by Lana Duffy

Last night I sat having a beer or two with some good friends who happen to be fellow veterans. As it sometimes does, the conversation turned to mental health and our experiences.

I haven’t been back to a counselor since the last one told me I looked like his wife and started speaking to me in Italian. I’m not Italian, nor do I speak it. If you can believe it, the conversation got weirder from there.

The one before him repeatedly asked me to tell him about the worst day I had in my deployments. I told him no, I’d rather not, since I prefer not to think about that day or many of the others, and he told me about his worst day at the office. I left halfway through his story.

A few years later, a close friend suggested I put some things on paper, share what I’d like to share. After some gentle and not-so-gentle needling, I did so. It started to help. I shared a few more things. It helped a little more. A few things got me into trouble. It felt like old times. So today, on what is often one of the hardest days of the year for me, I thought I’d get some writing done.

On 8 July 2005 it was the third day of a massive cordon and search operation during which multiple organizations were hunting for over a dozen individuals in central Iraq, and as a part of the ground intelligence force I was helping to lead the charge. We’d been on the ground for 17 hours a day, walked through irrigation canals full of human feces, and stared down the 130 degree sun. We’d conducted operations dismounted on the first day, and on the second and third picked up vehicles. We raided homes and found the bad guys with the bombs. That was our job.

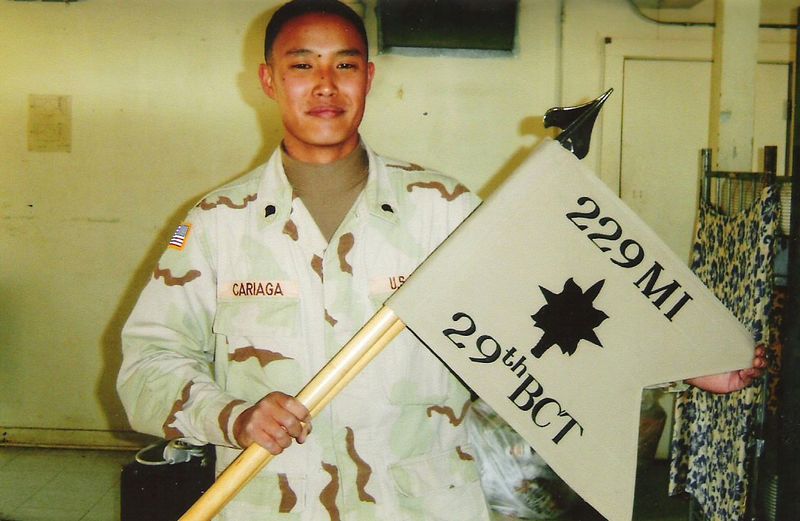

The day before I’d walked the dirt streets of al Shihabi with Deyson (Dice) Cariaga, a relatively new soldier who was training to become an intelligence collector. As we wandered from house to house with our infantry escort, we talked about his time at home in Hawaii, what I’d done in college and why I enlisted anyway, and a lot about the job. Despite the constant smell of dirt and sewage, the oppressive heat and the weight on our backs, one thing was clear: we both loved the job. There was something exhilarating about pulling the worst of two societies off the streets, figuring out the puzzle of which question to ask and how to get this done. Dice said to me at the end of the day that he could spend the rest of his life doing this and it was what he was meant to do. We got back in our vehicles, both of us driving our teams, and headed back for a few hours of sleep.

The next day was my promotion board, so I’d miss the final day of the operation. I’d tried to argue it, since we were scheduled to have a short operational day and I could come right after, but my team leader pulled our team from the manifest. With our vehicle off the line, Dice hopped in the driver’s seat of a 998 with add-on armor and pulled forward.

They got done early, as we’d suspected, and right around 1pm when I was answering questions on vehicle maintenance and weapons to a small band of first sergeants, they pulled away from the last road of the village. While I sat waiting on my score, they drove past al Hammadi. While I got word I was going to be added to the list after acing the board, Dice’s front left tire hit a pressure plate in the road and set off a round packed with white phosphorous, engulfing his truck in flames and killing him instantly. The other three occupants made it out; there was almost nothing left of Dice to identify. As I left the small room where we’d held the board with my proud team leader, I was grabbed by a warrant officer and asked to help my unit determine which of the other team members had been killed on the mission I’d missed.

I can remember the smell of the other team’s office, the map peeling from the walls in the heat, and the dead looks of his teammates as his team leader hugged me desperately. And all I can do to reconcile the memory of my command noting that my truck, my seat, was supposed to be occupying that space that day is to wear a metal bracelet bearing his name. Nine years later I sit typing on a deck with that bracelet scratching the edge of my laptop. And I can write about it, at least, but it still drains me to put a voice to the words.

And was that the worst day in Iraq? Not even. It was a horrible, horrible day, but there were worse. There are days I haven’t talked about, days that wake me up from a dead sleep with images and faces that I don’t think I can lie on a couch and simply talk away to a stranger. These are days I don’t even discuss with my friends, not even those who were there. I had a massive brain injury courtesy of an IED a few months after Dice was killed. I sometimes can’t even remember what I had for breakfast or what word describes that particular thing I know I’m forgetting, but I remember the hell out of each of those days.

But as I sat talking to my friends last night, it occurred to me that a year ago I couldn’t even tell Dice’s story, not even in writing. It still makes me uncomfortable; I still feel the guilt. But I realized that now I can tell the story and a little bit of the weight is lifted. I can admit that as an intelligence collector you feel the pain of every explosion, every casualty in your area, because you didn’t find the bomb or the bomb maker first. I can start looking to the root of my temper, to my three hours of sleep at night, to my impatience, and begin to understand how I can work to change it.

I still haven’t decided if I’m ready to go back to therapy, if I’m ready to really confront a lot of things, but the benefits are real. Writing it down is real. Talking about it is real. Finding a complete stranger to listen is real. And whatever is real to each of us, we need to do it.

We can’t be here to help future veterans if we aren’t dealing with our own experiences, so we need to find what is best for us to confront our demons and move forward. I wallowed for years, just now starting to dig my way out. I have no idea what opportunities I’ve lost, what I’ve given up in favor of trying to protect myself from thinking.

I miss you, Dice, just as I miss Frank and Mike and all the others. That won’t change, nor should it. But I will, and I’m looking forward to it.

This article originally appeared in Ranger Up’s Rhino Den.

__________________

This first appeared in The Havok Journal on July 9, 2014.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2024 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.