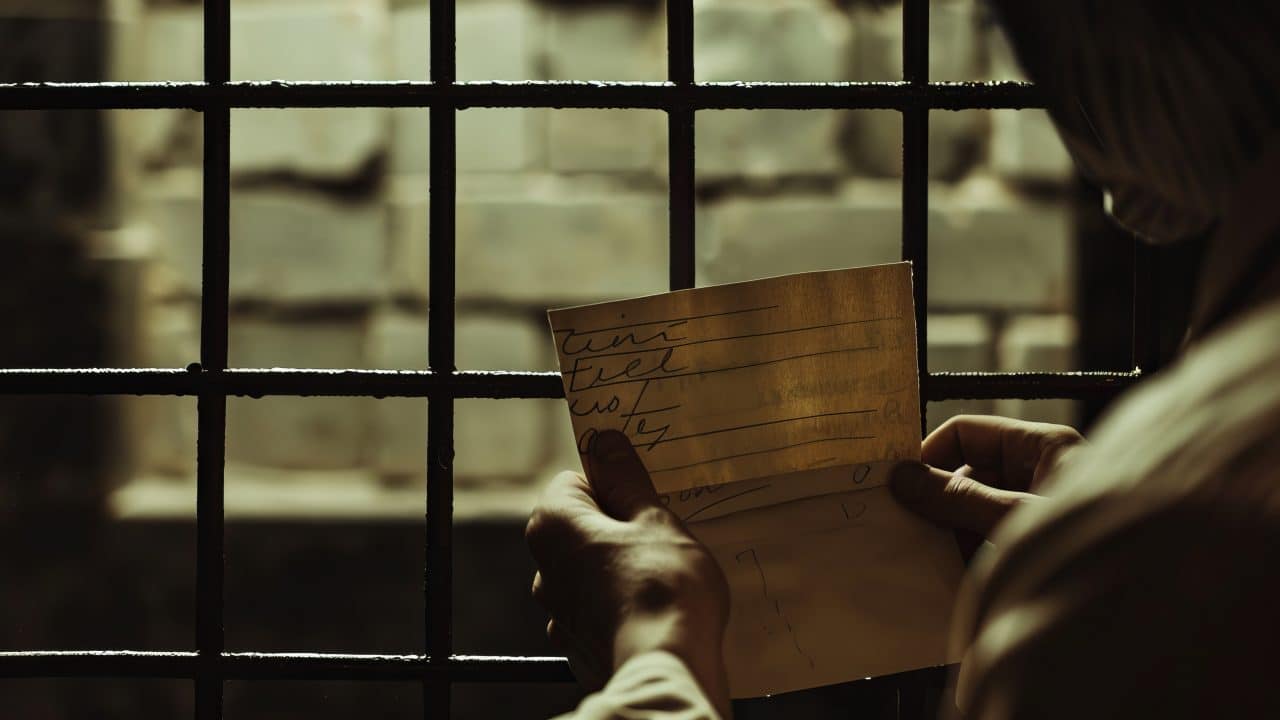

A friend of mine is in jail. The odds are good that he will go to prison. Keeping in contact with him is difficult. There are certain times when he can call me, but I can’t call him. He probably has no access to the internet, so emails, texts, and social media are out of the question. That only leaves the slow and archaic practice of writing snail mail letters to each other. That’s what we do, and that’s probably what we’ll have to do for the foreseeable future.

I like to write letters. I’m aware that many people do not. I have children who aren’t even sure how to use a postage stamp. However, the ability to communicate with pen and paper still comes in handy at times. Over the years, I’ve written letters to numerous people who weren’t able to interact with others except through the postal service. Some of these individuals were in nursing homes, some were deployed overseas with the military, and some were incarcerated. In a world where many—if not most—people can reach out to someone anywhere at any time, there is a population that, for a variety of reasons, is isolated from the rest of humanity. They depend on actual, physical letters.

My father spent his last years in a nursing home. He lived about three hours away from me, so my visits were infrequent. He wasn’t much interested in talking on the phone, and honestly neither was I. I don’t think he ever learned how to use a computer. So, I wrote letters to him, every week. I just told him about how things were in our family. Writing helped me to organize my thoughts and express them clearly. He never wrote back. Not once.

One time, during a visit with him, my dad made a point of telling me how much he appreciated those letters. Even though he didn’t write back (he hated to write), he was always pleased to receive mail from me. Those letters were our connection, albeit tenuous and one-sided. It was all we had.

Several years ago, I wrote letters to a young man from our neighborhood who had joined the Marines. I wrote to him while he was in basic training at the base in San Diego. He wrote back. We corresponded until he was out of boot camp. Then he lost interest in my letters. I understand that. He was busy having adventures. However, my letters might have helped him get through basic training. They let him know that somebody on the outside cared about him. I know that during my first year at West Point, letters from friends and family kept me going. Those letters were like gold.

I have often written to people in jail or prison. I guess I hang out with a bad crowd. Anyway, I’ve written to people who were incarcerated for serious crimes, and I’ve written to people who did time for civil disobedience. The folks who were in jail or prison for CD broke the law as a matter of conscience. They committed a crime because of their religious and/or political beliefs. They were usually antiwar activists. Hell, I went to jail for civil disobedience. I was in for only a day, but I got some small understanding of how it feels to be on the inside. It’s a lonely place.

One incarcerated person told me that other inmates were envious of her because she received a lot of mail, while other prisoners did not. I can see that. When a person is isolated from society, they can easily feel forgotten—and sometimes, they’re right about that. Some people in prison or nursing homes never get letters. It’s like they no longer exist. If a person feels that alone, it can destroy them. Humans need companionship. They need to be needed.

So, I write letters.

___________________________________________

Frank (Francis) Pauc is a graduate of West Point, Class of 1980. He completed the Military Intelligence Basic Course at Fort Huachuca and then went to Flight School at Fort Rucker. Frank was stationed with the 3rd Armor Division in West Germany at Fliegerhorst Airfield from December 1981 to January 1985. He flew Hueys and Black Hawks and was next assigned to the 7th Infantry Division at Fort Ord, CA. He got the hell out of the Army in August 1986.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2026 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.