Author’s Note:

My name is Charlie Faint. I’m a 27-year veteran of the US Army, and I served in Iraq and Afghanistan seven times, all with Special Operations Forces (SOF) units. I am also the owner of The Havok Journal. Over the years, we’ve published a lot of original content that I’m very proud of. But one of the most powerful pieces we’ve ever run was something we reposted.

In January 2019, I read a poem called “The Morning After I Killed Myself” by Meggie Royer on social media. I was deeply moved by its power and asked her if we could re-post it on The Havok Journal. She graciously allowed us to do so, and every year we re-publish it.

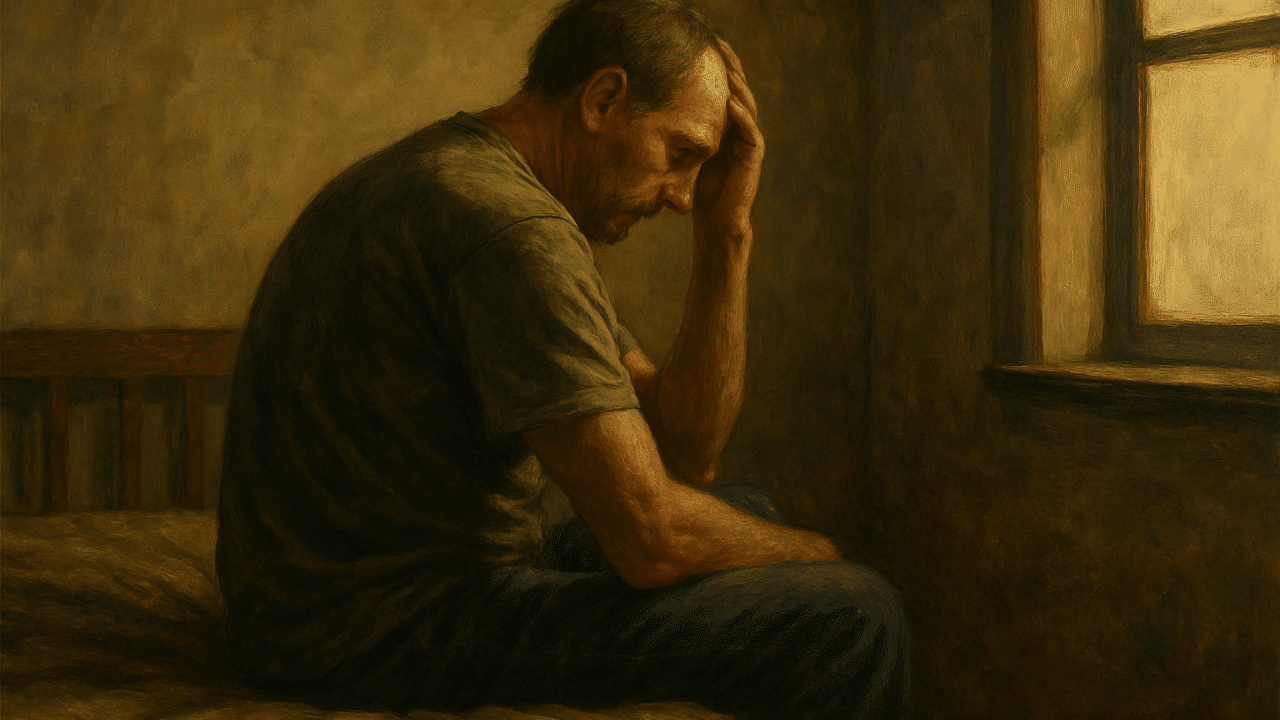

In September 2025, the veteran community was rocked by another spate of veteran suicides—something that happens far too often. The common statistic is that military veterans kill themselves at an average rate of 22 per day. In our community, it’s common to hear someone refer to becoming “one of the 22” as a euphemism for suicide. While the exact number is debated, it’s absolutely true that veterans take their own lives at a higher rate than the civilian population.

The point I want to make—and that I want every veteran to hear and believe—is that it doesn’t have to be that way. The veteran community needs you. Don’t quit on yourself. Don’t quit on us. Your mission isn’t over yet.

Veteran Suicide Hotline: Dial 988 then press 1, chat online, or text 838255

The day after I made myself one of the 22, I woke up to Reveille.

I grabbed an MRE—chili mac, my favorite—and rinsed it down with a Rip-It.

I went for a run, hit the bench press, and recorded a new personal record.

The day after I made myself one of the 22, I called for my dog, Sally—the one who was always there for me. She needed me, and I needed her. When I called, her tail twitched at a noise no one else could hear, and she looked at someone no one else could see: me.

She ran through the house looking for me, but I wasn’t there. She listened for a command that never came; when she found me, I was gone.

She sat with her face to the door, waiting for me like she always did. Except this time, she waits for orders that will never come.

She fades away.

The day after I made myself one of the 22, I laughed with my brothers and sisters-in-arms at their stories about us—about me. About my goof-ups and the things I did well. They raised their glasses and shouted my name. But they looked sad. And when I called for a toast—“To us, and those like us, damn few left!”—they didn’t hear me. Because I wasn’t there.

The day after I made myself one of the 22, I locked eyes with the spectral version of my mother, kneeling over maps of my childhood, tracing paths she thought I’d take—not the paths that led me here.

I watched my father on the riverbank of regret, rolling a message inside a tube and sending it downstream, hoping someone would intercept.

I saw my brothers and sisters—by birth and by blood—and the hole that I left in them. A hole that all the 550 cord and 100-mile-per-hour tape couldn’t fix. I saw all the people who cared about me, the ones I knew and the ones I didn’t, but they couldn’t see me.

Not anymore.

The day after I made myself one of the 22, dawn cracked the sky. Orange flares stretched across the horizon like open fingers—like orange chemlights. No, more like star clusters. Like the ones I should have blown when I realized I was going down this road.

The day after I made myself one of the 22, I sat down with my corpse—the shell of what I once had been, the dust of what I could have become. Who would take care of Sally now that you’re gone?

The morning after I became one of the 22, I tried to undo it all. But there was no unbecoming.

…it didn’t have to be this way.

— Adapted with gratitude from the original by Meggie Royer.

_________________________________

Lieutenant Colonel (Retired) Charles Faint served 27 years in the US Army, including seven combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan with various Special Operations Forces units. He also completed operational assignments in Egypt, the Philippines, and the Republic of Korea. He is the owner of The Havok Journal and the executive director of the Second Mission Foundation. The views expressed in this article are his own and do not reflect those of the US Government or any other person or entity.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2026 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.