During my 27 years as an officer in the US Army, I had the opportunity to do some really interesting things and to work with some really great people. This was especially true during my assignments in the Special Operations Forces (SOF) community. My time in SOF included seven combat tours to Iraq and Afghanistan with the 5th Special Forces Group, the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, and the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC).

While I was in JSOC our unit was commanded by two extremely capable individuals, first General Stanley McChrystal and then Admiral William McRaven. Professional intellectual broadening of the force was important to both of them. When he commanded JSOC, then-Lieutenant General McChrystal would occasionally send out various publications that he wanted all of us to read. These were often academic articles used in business school programs, designed to expand our mental boundaries and to help us develop creative ways to solve the very complex, high risk, and extreme-consequence problems we regularly encountered.

At first, I didn’t really understand why the commander of JSOC was giving us homework. After all I wasn’t in business school, I was in the business of wrecking al-Qaeda. I thought my time might be better spent reading Inspire or The Looming Tower rather than the Harvard Business Review. But, in the time-honored game of “rock-paper-rank,” O9 beats O4 every time. So because it was important to him, it became important to me.

One article in particular that I remember to this day was a summary of the book “The Starfish and the Spider,” which used a metaphor of the aforementioned animals to describe two primary organizational types. To summarize, a spider organization’s nerve center is centralized; so if you cut off its head, it dies. In contrast, starfish don’t even have heads, and if you slice one up and throw it back into the ocean, you have an even bigger problem because some of those parts can become separate animals.

For a long time, we had visualized Al Qaeda as a spider organization–cut off its head (bin Laden and his immediate lieutenants) and the body would wither. But we needed to see AQ more as a starfish. And to destroy a starfish, we need to get into it at the center and rip it apart in all directions so that it can’t just reform and spread its tentacles elsewhere. That shift in thinking–“spider” to “starfish”–was, of course, why GEN McCrystal had us read that piece in the first place. It was academia providing insights to the top manhunting SOF unit in the world. It was wisdom from an unexpected source.

I later crossed paths with GEN McChrystal when I was in grad school at Yale, where in retirement he taught an extremely popular (yet for some reason also highly controversial–read the rebuttal here) course on leadership. In the interests of full disclosure, the only reason I even applied to Yale was because GEN McChrystal taught there. I never saw myself going to Yale. I didn’t want to go to Yale. Yale wasn’t “my people.” My people were University of Alabama or Texas A&M or maybe even Duke. I wasn’t Yale material; I went to high school in Fayetteville, NC, and I only went to college because my dad told me that was the only way I could be an Army officer like him. Besides, people like me didn’t go to schools like Yale. But, as I mentioned in an earlier article right here on The Havok Journal, if Yale was good enough for “Stan” (as he insisted we call him in the class), it was good enough for me.

General McChrystal’s course on leadership was everything I expected, and more. Some of the most interesting, highest-achieving, and most intellectually curious graduate and undergraduate students I ever worked with were in that Leadership course, as well as in the Grand Strategy seminar headed up by historian John Gaddis. Those two courses were the academic highlights of my time in graduate school.

I recently re-connected with a fellow veteran and Yalie who also took McChyrstal’s Leadership course while in grad school. We had a long history together. We both joined the Army, we both went to grad school at Yale, we both taught in the same department at West Point, we both once served in the same overseas location at the same time, and we later both worked at the same SOF-focused think tank. I hadn’t talked to him in a while, so as is my tradition on Veterans Day, I called him.

As we were wrapping up the conversation, my friend casually mentioned that he planned to retire from the Army after he completed his current command assignment. This surprised me, since I strongly believed that he had general-officer potential. He is extremely intelligent, exceptionally competent, was loved by everyone, and had completed all of the requisites necessary to reach the Army’s highest levels, including being a multi-tour combat veteran. But he was tapping out.

I’m sorry. What?

My friend was, as the saying goes, the best of us. And he was leaving the Army when, in my opinion, he was knocking on the door to a general’s stars. When I asked him why he was hanging it up when it was pretty clear that he still had a bright future in uniform, he responded with a question of his own.

“Do you remember The Inner Ring by C. S. Lewis? We read it for McChrystal’s class.”

Yes. Yes I do. But before I talk a little more about that, I think I need to provide some backstory.

Part of the reason I went into the SOF community and deployed as many times as I did was out of a sense of what we might now call FOMO, or “fear of missing out.” My father is an Army veteran who served in a lot of units we would call “high speed:” 82nd Airborne Division, 5th Special Forces Group, JSOC, SOCOM, and towards the end of his career he commanded a unit that many people still call Task Force Orange. He was a veteran of Panama and Desert Storm. So I was around all of that–and those kinds of people–while I was growing up. I aspired to be one of them. I aspired to be in that inner ring.

I think that most soldiers will tell you that serving in combat is kind of the ultimate military credential. You can have all the badges and tabs, go to all the schools, be in the highest of high-speed units, but if you never went “down range,” there was something… missing. You’re not quite in the ring. I was a little over halfway through my tour in Korea when 9/11 happened, and was in training at Fort Leavenworth when we started “Bombs over Baghdad” in 2003. Based on America’s most recent conflicts, such as Grenada, Panama, and the first Gulf War, I was sure I’d be the only kid on my block without a combat patch. FOMO was real. So I went to where the action was, which for me was the 5th Special Forces Group. After some time there, I made the jump across the airfield to the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, and when I got promoted out of that job, I landed at JSOC. My total of seven (very safe, very short) combat tours was a lot, yes, but in JSOC at that time, that number of deployments was on the low end of average. There were people with three, four, five more tours than I had, and several of them stayed in SOF and kept deploying after I left. And while I was in SOF I definitely wasn’t “missing out” on an exciting mission set.

But while I was doing all those “inner ring” things, I realized that at the same time I was missing out on something else. Even though I was a very small cog in a very large machine, I was a fly on the wall in a lot of significant meetings and had access to an incredible amount of public and classified information. It was apparent even to me that we were never going to do the kinds of things it would take to win in either Afghanistan or Iraq. So why was I putting my physical and mental health at risk, having comrades die, and putting my family through all of that separation? It was time to go do something else.

So, I decided to roll the dice and submit an application to teach at West Point.

…and that roll of the dice turned up snake eyes. Rejected. Busted. Crapped out. Whatever gambling metaphor you want to use, that was what happened that year. And two or three more times after that. The details aren’t important for this story, but eventually I got picked up to teach at the Department of Social Sciences, which I argue is the most influential department at West Point. So yeah, I guess it all worked out. They sent me to school and helped me (because, God knows, I needed the help) get into Yale.

Yale University? Me? The guy who didn’t want to go to college in the first place–and had the grades to show for it–was on his way to one of the best universities in the entire world? The guy who was never the “cool kid” in anything, ever? The guy was always outside the inner ring? Wow, I guess I finally made it. Seven deployments and three SOF assignments, and now the Ivy League. Plus a great wife and two healthy and happy kids? Wow. FOMO? Never heard of her. As far as I could tell, I wasn’t missing out on anything.

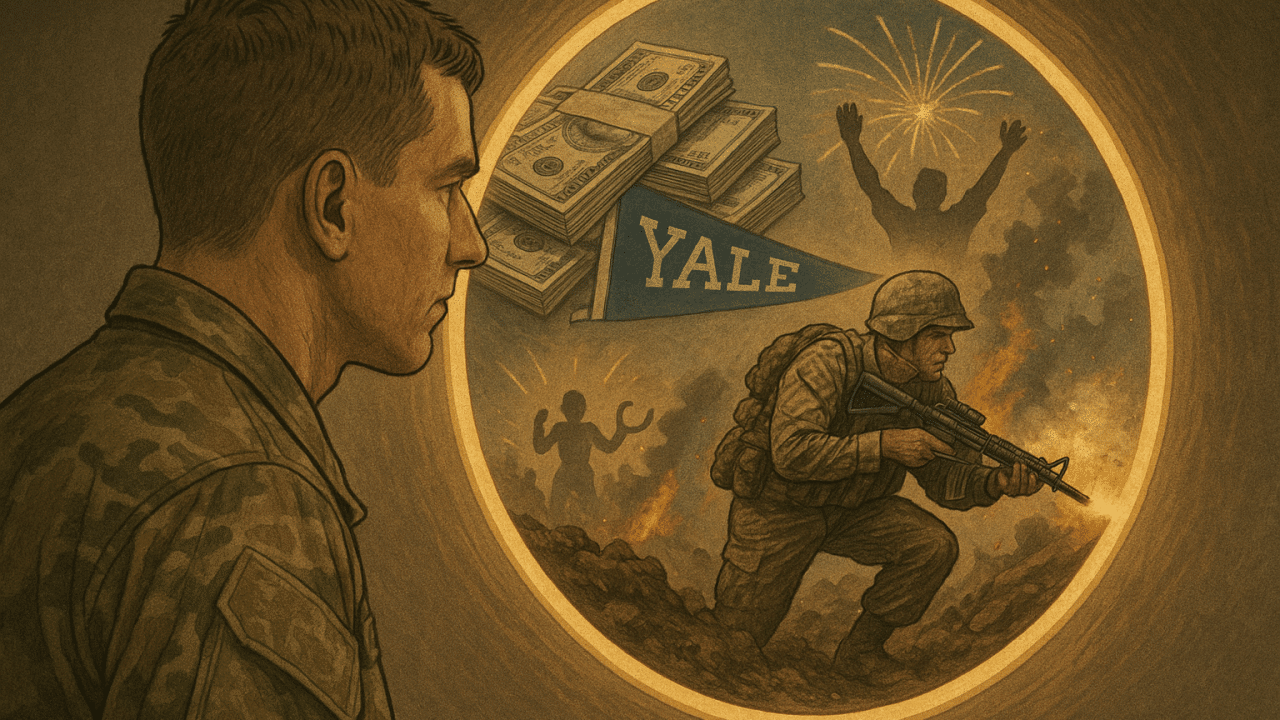

So, eventually, there I was, at Yale, in Stan McChrystal’s class on Leadership, on the road to teaching in the best-known department on West Point, literally living the dream. And that brings us back to The Inner Ring. For those who didn’t take Stan McChyrstal’s class on leadership or otherwise haven’t come across it in their reading, C.S. Lewis (yes, the same guy who wrote The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe and countless other tracts and tomes) wrote The Inner Ring as a warning about the basic human desire to for inclusiveness, achievement, and elite status–and its dangers. It is not a particularly easy read, as it is written in the style of the times and makes a few references that may be unfamiliar to some modern readers. So here’s a contemporaneous explanation of the work.

As I mentioned earlier, in modern terms, we might describe the phenomenon of chasing that inner ring as FOMO–fear of missing out. The problem is, taken to its extreme, FOMO means you will never be “in” enough. There is always one more ring, literal or metaphorical. You will keep chasing that next group, that next acolade, that next thing. You will keep chasing that next ring. In high school, it was the cool kids’ circle. In college, it was getting branched Infantry. Once in the infantry, it was getting into intel. Then, into the SOF community. And then getting deployed a bunch. And then into the Ivy League school. And then… and then… and then…

…because there is ALWAYS going to be something you’re missing out on. But when you get to the end, when you get to as far as you can go, there will always be something left undone. And you may find that what you missed out on along the way, were the things that really mattered all along. That’s what C.S. Lewis, a foreigner author known for Christian-inspired fantasy novels writing long before I was even born, warns us about. The Chronicles of Narnia guy was helping be become a better military leader. Once again, it was wisdom from an unexpected source.

We read The Inner Ring early on in GEN McCrystal’s leadership course. In fact, it may literally have been Lesson One. I don’t recall, it has been 12 years. But I remember the main points, just like I did from that earlier assigned reading, The Starfish and the Spider. My friend clearly remembered the key takeaway from The Inner Ring as well. When he reminded me of us reading it, no further explanation was necessary. He was giving up on the inner ring of the military–perhaps even the Pentagon’s famous E-Ring itself–to do the things that really matter.

Something else that is important to remember about the inner ring is that it doesn’t care about you. Like, at all. This was a point that another friend of mine brought up after I initially published this article, and I thought it was important enough to add in. The inner ring is an unfeeling machine. Even if you’re part of it–even if you’re the head of it–one day you won’t be. And the machine won’t care. It was there before you, and it will be there after you. The ring endures. We do not.

Although I didn’t go to school at West Point, I taught there longer than most graduates spent there, and I work there now in retirement. Something I tell all of the cadets is, “get in the best unit you can, as soon as you can, and stay there as long as you can.” That has a very “inner ring” tone to it. But I also tell them, “no matter how long you stay in the Army, you’ll eventually leave the Army or the Army will eventually leave you. But if you do it right, your family will always be there.” Basically, I warn them not to FOMO their way out of the thing that will sustain them later in life and the reason I believe we’re all here: our families. You can have ambition. You can have drive. You can want to go to war or go to Yale or go to JSOC or any number of other goals that are out there. Just don’t fall into the trap of inner ring while you do it.

My time in the Army is over. There are no more deployments. No more degrees, no more diplomas. Yale is a pennant I have on my office wall. JSOC is a distant dream. But my family and my friends, my health and my sanity, my integrity and my legacy, I have all of those. That is the inner ring that matters. And I think that is what C.S. Lewis was talking about. I’m grateful that General McChrystal had the foresight to help his students, young and old, understand what’s really important in life. And that it’s not the inner ring.

My Army buddy and Yale friend is, as of this month, now retired. So while I’m sad that my Army colleague and fellow Yalie will no longer serve the nation in uniform, I get it. More than that, I support it. FOMO is useful, but we have to fear missing out on the right things.

…and I’m glad my friend found his own “inner ring.” the REAL inner ring. the one that matters. But, as the best of us, I think he knew where it was all along.

Good luck in retirement, brother. You’ve earned it.

Lieutenant Colonel (Retired) Charles Faint currently works at the United States Military Academy at West Point. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect an official position of any component of the US Government.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2026 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.