For the past several years, I have dived into the world of Neuroscience, Exercise Science, Psychology, Neurophysiology, Stress Response, and many other disciplines. I became even more curious as to why humans react a certain way during high stress situations. Whether it is combat, police action, working in an emergency room, EMS, Fire Department, or executive protection. I am not a trained doctor or anything like that. I’ve read books, tested theories, lived through some horrifying things and have managed to keep myself moving. Now comes the question: what in the world have I been doing?

Over the past several decades, law enforcement selection has become a joke from within the ranks. Especially those who have a passion for training. This check-the-box method of training is not working nor has it ever worked. “Death by PowerPoint” is another method police officers are subjected to when it comes to training. If we were to really look into how adult humans learn, we would realize that sitting down for hours and looking at PowerPoint is not the way to do it.

The training of Law Enforcement officers must be something of a challenge and showing the practical application of criminal law and criminal procedure. Sure, police officers get in-service training at least once a year. What is in-service training? It’s usually a weeklong “seminar” in which officers go over legal updates, implicit bias training, CPR and first aid training, as well as various other topics. Most of the time, the officers are sitting down for eight hours a day and just reading PowerPoint slides. Most of the time, officers could barely stay awake. They are very dry, although important, subjects. The delivery though needs to change.

Several years ago, I started looking into biofeedback type devices. At the time, I had an Apple Watch. I’ll never forget, after nearly shooting and killing a really bad guy, my watch went nuts. My heart rate reached 209 bpm. Here is a quick story about the situation. During COVID, District Attorneys across certain states decided to release suspects from jails to ease the strain of COVID regulations. Now, this particular suspect we were going after was a really bad gang enforcer for a local street gang in a large city. The team commander and I did our work ups and our research into this suspect. He was in fact very bad and our probability of a shootout with him were very high.

It was early morning in the big city, the team went to the briefing room and then we got ready. During the briefing, one of the lead detectives said that we need to be careful because the local District Attorney is looking to “fuck a cop.” Now, I’m #1 through the door with a 50-pound rifle shield. So my thoughts were, oh great just what I needed to hear. Long story short, we made the entry, I saw the bad guy run into a room. I entered that room and saw him reaching for a Glock with an extended magazine. He stopped short of actually grabbing it because I was already on him. I let go of the trigger after I saw his hands go up and the arrest team went in and placed him in handcuffs.

As I said before, my heart rate reached 209 bpm at that time. Several days later, I had to think about it. I’ve been an athlete for my entire life. From elementary school all the way through college. I consider myself, even now, in somewhat decent shape. I started reading a lot. Now I can go into the The Dunning-Kruger effect, which is a cognitive bias that occurs when someone with limited knowledge or skills in a certain area overestimates their abilities. But I will simplify it. The effect is named after psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, who first described it in 1999. It’s based on the idea that people who lack expertise in a certain area don’t have the skills to recognize their own limitations. This leads them to overestimate their knowledge and performance.

Now, let’s apply this to my situation, I am on a team that trains heavily. We are constantly refining and advancing our skillset. This is a luxury of being on a SWAT team. Let’s think of the average patrol officer who work the streets. They do not have the luxury of training like SWAT operators. They go to a six week to six-month academy, get bombarded with information, given a gun to qualify with and head to their respective agencies when they graduate the academy. These recruits enter a 12-week Field Training Officer (FTO) program, which is like jumping into the deep end of a pool and learning how to swim. The FTO is usually a senior officer with a wealth of institutional knowledge and experience. After the 12 weeks are done, the recruit is now an officer and gets assigned a shift.

You might be thinking: “ok, so what’s the problem?” Once training is done, it is done. The only other training the officer would get would be if the department or state hosted additional training. Once again, the training is more “check the box.” Can you imagine if our pilots just had to accompllish check the box training? Or if surgeon just do check the box training. No real test of proficiency? No real test under duress or an elevated heart rate?

The profession of law enforcement is 90% boredom and 10% high intense action. Complacency gets to the officers quickly if they are not careful. The question is: how does an officer train for that 10%? This is where technology and understanding Neuroscience comes in.

Biofeedback Devices

I have studied and used a variety of biofeedback devices. They all have their niches in the athletic world but what I was looking for was something more detailed. As I tried different devices, I honed in on Whoop ® and the Oura Ring ®. Now of course I have to give a quick disclaimer, I am not being paid by anyone, this is my honest feelings about the devices. Both of them are excellent and detailed. The only negative I would say with Oura Ring is that I have to wear it on my fingers. In a job where I have to use my hands, I don’t like wearing any ring on my finger. Especially my trigger finger, I even cut the index fingers off my gloves. It’s more of a personal preference.

I’ve had Whoop device for over four years now. The amount of data at the tips of my fingers is truly incredible. I not only use it to workout, but also to measure my recovery rate and even how I’m doing at work. If I deal with an intense situation, I like seeing where I was both mentally and physically before, during, and after the call for service. Here is an example of that.

It was in the morning, I was just driving in my cruiser after I ate some breakfast. I am a patrol Sergeant at my job. All of a sudden, dispatch reports of a male party walking in the middle of a street with a handgun. Now look at my graph. You can see how my heart rate shot right up around 145 bpm. Then you see a quick dip down then back up and then a gradual drop. What does this tell me? Well I have gotten to the point where I do combat breathing as I am approaching the location. That’s where the initial drop was from. Then as I’m working out the problem in front of me, as in coordinating with my officers on where they need to be, positions, shields, less than lethal options etc. You can see how all those factors are playing into an elevated heart rate. Now the reason our bodies respond this way, I will explain in simple terms, we are being “primed” and ready to act based on the information we already know. There are usually a lot more unknowns than knowns with these types of calls. So my mind and body are “primed” and ready to perform. Now for someone who does not train then they are not prepared. That’s where The Dunning-Kruger effect comes into action.

This is another call for service, something more recent. I was inside dispatch, it was a mild weekend on a Sunday. Not really crazy busy but steady. A 911 call comes in and the person on the other line is screaming about his roommate coming after him and his girlfriend with a machete. Now look at my heart rate. Can you guess when I got there and when we encountered the subject? So how does all this tie into training police officers.

Why are these devices so important, as an individual who consults and trains people, whether law enforcement, military or civilians these devices assists the user with critical information about their own reactions under stress. Unless officer train under stress, officers can never achieve the peak performance that is needed for when that 10% hits.

There is another part to these devices that will help an individual and leader assess their officers, soldiers, and workers.

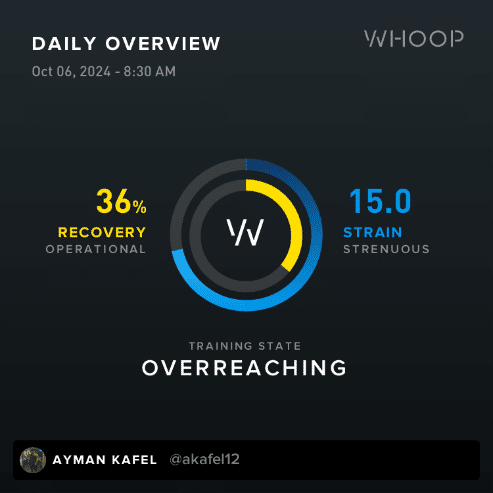

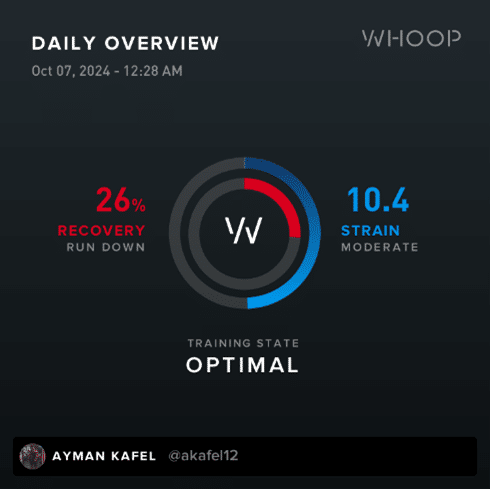

This is the main page of the Whoop App. Let’s see what’s going on here. The data on the left side shows that I worked and did not get enough rest from the prior day and shift. What I can tell you is I got ordered into work for the midnight shift. So, I worked my regular shift, got ordered in for the midnight shift. This means I went home to try to get a couple of hours of sleep for the midnight shift. That’s all I managed to get. I woke up at around 2200 hrs and made my way to work. I worked the midnight shift, then was ordered to work the evening shift on that same day. I had to go home once again at the end of shift and get some sleep. In total, between the two days, I got a total of 3.5 hours of sleep. Studies have shown that if a person doesn’t get the necessary amount of sleep, when they are driving, they are cognitively affected as if they drank a lot of alcohol.

There was a study that I read titled, “Effects of fatigue on driver performance.” The study revealed several significant findings regarding the effects of fatigue on driver performance. It demonstrated a notable increase in average response time for fatigued driving tasks compared to non-fatigue tasks, with the highest recorded response time reaching 1.23 seconds in the last quarter of an hour (Muneer et al., 2021). Additionally, participants exhibited a marked decrease in alertness during fatigued driving, as measured by the Stanford Sleepiness Scale (SSS), indicating a higher degree of drowsiness among fatigued drivers (Muneer et al., 2021). The research highlighted that sleep deprivation, defined as not obtaining at least 7 hours of sleep, significantly impairs both physical and mental performance while driving, posing a considerable safety risk. Let’s look at my numbers again, with getting only 3.5 hours of sleep and doing the job, am I really prepared to perform? The short answer is of course not. These types of things is what leaders need to look at when it comes to training, scheduling and recruiting more personnel.

Leveraging technology and neuroscience presents an opportunity for enhancing training in law enforcement and other high-stress professions. The exploration of biofeedback devices, such as Whoop and Oura, offers valuable insights into physiological responses during critical incidents, equipping officers with the ability to monitor their mental and physical states in real-time. By understanding how stress affects their performance, officers can engage in more effective and tailored training methods that go beyond traditional “check the box” approaches.

The current methods of training often fail to account for the unique demands of the profession, which can lead to complacency and reduced readiness. Integrating technology with a solid grounding in neuroscience can help bridge this gap, allowing for more immersive and realistic training experiences that prepare officers for the unpredictable nature of their work. Acknowledging the role of factors such as fatigue, emotional regulation, and cognitive performance is essential for developing a training framework that truly prepares law enforcement personnel to excel during the critical moments of their careers. Ultimately, by adopting a more evidence-based approach to training, we can enhance not only individual officer performance but also the overall safety and effectiveness of law enforcement agencies.

Reference:

Muneer, A., et al. (2021). Effects of fatigue on driver performance. *Engineering and Technology Journal, 39*(12), 1919-1926.

____________________________________

This first appeared in The Havok Journal on October 11, 2024.

Ayman Kafel and his family survived civil wars in Africa and Lebanon before immigrating to the United States in 1988. Following the tragic events of September 11, 2001, Ayman enlisted in the Army and deployed to Iraq in 2005, where he conducted over 20,000 miles of combat patrols and military missions. His proficiency in Arabic allowed him to effectively coordinate and collaborate with various Army units.

In October 2007, Ayman began his law enforcement career as a police officer in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, initially serving with the MBTA Transit Police Department. In 2011, he transferred to the Attleboro Police Department, where he has held multiple roles, including uniform patrol officer, detective, and DEA task force officer. He has also served as a DEA SRT Operator and assistant team leader, as well as a Metro-SWAT Operator, and he remains an active member of the SWAT team.

Throughout his career, Ayman has led and participated in numerous complex investigations, successfully capturing and prosecuting high-level criminals. In November 2022, he was promoted to the rank of Sergeant and currently serves as a Patrol Division Sergeant on the day shift.

Ayman is a writer for The Havok Journal, where he has published over 100 articles covering topics such as law enforcement issues, his military experiences in Iraq, and the challenges of PTSD within the law enforcement community. His work has also appeared in The Epoch Times. Recently, he was featured on BBC Arabic to share his insights and experiences in Iraq.

Additionally, Ayman has published a book titled *The Resolute Path* and founded Project Sapient, a podcast, training, and consulting company.

Follow Project Sapient on Instagram, YouTube, and all podcast platforms for engaging content. Feel free to email Ayman at ayman@projectsapient.com.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2026 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.