In a recent post on Facebook I asked my fellow veterans to respond to the prompt, “What Is A ‘Deployment,’ Anyway?” In their responses several of my colleagues, both publicly and in private, invoked one of the many elephants in the Veteran Community room: what about veterans who never deployed to war. I thought that was actually a far more interesting topic than an analysis of the semantics about what constitutes a military deployment and what doesn’t –don’t worry, we’ll get there in a later article–so I chose to write this piece first. If you’re wondering what my own experiences with war are and what qualifies me to opine on this topic, you can find a short bio here and determine for yourself whether or not my thoughts on this subject have any validity.

The inspiration for this article came from a message I received a few days ago from a former cadet with whom I worked at West Point. He was, and is, a high achiever and good man who joined the Army seeking his chance lead in war but after several years has not yet found it. He, like so many others who came into the Army via West Point, or from my own alma mater Georgia Military College, or who enlisted in their own hometown, joined to do their duty. And make no mistake: ultimately, our duty is war. In his message he expressed concern that his opportunity had not yet materialized, and no small amount of disappointment in realizing that it may indeed never come.

I understand that sentiment, because I once felt that way too. This is message for him, and for the hundreds of thousands of US military veterans who, for legitimate reasons outside of their control, never went to war during their military service.

Yes; of COURSE it’s ok that you didn’t go to war.

As you will see below, I have a lot to say on this topic. And in what is perhaps typical “officer” fashion, it takes me a long time to say it. So for those who are already thinking “TL;DR,” I offer the below summary, from a friend of mine who I’ll just call “A Jaded Former SF Guy,” who spent a lot of time in Army Special Forces and completed several combat tours himself. As one would expect from someone with his pedigree, he cuts through the BS with clarity, brevity, profanity, a whole bunch of acronyms, and a few inside jokes, and he gets straight to the point, which is this: Yes; of COURSE it’s ok that you didn’t go to war.

Yes; it’s ok that you didn’t go to war.

It’s also ok that you didn’t go to BUDS

…or Ranger school

…or the SFQC

…or airborne school

…or that you weren’t an 11BIts OK that you weren’t a Recon Marine,

…or a PJ

…or a fighter pilot

…or a Submarine Commander that didn’t film porn on the boat while living under the seaIt’s ok that you never made it past E4.

It’s ok that you never pinned on a Star.

It’s ok that your ETS or retirement award wasn’t an LOM

…or a Meritorious Service Medal

…or an ARCOMIt’s ok that you spent 4 years as a cook, or a mechanic, or a supply specialist, or a mail clerk in the lamest most obscure support unit in the most isolated obscure post in the USA.

An armed force cannot operate without EVERYONE pulling their weight.

… whatever that weight may beBe proud of that shit – whatever you did – it was important – it helped move the machine along.

While you were going to basic training, most of your mother fucking peer group was going to the mall.

Of COURSE it’s ok that you didn’t go to war…

… just don’t fucking lie about it.

A question of legitimacy…

There’s a lot to unpack in the above quote. But I first want to revisit something I mention in the opening paragraphs of this article, that being the caveat about “legitimate reasons” for members of the military not going to war.

There are any number of legitimate reasons why someone in the military might never end up in a war zone. For example, they might serve in a rare period of time when American wars are small, or scarce. If someone did an enlistment in the mid-1990s, for example, it is likely that they would have never experienced an overseas war, especially if they only spent a short time in uniform. Or they may have a specialty that is essential for the overall function of their service, but is almost exclusively a stateside assignment. Certain medical functions or space warfare specialties may fall into this category.

No matter how long you spent in the military, and no matter your job, it’s also legitimate if you sincerely tried to go war and never did. Especially these days, combat deployments are hard to come by. I’m shocked by the number of young officers and mid-grade NCOs who come to work at West Point with zero combat experience. But it’s not their fault, and is no reflection on their worth to the unit. Even back in the day, during the time when some troops seemed to be going every other year–or even more frequently–sometimes a “deployment” didn’t get you to the “war.” For example, my best friend and the editor of The Havok Journal, Mike Warnock, volunteered for a hush-hush mission that involved overseas deployment and even a formal non-disclosure agreement… only to find out too late that it an assignment to–wait for it–Guam.

Guam.

Is that a deployment? Well, technically, yes (stand by for my upcoming article explaining why). But it wasn’t war. Not the way most vets see it. Mike was gutted when he found out where he was going, and he talks about it in the extraordinary article he wrote for Havok Journal, “Lost Without a Tribe”. But Guam was where his country needed him, so that’s where he went, because that’s what duty required. Now the epilogue on this vignette is that because he stayed in for 20 years Mike did end up subsequently going to Iraq twice, but many folks don’t get that chance. I can only imagine what Mike would feel like if he did 20 years during almost the entirety of the GWOT and “all he got to do” was Guam. It’s always fraught to invoke a figure as controversial as Robert E. Lee (and I thought the quote came from George Washington), but he once said something abut duty that I think applies to every service member, ever. I also think it’s appropriate both in Mike’s case and in the broader discussion we are having here:

Duty is the sublimest word in the language; you can never do more than your duty; you shall never wish to do less. –Robert E. Lee

Keep the above thought in mind, because we are going to revisit it later.

I also think it’s completely legitimate if a service member prioritizes family over the military, if the choice is one over the other. I recognize that this sentiment may be controversial but I am entirely comfortable saying it and I stand by it: family first. Family first, last, and always. Yes we join to serve the nation, but the most important element of the nation is its people, and the most important organizational element of people is the family. I used to tell my cadets, and anyone else who would listen, “No matter how good you are as a Soldier, no matter what you do and how much you give, one day you will leave the Army or the Army will leave you. But if you do it right, your family never will.” If at any point in my career it would have come down to either my family or my Army career… well that’s an easy choice for me to make. So if someone left the military before they could deploy because they were dual military, or a single parent, or had a sick or injured family member that they needed to take care of, I’m OK with that. More than that, I salute it.

A service member might also be non-deployable for reasons beyond their control. I’m not talking “you skipped your last checkup so you’re red on Dental” nondeployable. I mean things like development of conditions that would endanger themselves or degrade the unit if that person went downrange. While I think there is an argument to be made that those types of people shouldn’t be allowed to remain in the Army in the first place, that ship has kind of sailed. And there are plenty of things that people can do to support the wars while they are still here and in uniform in the US.

I also think that if your priorities, or your capabilities, or your conscience preclude you from going to war in the long term, or if anything in your mind or in your heart prevents you from giving it your all, it’s time to go. I left the Army when I did because of the way Afghanistan ended, as I no longer thought I could, in good conscience, continue to be the kind of officer I needed to be while holding the kind of things I was holding in my heart about that debacle. So if officers decided that their moral compass would not allow them to point themselves to war, then the rest of us who did go were probably better off without them.

But at the same time there are also plenty of illegitimate reasons for not going, such as cowardice or toxic self-interest. I have seen deployment dodgers in far too many of the units I served in over the years. They do exist, and there definitely a conversation that we need to have about that. But this is not that article. If people fake injuries, or inflict injures or conditions (such as pregnancy) on themselves specifically to get out of a deployment, then yeah I don’t see that as legit. And I usually find it suspect when puts their personal ambitions over the needs of the unit, or their troops.

Some (many?) veterans will disagree with some or all of the above, and that’s OK too. They’ll say things like, “wait, isn’t literally everything you listed above some kind of self-interest?” and they’ll be right. But to me there is a difference between self-interest (which I see as legitimate motivator) and selfish interest, which is toxic and inconsistent with military ethos. I recognize it’s subjective, and that reasonable people will disagree.

A little bit of background and context…

When I was young, I, like most young men in the Infantry, longed to go to war. I hoped for my chance when I led a platoon of the 101st Airborne Division in the Multinational Force and Observers mission in Sinai, Egypt in the late 1990s. But the war never came, even though we drew “hostile fire pay” for the months when our duties took us into the Red Sea. I hoped for war again when I commanded a military intelligence company in the Second Infantry Division (2ID) in the Republic of Korea (ROK), and while North Korea and South Korea never officially ended the war between them, it sure didn’t feel like there was a war going on during the two years I was there. More importantly, there was no awarding of the coveted “combat patch,” which is authorization to wear a unit patch on the right shoulder instead of just the left. Perhaps more than anything else in the Army, that right shoulder patch is the ultimate symbol of whether or not someone went to war (some exceptions apply; in some conditions a right shoulder patch is not indicative of wartime service). No matter what unit patch it is, just having one imparts some level of “been there, done that” credibility to the wearer. Like the former cadet I mentioned at the start of this article, I desperately wanted one of my own.

I was stationed at 2ID’s Camp Essayons in the town of Uijongbu, ROK when 9/11 happened. In the uncertainty that followed, I kept my soldiers busy by digging fighting positions and executing reaction drills for a North Korean invasion that our higher headquarters repeatedly warned us was coming, yet thankfully never materialized.

When September stretched into October and the US eventually went in on the ground, I was certain that the war would be over before I left Korea. I took command before going to the Officer Advanced Course (OAC), a primary purpose of which was to prepare officers for company-level command. I tried to skip the course and head straight to Afghanistan, but as I had gone to the Infantry basic course and knew very little about operational and strategic level intelligence, MI Branch made me go to MIOAC (Military Intelligence Officer Advanced Course)… which was absolutely the right call. While I was in the course, a call for volunteers went out. If you were selected, you would gradate MIOAC early and head downrange.

I was not selected.

When I returned from CASSS (the Combined Arms and Services Staff School, which I think no longer exists), our branch representatives came to Fort Huachuca for the purpose of assigning us to our post-course units. I did well enough in OAC but wasn’t burning it down academically. And since I had already 1) gone to Korea and 2) been a company commander, my branch manager let me pick where I wanted to go next. 5th Special Forces Group sounded sexy, and it was a unit my father had served in when he was a Green Beret (B/2/5). Plus it was only two hours away from where my parents lived. So that’s where I went.

When I got to Group in 2003, I was put in an unchallenging job and it appeared that I would not be deployed for a while. Concerned that the wars were going to end any day (lol!), I started exploring the process of leaving the unit and going over to the 101st. Fortunately for me, I suddenly found myself in command of the Group MI Detachment, and orders to Iraq. I got my chance to go to war. So did a lot of other folks in Group. Lots of folks ended up with combat patches. But probably not all of them deserved it.

While I was waiting to go to Iraq, my immediate headquarters, the Group Support Company (GSC), organized an advance party or ADVON to do a short trip to Iraq as part of setting the conditions for the deployment of the Group’s main body. I desperately wanted to go on on that ADVON, knowing that just because I was probably going to Iraq, didn’t mean that I was going. And I had to get that combat patch! But the GSC commander, a Special Forces Officer who was both older and wiser, refused to let me go because my wife was extremely pregnant with our first child. What a blessing. What a relief.

“Your time will come,” he told me, as I stood there in a mix of disappointment and relief. And he was right. Oh, how he was right.

Just because someone went to war, it doesn’t mean that they did a good job while they were there.

While going to war definitely means something, it doesn’t mean that someone did a good job there, or even that they’re a good person. It just means they were someone who went to war. That’s all. We can probably all think of examples of people who deployed to war, are war veterans in every sense of the word, but who also committed heinous and inexcusable crimes while they were there. We would have all been better off if they would have just stayed home.

Here’s another example from my personal experience. When I was an intelligence officer in the 5th Special Forces Group, we sent a piece of top secret (TS) equipment to Iraq to support the Group’s operations there. This was before my first deployment to Iraq in 2004, so the war there was still pretty new. TS equipment requires a two-person rule for security in transit so I, thinking myself a good and caring Military Intelligence Detachment commander, sent two soldiers whose re-enlistments were coming up. Re-enlisting in a combat zone meant their enlistment bonuses would be tax-free, and in a time were intel skills were in demand and the Army literally had to prevent people from leaving through a policy of “stop loss,” the bonuses were very big.

My detachment sergeant, a grizzled, knowledgeable and deeply experienced E8 who had already been to Iraq once with 5th Group, advised against sending one of the two individuals because, in my det sergeant’s words, “he’s a dirtbag.” While I agreed that the soldier in question could use some work, I didn’t think the problems with him were bad enough to deprive him of this opportunity. I also thought that this would help motivate him to be a better soldier (spoiler alert: it didn’t). And since my det sergeant didn’t seem to feel particularly strongly about it either way, I decided to send him.

The transport mission went fine, but over time I came to realize that my det sergeant was right. In fact, this particular individual was such a low performer that we decided to leave him behind on rear detachment when the rest of us deployed to Iraq in 2004. We would rather go short in a critical specialty in a literal war than risk the liability of having him with us.

Shortly before we got ready to leave for Iraq, this same soldier came down on orders to leave the unit. Good riddance. As he was doing his outprocessing, I noticed that he had started sporting our unit patch on both sides of his Army combat uniform. As previously mentioned, when worn on the right a unit patch is a combat patch, and indicates combat service with that unit. Whether you were a Green Beret or a support guy like me, having an SF combat patch imparted a lot of prestige and credibility, whether it was earned or not. Part of my calculus in not bringing this soldier with us to Iraq was because I did not want to afford him the honor of having a Special Operations Forces combat patch fand have him run around the rest of his career with that level of imparted credibility, telling young soldiers “when I was in Group…” stories.

I was actually glad to see him wearing that patch, because “general dirtbagness and assclownery” aren’t offenses under the Uniform Code of Military Justice. But falsely claiming combat credentials is, and now we had something to put down on paper. If it’s not written down, it didn’t happen, and I didn’t want this soldier (who had somehow managed to make it to the rank of sergeant) to go to his next unit and have them think he was actually a good guy. When I brought this up to my detachment sergeant he informed me there was nothing that we could do. “He earned it, sir,” he stated matter-of-factly.

My detachment sergeant, himself a war veteran long before I was, was known for being no-nonsense and having a steel trap of a mind when it came to Army regs. He also effortlessly memorized individual serial numbers for much of our sensitive military hardware, and when I would do inventories he could tell me, with a high degree of certainty, not only where that item was but who was signed for it just using the serial number. All based on memory. It was pretty impressive. So I asked him what he meant by “he earned it.” As far as I was concerned, the only thing this soldier had earned was a one-way ticket out of Group..

“Remember how you let him go to Iraq, and I told you it wasn’t a good idea? Yeah, about that…” he said. Now I was certain he was wrong about this. Our troop had only been in Iraq for like four days, and saw combat zero action. As was common practice at the time, we deliberately sent him at the end of one month and had him return at the beginning of the next month, so he would get the combat zone tax exclusion (CZTE) for two months. Back then, you only had to be in a designated hostile fire zone for one day out of month to get that benefit for the whole month, which was pretty significant money. He got that on top of having his re-enlistment bonus tax free. Fair enough, he spent some time downrange.

But I knew, just knew, even though I had never been to Iraq myself at that point, that he was wrong. It had to be 30 days. I looked up that reg and… surprise! (not really), my det sergeant was correct. Apparently, at least at that point in the war, one day was all it took to earn a combat patch. That was just further proof to me that while experience in war means something, it doesn’t mean everything. I’d rather have a good soldier who never went to war, than a dozen dirtbags who did.

There are different degrees of “war.” Individual experiences may vary.

“War” means a lot of different things for a lot of different people. The kinds of war my grandfathers experienced in WWII or my great-grandfathers in WWI were way different than what my father experienced in Panama and Desert Storm, or what I experienced in Iraq and Afghanistan. Experiences vary in the same theater of war, and even in the same operations. For example a drone operator might experience the war from an air conditioned trailer in Arizona while the drone he’s remotely piloting is blowing things up halfway around the world and then driving home to his own bed at night. In comparison, a Marine supporting that exact same mission might be kicking down doors and dodging IEDs and sleeping in the mud at night. Both of those missions have value. Both of those could be examples of doing your job in war.

War is not the same for everyone. For some additional perspective, I’ll use some further examples from my own career. My officer record brief (ORB), the detailed summary of my active duty military career, shows seven deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. I’m proud of that record. But context is also important. For the units I was in, at the times I was in them, seven deployments was kind of on the low end of average. Many members of the military had, and have, many more deployments than I do. For example, as I wrote about in an earlier article for The Havok Journal, US Army Ranger Kris Domeij had something on the order of 14 deployments when he was killed in action.

One of the main differences, though, between Kris’s deployments and mine were that his were on the tip of the spear and mine were more like… the shaft. Kris was an infantry noncommissioned officer in the Ranger Regiment. I was a military intelligence officer at units like JSOC. His job was outside the protection of the Forward Operating Base (FOB), mine was almost exclusively inside of it. I was a FOBbit, he was a Ranger. In all of my time in a war zone, I never once fired my weapon at another human being or killed anyone directly. For Kris, those kinds actions may have been pretty regular occurrences.

I don’t say that to try to downplay my own contributions. I’m proud of what I did. I don’t feel bad about how “non-kinetic” my own experiences were; after all, if the intel guys in the national-level SOF task force are having shootouts with bad guys on the FOB, it’s probably a bad day for everyone. I earned four bronze star medals and a combat action badge, among other things, for my time in Iraq and Afghanistan. But at the end of the day, all I did was my job, and that’s what we expect from every member of the military.

When I was in the war I went on just enough missions outside the wire to show the guys I was supporting that I wasn’t scared. It was a credibility thing, not a “I need more war” thing. And as I was fond of saying to my junior troops who were eager to go outside the wire and troll for gunfights, it’s hard for us to support the mission if we’re on the mission. Everyone has a job to do so get good at that. Sometimes doing your job well means you do it from somewhere other than the battlefield.

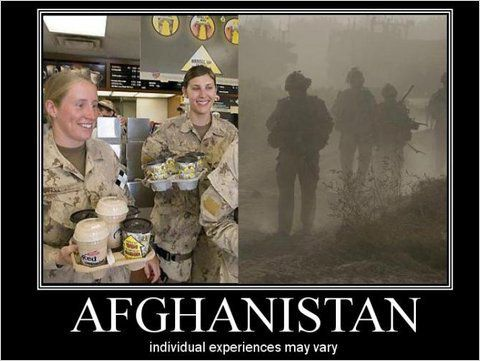

At some point during the Afghanistan war, a meme started going around showing the contrasting experiences of that war. On one side is a group of of what appear to be female Marines or Navy personnel smiling and carrying coffee out of what might be a Green Beans shop (yes, we had coffee shops on the big FOBs in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as Pizza Hut and Burger King). The right side of the meme appears to show an infantry squad patrolling in a dust storm.

The intent of the meme is to show the differences in some peoples’ wartime experiences. Of course, there is nothing to say that the people in the left side weren’t shortly thereafter the people on the right side, and vice-versa. But I’m using this as a point to illustrate that for some folks, their wartime experience simply a slightly-more-dangerous version of a trip to the National Training Center. At the big base in Bagram, Afghanistan there was a Morale, Welfare and Recreation (MWR) building just outside the SOF Task Force compound, where the conventional troops would have a weekly Salsa Night. The dining facility (DFAC) where we ate was adjacent to the MWR building, and we’d smell perfume and hear loud music and see men and women in “clubbing” attire going into and out of the building as we downed chow and got ready for that night’s mission. On a trip to a DFAC in Mosul, Iraq I saw a flyer on a table for a “Pajama Jammie Jam” on the base. I’m not making this up.

Sometimes, “war” isn’t all what it’s cracked up to be. As the meme says, your experience may vary.

It’s OK you never went, but…

I’m never going to tell anyone that going to war doesn’t matter. If you served in the military, it absolutely does. Not only is wartime service important, some might argue that it is the most important thing that a military does. After all, the duty of the US Army is to “deploy, fight, and win decisively.” But it’s only the most important thing that a military does, not necessarily the only important thing.

When I was in the Joint Special Operations Command, our commanding general, then-LTG Stanley McChrystal, was known for saying words to the effect of, “Don’t judge your value to the unit by your proximity to the battlefield” (sorry, sir, if I misquoted you a bit). That’s something I’ve always kept in mind, and tried to impart to my cadets and my soldiers. Do your duty. Do your job. It doesn’t matter if it’s on the front lines, or at the front of the customer service line in the finance office back at home station.

But at the same time, it’s also important to not act like war isn’t important, that it’s not the most important thing our military does. And it’s never OK for you say, or even imply, that you served in a war if you didn’t. That is a cardinal sin among veterans; in fact short of something outright criminal like treason or sexual assault, it’s one of the worst things a veteran can be accused of doing. So to paraphrase the eloquence of the Special Forces friend I quoted at the beginning of this article, don’t try to make people think you’re a war veteran if you’re not.

The bottom line is…

At the end of the day it’s not up to me to absolve anyone of any guilt they may or may not feel for anything they did or didn’t do during their military service; that’s something that they will have to sort out for themselves. Nor do I pretend to speak for every veteran, a fact that the comments sections on Instagram and Facebook will doubtless show. But if you did your job, did it well, served honorably, and took care of your troops… then you did your duty.

You can never do more. You should never wish to do less.

Of COURSE it’s OK that you didn’t go to war.

This first appeared in The Havok Journal on August 19, 2024.

Charles Faint is a retired Army officer and the owner of The Havok Journal. This article is his personal perspective and is not representative of an official view of any other person or organization.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2026 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.