by Cristóbal S. Berry-Cabán

The Peanuts gang are lounging together beneath the shade of a large tree, enjoying the crisp November air. Linus, clutching his ever-present blanket, reminds the group that it’s Veterans Day. Charlie Brown, frowning in thought, wonders aloud if there might be parades to mark the occasion. Peppermint Patty, her sandals tapping against the roots, chimes in that there ought to be “something special” to honor the day. Just then, Snoopy appears in his World War I Flying Ace helmet, goggles gleaming and red scarf trailing. With great seriousness, he announces his own plan: to head over to Bill Mauldin’s house and “quaff a few root beers.”

For Charles Schulz, the creator of the Peanuts comic strip, honoring Veterans Day was more than a gesture—it was personal. As a World War II veteran, Schulz was drafted in 1943 and eventually commanded a light machine gun squad as a staff sergeant in the 20th Armored Division. During the final push through Germany and Austria, he helped free American prisoners of war and was part of the force that liberated the Dachau concentration camp. He began paying tribute to this chapter of his life—and the service of others—in 1969, creating nineteen commemorative Peanuts strips for the holiday.

Following the war, Schulz pursued various art, illustration, and comic-related jobs, eventually creating his first serialized strip, Li’l Folks, which later evolved into Peanuts in 1950. At first, Peanuts resembled other newspaper comics of its time, with a simple artistic style and humorous daily strips often centered around the main character, Charlie Brown, and his beloved pet beagle, Snoopy.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, New York World-Telegram & Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, photo by Roger Higgins (No known copyright restrictions).

Snoopy has a fondness for root beer and pizza and strongly dislikes cats, coconut candy, and the screechy noise balloons make when being squeezed. He also suffers from claustrophobia, which makes him steer clear of tall weeds and sometimes even his own doghouse. One of his favorite pastimes is reading Leo Tolstoy’s classic War and Peace—at a relaxed pace of “one word a day.”

According to Schulz, no character evolved more dramatically than Snoopy. He began his life in Peanuts as a typical beagle, walking on four legs and engaging in simple dog behaviors like barking and fetching. As the years went on, Snoopy’s personality and appearance changed, with his inner thoughts and actions becoming progressively more human-like.

Much to Charlie Brown’s dismay, Snoopy often retreats into a vivid fantasy world. He envisions himself in various heroic or sophisticated roles—from a skilled surgeon to a sharp, bow-tie-wearing attorney, or the ultra-cool saxophonist, Joe Cool. This behavior prompts one of Charlie Brown’s most famous lines, as he laments, “Why can’t I have a normal, ordinary dog like everyone else?”

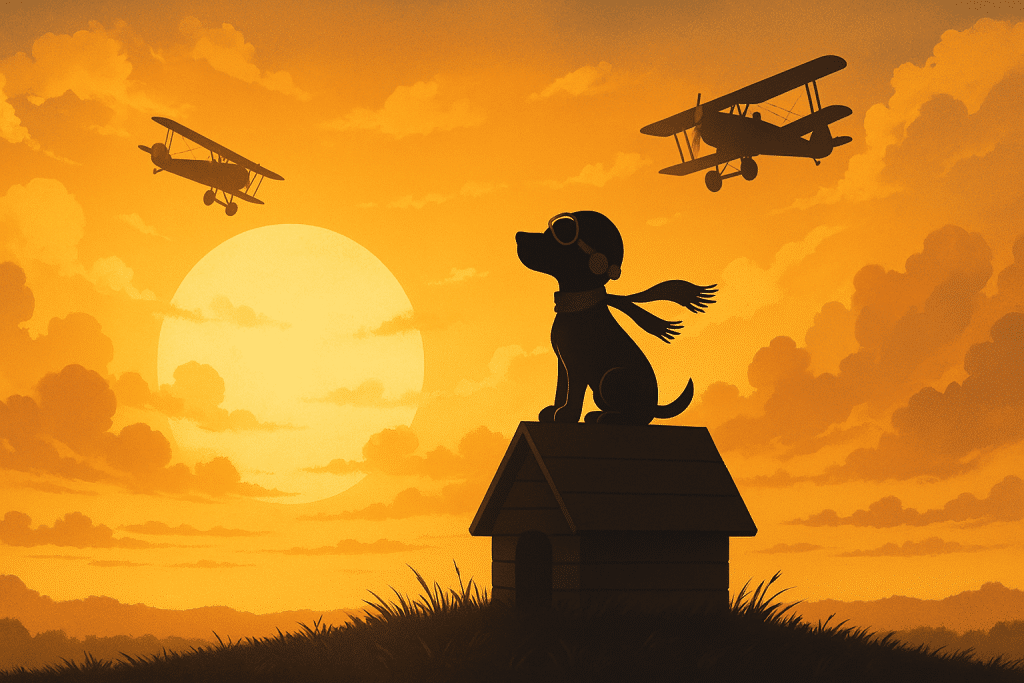

Of all Snoopy’s many disguises, none has captured the imagination quite like the World War I Flying Ace. Balancing on top of his doghouse—transformed into a “Sopwith Camel” fighter plane (Charles Schulz once chuckled, “Can you think of a funnier name for an airplane?”)—Snoopy takes to the skies to duel with his sworn enemy, the Red Baron, better known to history as Manfred von Richthofen. The Flying Ace first appeared in the Peanuts strip in October 1965, and ever since, readers have delighted in Snoopy’s daring missions, even though the Red Baron almost always managed to come out on top. The defeats usually ended with Snoopy shaking his fist at the sky and shouting his famous refrain: “Curse you, Red Baron!”

As the Flying Ace, Snoopy wasn’t just a pilot—he was a whole romantic vision of wartime adventure. In his imagination, he swooped through the clouds, stalked his foe across the Western Front, and touched down in Europe to sip root beers in rustic cafés or flirt with French mademoiselles. It was all make-believe, of course, but it was the kind of make-believe Schulz’s readers couldn’t resist.

The idea for the Flying Ace was sparked when Schulz saw his son’s World War I model airplanes and doodled a little flying helmet on Snoopy. That simple sketch soon grew into one of the most enduring parts of Peanuts, adding a touch of high-flying drama to the comic’s world of neighborhood baseball games and kite-eating trees. But behind the laughs, the Flying Ace also revealed Schulz’s own ties to the military. A veteran of World War II, he sometimes used his Veterans Day strips to connect Snoopy’s fantasy life to real soldiers and stories.

In those strips, Snoopy might be seen sharing a root beer—or several—with Bill Mauldin, the Pulitzer Prize–winning cartoonist and fellow veteran behind the legendary Willie and Joe war comics. Other cameos nodded to figures such as Ernie Pyle, the beloved war correspondent killed in 1945 during the Battle of Okinawa, and Audie Murphy, the most decorated U.S. soldier of the war who went on to star in movies and television. In one particularly cheeky moment, Snoopy even confided to Mauldin that he had once “met Captain Harry Truman in France.”

Snoopy’s Flying Ace shows how imagination can turn a simple beagle into a symbol of heroism and friendship. His make-believe doghouse battles with the Red Baron became some of the most celebrated moments in Peanuts, though creator Charles Schulz was uneasy with claims that they represented his best work. Over time, Schulz steered the Flying Ace away from wartime exploits and toward more personal struggles with love and loneliness at the front. As he later told biographer Rheta Grimsley Johnson in her 1988 book Good Grief, “It reached a point where war just didn’t seem funny.”

Snoopy’s imagined dogfights with the Red Baron inspired the 1966 hit “Snoopy vs. the Red Baron” by the Florida band The Royal Guardsmen. Written by Phil Gernhard and Dick Holler, the song climbed to No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100. But because the group had used Snoopy’s name without permission, Schulz and United Features Syndicate sued and won, claiming all publishing revenues. Still, Schulz later permitted the Guardsmen to record more Snoopy-themed tracks, including “The Return of the Red Baron,” “Snoopy’s Christmas,” “Snoopy for President,” and “The Smallest Astronaut.”

Like Schulz himself—and so many veterans of the Greatest Generation—the Flying Ace eventually had to reckon with life after the war. Schulz captured that reality in a Peanuts strip published on July 29, 1980. In the scene, Lucy and Marcie are perched on top of Snoopy’s iconic doghouse, while Snoopy, dressed once again in his leather cap and goggles, slips back into the persona of the Flying Ace. Lucy turns reflective, remarking, “I’ve heard that our captain was a fighter pilot during the war. I don’t suppose those experiences are easily forgotten.” Her words echo the lingering memories of real veterans, whose service continued to shape their lives long after the battles ended.

In the next panel, Snoopy abruptly breaks the silence with his familiar cry: “Curse you, Red Baron!” It’s a comic moment, yet it underscores a deeper truth—the past cannot simply be set aside. Marcie, ever the quiet observer, responds, “No, I guess not.” With that simple exchange, Schulz wove together humor, memory, and the enduring weight of wartime experience. The strip not only reflects Snoopy’s playful flights of imagination but also speaks to the lasting imprint of war on those who lived through it, blending lighthearted fantasy with a poignant nod to reality.

World War I, known as “The Great War,” formally ended with the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919. But the fighting had already stopped months earlier when an armistice took effect at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918—a moment long remembered as the end of “the war to end all wars.” Today, Veterans Day continues to be observed on November 11, regardless of the day of the week, preserving its historical meaning and honoring the service, sacrifice, and patriotism of America’s veterans.

Veterans Day holds special meaning in Peanuts, shaped by Charles Schulz’s own World War II service and his lifelong respect for those who served. Though he and fellow cartoonist Bill Mauldin never shared the “root beers” Snoopy once imagined, Schulz did meet him at a comic convention. When Mauldin asked why he included so many Veterans Day salutes, Schulz explained that he had admired Mauldin’s work as a young GI. Mauldin simply smiled and replied, “That’s all you had to say.”

Over time, Snoopy’s Flying Ace has become a fixture of popular culture, often featured in Veterans Day parades, ceremonies, and tributes. Even organizations like the American Legion have embraced Snoopy’s imagery to honor veterans. The Flying Ace adds humor and nostalgia to the Peanuts legacy while offering a lighthearted yet respectful nod to military service.

The enduring saga of Snoopy and the Red Baron reminds us of the power of imagination to keep history alive. Through Schulz’s work, Peanuts continues to honor the bravery and sacrifice of veterans, ensuring that the legacy of the Great War—and the spirit of all who have served—remains part of our collective memory.

__________________________

Cristóbal S. Berry-Cabán, PhD, a semi-retired epidemiologist, worked at Womack Army Medical Center, Fort Bragg, and lives in Southern Pines with his cats Solo and Biscuit, who enjoy sleeping in his home office. He has published extensively on military health. He can be reached at cbcaban@gmail.com.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2025 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.