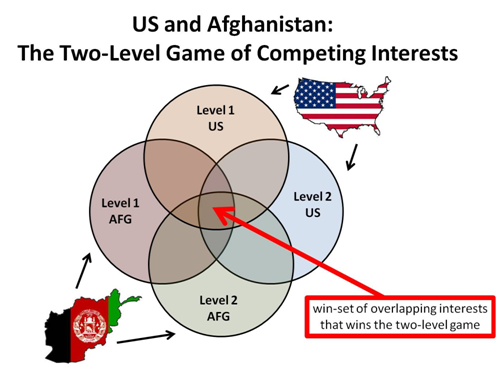

This is where an understanding of Game Theory becomes useful. As explained by Roger Putnam in his article “Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: the Logic of Two-Level Games,”[2] reaching consensus on strategic issues is so difficult because international agreements aren’t won or lost solely on whether or not international leaders can hammer out an agreement at the international level (Level 1), they also have to ensure that they can win the game of domestic politics (Level 2).

Without winning both levels of the game, the game is lost in its entirety. Perhaps the best evidence of this is the ill-fated League of Nations. President Wilson of the US successfully negotiated the League of Nations agreement at the international level, but was unsuccessful in getting it implemented back home. Therefore, his plan was not implemented.

Key to winning the two-level game is the creation of a winset (a margin of acceptable outcomes) that can satisfy (or at least satisfice) the key players on both level of the games. These win-sets must overlap, or there is no room for satisfactory outcome. Sometimes overlap simply isn’t possible. Sometimes leaders can’t agree at the international level (Level 1). Sometimes one or the other domestic constituency can’t deliver (Level 2). But if an agreement can meet the requirements of both levels on both sides, then and only then can the agreement take effect.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2024 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.