A Chinese surveillance balloon has dominated everyone’s news feeds for the last several days, but there is more to this story than is being reported. The Chinese intelligence collection apparatus is far more expansive and insidious than a flagrant violation of U.S. airspace, and it is more than likely that the balloon was doing more than just taking pictures. This article will discuss what information that surveillance balloon was likely compiling and the size and scope of the Chinese Ministry of State Security’s (MSS) intelligence networks.

The All-Seeing Dirigible

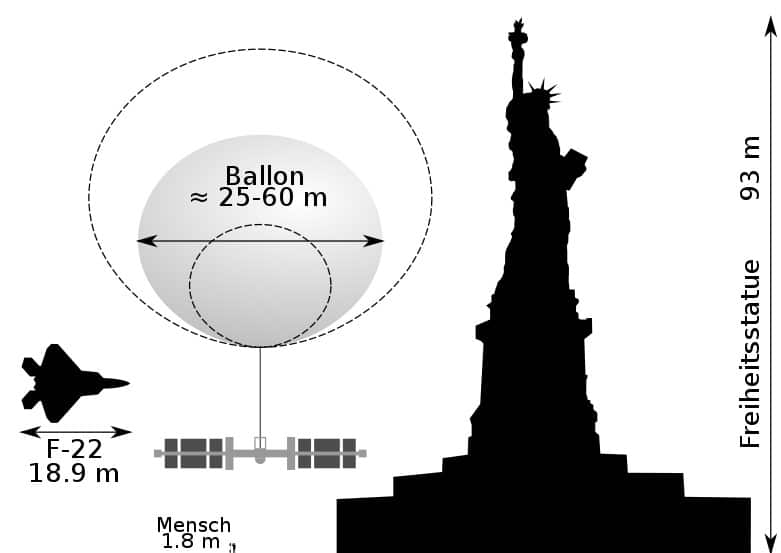

The size of the balloon’s collection platform and the altitude it was traveling could indicate that it was collecting more than just high-resolution images. During its travels, the balloon also likely gathered MASINT (Measurements and Signature Intelligence) and SIGINT (Signals Intelligence). MASINT examines things such as soil and material composition and density, acoustics, seismic data, CBRN (chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear) signatures, and spectrographic (varying light spectrums) information. SIGINT identifies and analyzes electronic signatures such as communications, radar, and electromagnetic emissions.

The collection of MASINT and SIGINT of and around sensitive military sites, like nuclear missile silos, would allow that adversary to understand better its defenses and capabilities and how to detect and identify more clandestine locations with similar signatures. This information provides a rival or hostile actor with significantly increased first-strike capabilities. For example, using synthetic aperture radar and other MASINT, the Chinese could see the material composition and strength of a missile complex, how deep it went, and environmental conditions they could exploit to destroy or disable the silo. Similarly, the Chinese could use the MASINT and SIGINT from these sites, like nuclear or electromagnetic emission signatures, to find other sites that remain undetected through other means.

The MASINT theory gains traction with reports of other Chinese surveillance balloons spotted worldwide traversing seemingly strategically insignificant areas. However, there is value to China in this data. For example, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) uses unscrupulous financial practices in developing countries to gain strategic holdings and acquire lucrative land holdings, like mineral deposits. MASINT from one of these balloons would allow the Chinese to narrow their focus on what states to manipulate and exploit and where to purchase or leverage land. BRI or land deals were likely not the primary MASINT mission of the U.S. balloon overflight. Still, as the next section will discuss, the Chinese have a penchant for amassing data, even if it is not immediately relevant or valuable.

Every Citizen is a Sensor

An analogy within the intelligence industry compares the differing collection strategies of the U.S., Russia, and China using a beach as an example. If the Russians want to know about a beach, they send in a Spetznas team, and they each grab a bucket of sand and speed away. The Americans will use satellites and drones to take a million pictures and MASINT to learn everything they can about the beach. China will send millions of its citizens to bring home a single grain of sand each.

That Chinese portion of that analogy could not be more accurate. A colleague who is an expert on China once stated that Chinese citizens must meet with an MSS representative for an “assignment” to have their permits to travel abroad expedited or even approved by the state government. These assignments are usually passive collection methods but often include more active HUMINT (Human Intelligence) and IMINT (Image Intelligence) collection. The passive collection method is gathering information incidentally, like overhearing a conversation or coming across NOFORN (no foreigners) sensitive content on a forum during a web search query. The active collection methodology involves purposefully seeking specific information about a particular subject, like eliciting information about an electronic component design or exploitable closed-door discussions.

Trade shows, conferences, academia, and business interactions are significant sources China collects HUMINT, ranging from sensitive military data to intellectual property and proprietary information. For example, hundreds of Chinese nationals attended the Shooting, Hunting, and Outdoor Trade (SHOT) Show, a significant gathering for the firearms, defense, and law enforcement industries. Several Chinese companies had vendor booths at that convention displaying products, mostly cheap knock-offs of American or European wares and likely stolen designs.

However, most Chinese attendees were spectators visiting the various displays, taking numerous photos and videos of the exhibited products and other visitors. Similarly, the Chinese representatives engaged in a passive collection of discussions and more active elicitation of naïve vendors and other attendees. This kind of HUMINT activity is pervasive across numerous industry conventions like the CES (Consumer Electronics Show), providing unique access to proprietary information, intellectual property, and dual-use (military and civilian applications) technology.

These trade shows and conferences also present the opportunity for Chinese intelligence officers and proxies to recruit intelligence assets; however, these practices are even more prolific and subtle within academia. MSS officers and surrogates identify and recruit pliable or exploitable individuals that may not be immediately useful. Still, they can utilize these individuals as future assets as part of a long-term goal. These goals can range from sympathetic voices in business, media, or politics that will parrot China-positive narratives to cultivated insider threats with various U.S. industries. The ultimate strategy in this widescale HUMINT collection effort is to give China economic, diplomatic, and military advantages against its rivals and competitors.

Conclusion

The recovery of the downed balloon will undoubtedly provide more information about what was collected and the implications of China having that information. In addition, the geopolitical ramifications between China and the U.S. add to this situation’s complexity and foreign policy challenges. However, the short-term fixation on one balloon should not overshadow the massive Chinese HUMINT espionage program that has already cost the U.S. hundreds of billions in economic losses or presents an exponentially increasing national security threat.

Ben Varlese is a former U.S. Army Mountain Infantry Platoon Sergeant and served in domestic and overseas roles from 2001-2018, including, from 2003-2005, as a sniper section leader. Besides his military service, Ben worked on the U.S. Ambassador to Iraq’s protective security detail in various roles, and since 2018, he has also provided security consulting services for public and private sectors, including tactical training, physical and information security, executive protection, protective intelligence, risk management, insider threat mitigation, and anti-terrorism. He earned a B.A. and an M.A. in Intelligence Studies from American Military University, a graduate certificate in Cyber Security from Colorado State University, and is currently in his second year of AMU’s Doctorate of Global Security program.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2024 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.