Stone Soup, by Marcia Brown, a Caldecott Honor Book first published in 1947.

“Many thanks for what you have taught us…” the peasants said to the soldiers.

“We shall never go hungry, now that we know how to make soup from stones.”

Stone Soup is a tale that has captured the imagination of generations of children and adults alike. For those unfamiliar with the book, as the name implies, it is a clever tale about soldiers and soup, purportedly made from stones. The story offers, in a humble anecdote, a reflection on how to approach problems, treat people, and cultivate creative solutions to overcome obstacles. It is a guidepost, helping to illuminate some of the finer points of building rapport and working with people.

Whether surrounded by allied soldiers in the field training or briefing a U.S. Embassy Country Team, understanding human behavior and cross-cultural communication are critical skills essential to every Special Forces soldier. Stone Soup offers salient, albeit whimsical, spoonsful of wisdom for dealing with strangers, in strange lands.

The story of Stone Soup is an old folktale, that has been told in several countries with various lead characters and different contexts. The story spans a number of cultures, with the premise of the story centering on an individual, or individuals, utilizing their wits to beguile seemingly naïve and unsuspecting individuals into providing ingredients for soup made solely from stones. In some countries, the individuals are portrayed as travelers or pilgrims, while in Hungary, Russia, and France, these travelers are portrayed as soldiers. It appears that even General George S. Patton was familiar with the story, having used the idea of “rock soup” to incrementally obtain resources for his beloved 3rd Army as they campaigned in Europe during World War Two.

The story begins with three soldiers in a far-away land on their way home from “the wars.” They are traveling on foot with their arms and kit, with extraordinarily little in provisions (a familiar predicament to soldiers throughout the world and throughout history!) Spying a village off in the distance, the three decide that their best chance to obtain something to eat is at this local hamlet. The three proceed in the direction of the town but as they approach, the villagers observe them off in the distance. With trepidation, the villagers immediately began scurrying about, hiding their stores of food and supplies as “Soldiers are always hungry…”

Upon entering the village, the soldiers are met by “poor” peasants who bemoan to the soldiers that they are starving and have nothing to spare for three hungry men. Suspecting that the villagers may be embellishing the meagerness of their resources, the soldiers devise a clever plan.

Thinking outside the box, the soldiers contrive a strategy to get the peasants to give up their precious stores. Since there is no food available, the soldiers declare to the villagers that they will make “soup out of large stones,” if of course, the villagers can spare any…

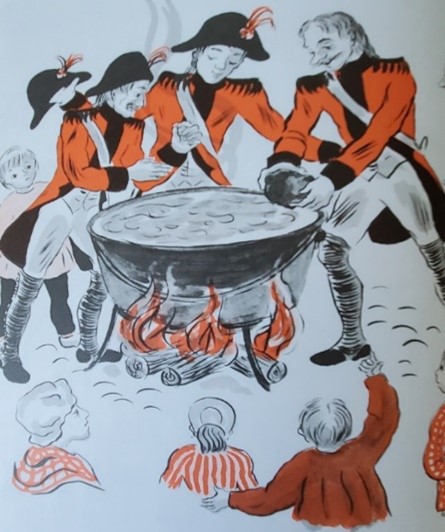

Intrigued by this revelation, the villagers all gather to observe this miraculous transformation of stones into soup. Now appearing to be rather simple folk, of somewhat superstitious dispositions, they are easily persuaded that soup from stones is not only plausible but also is a delicious possibility. As the villagers watch the soldiers in action, one soldier casually comments that this soup would be fit for a king if it only had some carrots. A curious and unsuspecting peasant claims he might have a few to spare and goes off the gather them. As the carrots are added, the soldiers continuing to proclaim how much better this “stone soup” would be if only they only had, meat, potatoes, etc.

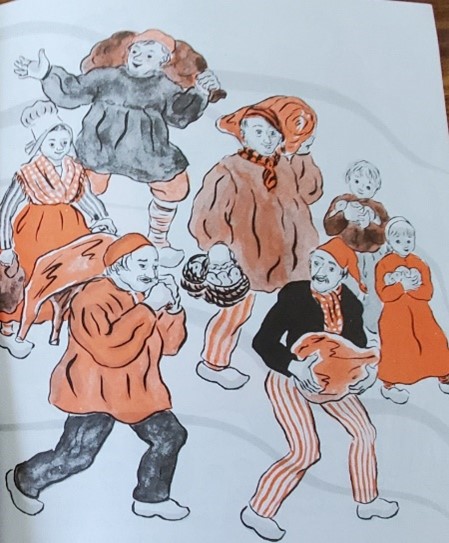

As the story goes, the townspeople, slowly but surely bring forth the various ingredients, adding to the richness of the soup. Once all have been added, the soldiers declare that the soup is finally complete and ready to serve. The peasants and the soldiers gather to sample the soup. As the stew is now rich and savory, all are pleased and additional food and drink emerge, tables are set, and a feast is had by all. Soon thereafter, the soldiers are dancing and singing with the villagers, celebrating into the wee hours of the morning. Later that night, exhausted by their revelry, the villagers and soldiers retire, the soldiers being offered the best guest accommodations in the village.

At the end of the tale, the villagers thank the soldiers for their genius, and the soldiers, in turn, thank the townspeople for their hospitality, all parting with smiles and best wishes.

Now some may think, this is a silly tale with little relevance to today’s Special Operations. At closer examination, however, there are perhaps some “pearls of wisdom” that can be extracted. Lessons that one could agree are equally relevant to working “by, with, and through partner forces” when dealing with people in general, especially those in a foreign country. For those experienced in living and working abroad, these nuggets are nothing profound, but to those uninitiated in cross-cultural engagement, these teachings may come in handy, especially should you find yourself in a far-off land with nothing but stones to eat. Here are some key takeaways to consider…

“Understand the Operational Environment.”

Special Operations Forces (SOF) imperative number one, Understand the Operational Environment, arguably holds that first spot in the hierarchy of SOF imperatives because it is the most important factor in any operation. The soldiers in Stone Soup recognized that understanding the operational environment was paramount to success. In a far-off land, with little provisions, untrusted and outnumbered by a potentially hostile populace, the soldiers in Stone Soup had to assess the operational environment, understand the human terrain and develop a sense of situational awareness.

Understanding one’s operational environment is a continuous process that requires near relentless analysis. The word “understanding” is both a noun and an adjective. As a noun, understanding is the ability to recognize something, it is comprehension. Equally so, understanding is an adjective that means sympathetically aware of other people’s feelings; tolerant and forgiving, and having insight or good judgment. Indeed, that understanding starts long before the operation begins, as aspects of culture, language, history, ethnicity, tribal affiliation are just a few of the many factors requiring attention. Failing to understand the nuances of your operational environment can jeopardize the success of the mission.

“Niceness counts.”

Not all doors need to be kicked in to get them open, sometimes you need only knock. As the soldiers in Stone Soup quickly ascertained, courtesy and respectfulness are virtues to be cultivated and employed when needed. A Special Forces Team Sergeant I knew had a mantra that he often quoted when working alongside allied counterparts. “Niceness counts” he would say. It was a sentiment that I did not fully understand or appreciate until much later in my career when I found myself working extensively with foreigners. He was referring specifically to showing appreciation for those who you seek to co-op into fighting for your cause. Treating the indigenous personnel and partner forces with respect, politeness and professionalism go a long way in winning the “hearts and minds” of those you seek to recruit and lead. Sometimes we are averse to understanding people and cultures that are different. That can lead to misinterpretation and even disdain. Treating others with fairness, dignity, and respect are universal behaviors that transcend all societies, traditions, and ethnicities. Niceness counts, especially when making soup from stones.

“You can’t surge trust.”

Although the villagers of the story seem naïve and gullible, my sense is that they were anything but guileless. As they encountered the soldiers, their natural reaction was to be wary, to be untrusting and guarded, until they could assess the intent of the soldiers. Trust is something that cannot be established without patience and effort. The soldier’s ploy to convert stones into soup was less of a ruse and more of a demonstration. That in this imaginative caper, the soldiers proved that they meant no harm, they were pure in intent and through their actions, enticed the villagers to play along. The villagers were no idiots, many soldiers had probably passed back and forth across their paths. The country dwellers saw that these soldiers were intelligent, ingenious, and meant no malice (at least for the time being) and assessed that they could be trusted. Once rapport and trust were established, the bonding between the two groups commenced.

“Think critically, act creatively.”

When faced with the situation in which the villagers declared that they too were hungry and without supplies, the soldiers had several courses of action available to them. Many of those more conventional approaches would have perhaps obtained the desired outcome, but there may have been unforeseen second and third order of effects. Develop Multiple Options and Apply Capabilities Indirectly are SOF imperatives that certainly came into play in the calculus of the soldiers in Stone Soup. Approach to complex problems requires a model of thinking that involves examination from a comprehensive optic. A 360-degree “walk-around” of the problem gives perspective, insight, and detachment from biases that might otherwise cloud or predetermine a course of action. The soldiers discussed and reviewed the “merits of the adversaries’ cause” before deciding which approach to take. They anticipated the psychological effects of a more direct or forceful approach of taking the food directly from the villagers and opted for a more surreptitious, but ultimately, more creative and effective plan.

“Act like the natives, but don’t go native.”

Respect for another’s culture, traditions, customs, and language are elements that lead to the building of trust and rapport. Showing deference to one’s “ways,” participating, and showing a genuine interest in how others conduct their lives are important to understanding and acceptance. The soldiers interacted at the human level with the villagers, not in the established order of their roles, but as human beings. They danced and sang in accordance with the traditions of their hosts. They were polite, considerate, and authentic. This endeared them to the townspeople who offered up the best of accommodations for them at the end of the day. The temptation to “extend the hospitality” of the villagers a few more days, or perhaps even weeks, was certainly inviting for the soldiers. For the townspeople, having a few strong soldiers to help care for the village, perhaps even protect it from other soldiers with less noble intent, was an enticing possibility. But the soldiers recognized that they could not become too comfortable, complacent, or enamored with the natives. Familiarity, it is said, breeds contempt, so the following day, they said their goodbyes and proceeded on their mission to return to their own homeland.

“All give way together.”

“All give way together” is a boat command used to ensure everyone on the crew of a rubber raiding craft paddles together in unison. Without the collective effort of those paddling, the boat can make little forward progress and can be swamped by the surf. One of the key takeaways from Stone Soup is that collectively, we can accomplish much more when united and “give way together.” Without the imagination, resources, and cooperative attitude of the group, “stone soup” would have amounted to nothing more than a slurry of dirty, hot water. The soldiers in Stone Soup were able to rally the villagers around an idea. Embracing that idea, the villagers enriched it with their assets and spirit. Working together, miraculous things can happen.

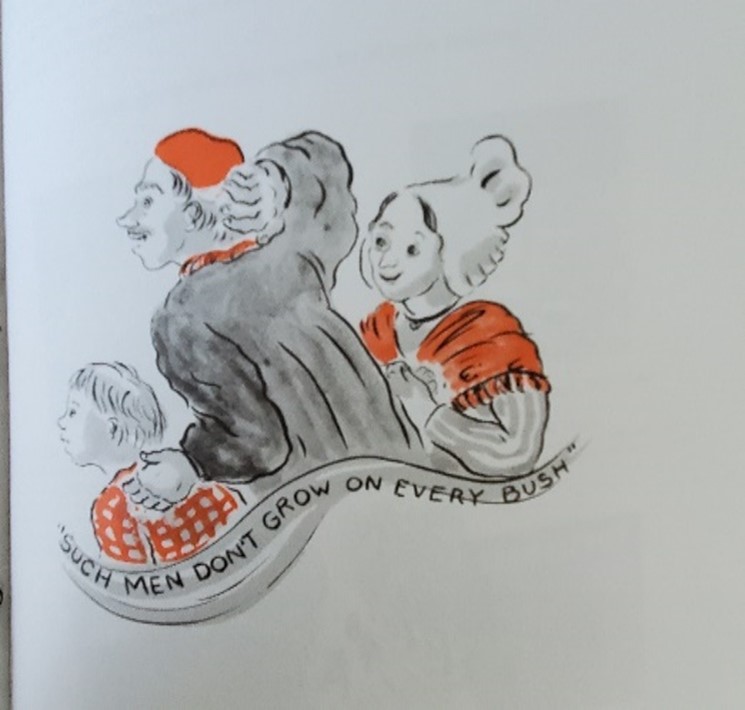

“Such men and women don’t grow on every bush.”

For the past two decades, Special Forces have honed their Direct-Action skills on the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan. As the U.S. Military shifts focus toward meeting the challenges of our adversaries in the “Great Power” competition, Special Forces will once again find itself on the forefront, gravitating back to its roots of working with indigenous forces and allies. Missions such as Unconventional Warfare, Foreign Internal Defense, and Security Force Assistance will likely assume the pole positions within the Special Forces mission requirements. The skills required to effectively train, advise, and assist our partners and allies require dedicated development and careful consideration. Stone Soup is plentiful in helpful ingredients in that regard. It merits a read and thoughtful contemplation for all those who seek to be better Special Forces soldiers and better people.

This first appeared in The Havok Journal on August 12, 2021.

The author is a former Special Forces officer who served as a Military Attaché and was stationed in four U.S. Embassies. After retiring from the Army, he joined the Defense Intelligence Agency as an Intelligence Officer and later served at the Joint Military Attaché School. His operational experience includes duty in Latin America, the Balkans, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2024 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.