There’s an old saying in risk management and public safety circles that I think all of us can relate to: “Everyone likes firefighters. No one likes fireproofers.” It’s catchy. It’s true. And it speaks volumes about how we think about crisis, prevention, and the people who serve in both roles.

Before going on, some definitions are in order. For purposes of this article, a firefighter is someone who puts out fires when they occur. A fireproofer is someone who prevents fires from happening in the first place. The “fires” can be literal or figurative. We all talk about “putting out fires” at work, when there is no literal flame or smoke involved. We love firefighters. We love to be firefighters. But no one seems to like fireproofers.

It’s only natural that we prefer the one over the other. We are mentally hard-wired to value bravery and as a species we also tend to be lazy and resentful at being corrected, or at being compelled to do things that inconvenience us. That’s why firefighters get their own sexy calendars and their own television shows, but the woman who politely suggests that you shouldn’t flick your lit cigarette into the dry grass while you wait at the bus stop is a “Karen.” Firefighters get Backdraft, while all fireproofers get is back talk.

But any good organization, inside or outside of the military, needs both. We need leaders and workers who will step in to fight those figurative–and literal–fires that inevitably crop up. Here’s why:

The Hero Effect

Firefighters—literal or metaphorical—are celebrated. They run toward danger, charge into burning buildings, and save lives in the heat of chaos. In the military, they’re the special operators dropped behind enemy lines. In politics, they’re the quick-response teams who jump into a media crisis. In business, they’re the turnaround executives who fix what’s broken and put out the metaphorical fires before they burn down the whole company. These people are hailed as heroes.

And rightly so—firefighters do heroic work. But the spotlight they stand in often casts a long shadow over a quieter group of people: the fireproofers. These are the planners, the thinkers, the quiet professionals who make sure the fire never starts in the first place. You don’t see them on the news, and you don’t write movies about them—but without them, the whole system collapses.

Fireproofing Is Boring… Until It Isn’t

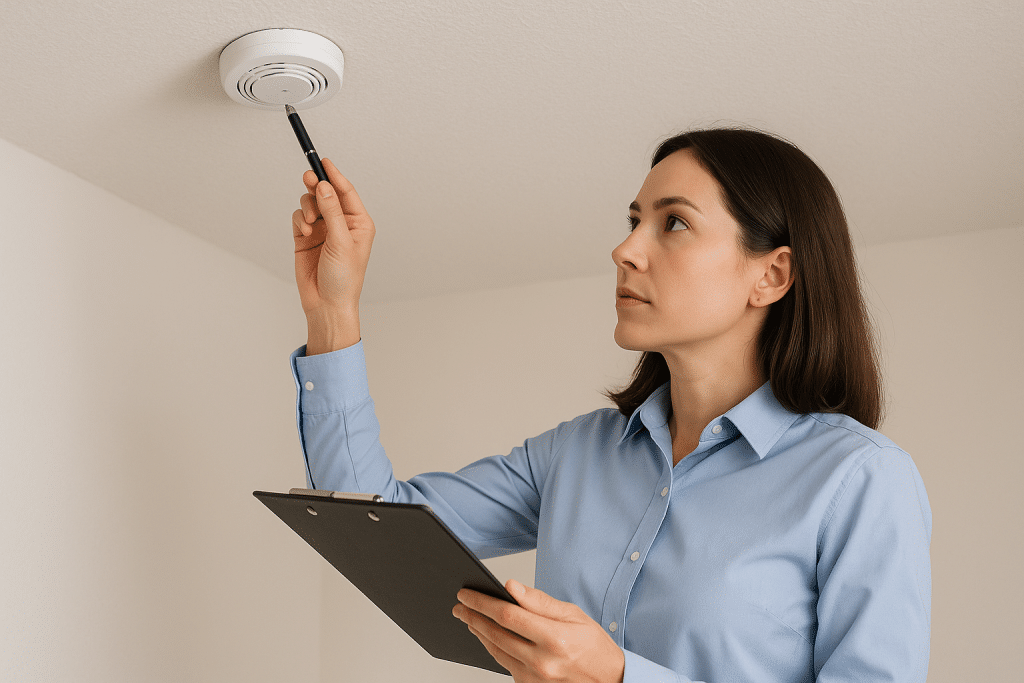

Fireproofing is the stuff of inspections, audits, redundancies, risk assessments, cultural change, and training. It’s the unglamorous side of heroism. Nobody cheers for the officer who rewrote the safety SOP or the staff sergeant who red-flagged a maintenance procedure before a bird went down. They’re not flashy, and they don’t come with cool action shots.

But here’s the truth: fireproofers save more lives than firefighters ever will. They just don’t get credit for it, because you can’t measure a tragedy that never happened.

Why We Hate Fireproofers

We hate fireproofers because they’re inconvenient. They slow things down. They ask uncomfortable questions. They challenge assumptions, push back against haste, and say things like, “We’re not ready yet.” Fireproofers get labeled as pessimists, obstacles, or—God forbid—bureaucrats.

In the military, that might be the JAG who kills your mission plan for violating ROE. In government, it’s the policy analyst who says your popular legislation has downstream constitutional problems. In tech, it’s the cybersecurity guy who locks down a product and delays launch.

Nobody applauds these people in the moment. They only seem valuable in hindsight—usually after the fire.

Crisis Junkies and the Addiction to Drama

We’re culturally addicted to crisis. We lionize the fast-twitch response and underfund the slow-drip preparation. The problem with this mindset is that it creates systems built to react, not to endure.

There’s also ego involved. Firefighting gives you adrenaline and medals. Fireproofing gives you spreadsheets and suspicion. In an environment where promotions and recognition hinge on visibility, the fireproofers often disappear from the chain of praise.

That’s not just unfair—it’s dangerous.

Warfighters and Warpreventers

What’s true at a micro level can be applied strategically as well. In the national security space, the stakes couldn’t be higher. We idolize the kinetic warrior—and we should—but we rarely lionize the strategist who found the diplomatic off-ramp or the intel officer who spotted the fuse before it was lit. These people are war preventers, not warfighters.

Our strategic culture must evolve to value both. Because while firepower ends wars, fireproofing keeps us from entering them in the first place.

It’s the same in the business world as well. We lionize the people who snatch salvation from the jaws of catastrophic failure. And we should. But what do we do with, and for, the people who keep it from getting to that point in the first place?

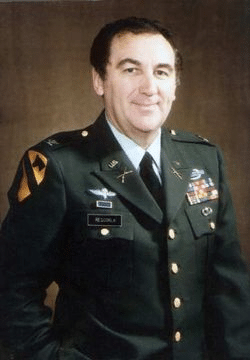

As a military professional with more than 27 years of service, the defining strategic event of my professional lifetime was 9/11. There were no shortage of hero stories in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. But the one that was the most memorable to me, and the one I think is the most relevant both to this article and the platform on which it appears, is that of Rick Rescorla.

Rick’s story is a long and interesting one. An immigrant to America, he served his adopted country in the Vietnam War and participated in the Battle of Ia Drang in 1965, which is the same battle that was highlighted in the movie We Were Soldiers starring Mel Gibson. Rick was also featured on the cover of the book We Were Soldiers Once… And Young, which inspired the movie.

After he left the Army, Rick started a job with the finance company Morgan Stanley, working in downtown New York City. Recognizing the potential terrorist threat to the building and Morgan Stanley’s employees and unable to convince his bosses to relocate to New Jersey, Rick got busy fireproofing. One of the things he did in his security role at Morgan Stanley was to institute fire and evacuation drills. As you might expect in a large for-profit company operating in a time-sensitive environment, these actions were not particularly well-received. This is especially true when considering that their offices were dozens of floors above the Manhattan street. Nonetheless, Rick persisted. He oversaw evacuation drills that occurred every three months, so that if the worst happened, his people would be ready. No one made him do this. He saw a potential issue and he stepped in to fix it before it became a problem. That’s what good fireproofers do.

Rick prepared for the worst, and the worst happened on September 11th, 2001. The building where Rick worked, on the 44th floor, was the North Tower, also known as World Trade Center 1. No one expected terrorists to attack the Twin Towers with passenger planes, but they did. And when the worst happened, Rick was ready.

This was the second time that Rick Rescorla was in the World Trade Center when it was attacked by terrorists. Despite being told by the Port Authority to “shelter in place” after the first plane hit on 9/11, Rick immediately began evacuating his coworkers. And they knew what to do… because of Rick’s fireproofing. Anyone who groused about having to push away from the desk to participate in Rick’s earlier evacuation drills was probably glad for the practice, especially when the lights went out and the smoke started coming in.

Rick had a bullhorn–because of course he did–and directed the evacuation of Morgan Stanley’s employees and numerous others who streamed down the steps and towards salvation. Quickly leaving his office on the 44th floor, Rick calmly directed the escapees to freedom, reminding them to “be good Americans, walk down slowly.” By some accounts, he sang while he did so. He helped evacuees to stay focused, telling them to stop crying and keeping them focused on what they needed to do to survive.

After getting as many of his coworkers out of the building, he went back in again and again to help evacuate more people, promising that he would leave as soon as he knew everyone else was out. He was in the North Tower when it collapsed. His remains were never recovered.

Rick was a firefighter on 9/11. He wasn’t the type of firefighter like many of the ones who died on 9/11, the ones with the hoses and the trucks and the sirens. But he fought the fires of chaos that day in his own way. While he is remembered and celebrated for his heroics on 9/11, he should also be remembered for his fireproofing. That preparation, in the face of resentment and ridicule, undoubtedly saved lives. That kind of foresight, and the strength of will to implement it, is something we need to recognize, cultivate, and encourage in our organizations. Because when the fires start, you’ll be glad that things around you aren’t going up in flames.

Conclusion: Shift the Culture

If we want a smarter, more resilient society, we need to reframe how we think about prevention. We need to elevate the fireproofers and build systems that reward foresight instead of merely reacting to the fires of failure.

The next time someone tells you, “We dodged a bullet,” find out who moved the target. They may not wear a cape or carry a hose—but they might just be the reason you’re still standing.

Charles Faint served over 27 years in the US Army, which included seven combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan with various Special Operations Forces units and two stints as an instructor at the United States Military Academy at West Point. He also completed operational tours in Egypt, the Philippines, and the Republic of Korea and earned a Doctor of Business Administration from Temple University as well as a Master of Arts in International Relations from Yale University. He is the owner of The Havok Journal, and the views expressed herein are his own and do not reflect those of the US Government or any other person or entity.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2026 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.