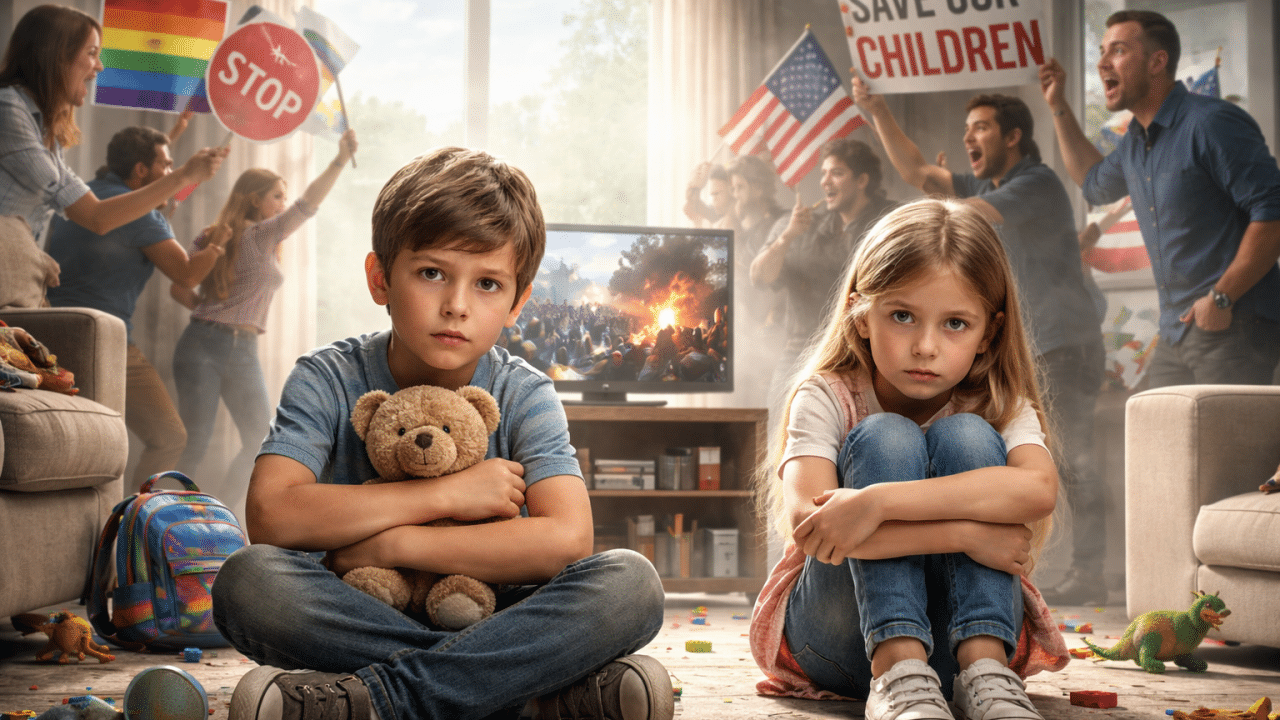

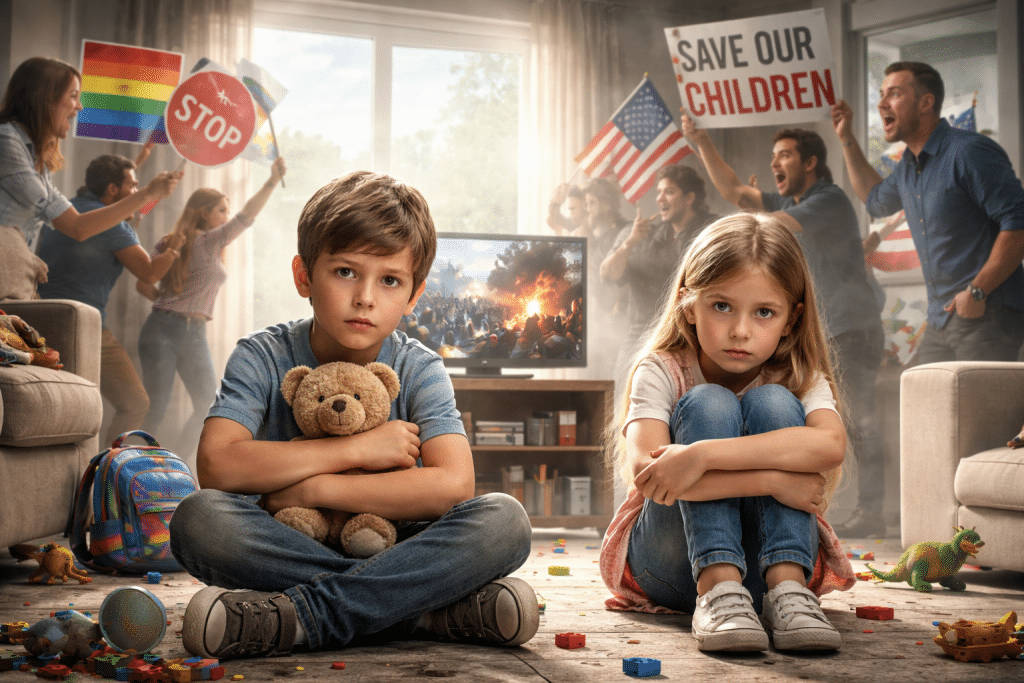

Children are not miniature adults. Their brains are unfinished systems still wiring emotional regulation, threat assessment, and identity formation. They are biologically dependent on adults not just for food and shelter, but for psychological safety. Yet modern culture increasingly treats children as ideological participants in adult conflicts they cannot meaningfully understand.

Politics, gender ideology, immigration enforcement, social justice movements, and cultural grievance narratives are no longer confined to adult spaces. They are injected into classrooms, family conversations, social media feeds, and even playtime. Children are not merely informed of these conflicts; they are asked to feel them, react to them, and, in many cases, choose sides.

This is not education. It is psychological exposure to adult-level conflict without adult-level capacity.

The New Normal: Children as Participants, Not Observers

A generation ago, children were largely shielded from adult disputes. Disagreements existed, but they were background noise, not the emotional climate of childhood. Today, many parents and educators no longer believe shielding is necessary, or even desirable.

Children are now routinely exposed to:

• Moralized political narratives presented as settled truth

• Adult fear and outrage framed as urgent crisis

• Pressure to adopt public stances on complex issues

• Social cues that silence or punish dissent

What is often justified as “awareness” or “raising compassionate kids” frequently crosses into emotional enlistment. Children are not learning how to think. They are learning what to fear, who to distrust, and how to signal ideological loyalty.

Developmental Reality: Children Cannot Process Abstraction Like Adults

One of the most ignored realities in this debate is developmental psychology. Children, particularly before adolescence, do not think abstractly in the way adults do. They process information concretely and emotionally. When adults speak in metaphor, urgency, or moral absolutism, children interpret those messages literally.

When a child hears that democracy is collapsing, that people like them are under threat, or that silence equals harm, they do not hear rhetoric. They hear danger. They internalize the idea that the world is unstable and that safety is conditional on correct belief.

Adults often mistake children’s ability to repeat slogans for understanding. What children are actually doing is absorbing emotional tone, not nuance. The cost of this misunderstanding is chronic anxiety disguised as moral engagement.

Fear Conditioning and the Shaping of Worldview

Children exposed to repeated adult alarmism undergo fear conditioning. This is not hypothetical. The brain adapts to perceived threat by prioritizing vigilance over exploration.

Over time, these children learn that:

• Conflict is omnipresent

• Authority figures are emotionally volatile

• Stability is fragile

• Moral mistakes carry social punishment

This produces a baseline worldview of threat rather than curiosity. The child does not simply worry about specific issues; they grow into a person who expects danger and moral failure everywhere.

Once this worldview is established, it does not fade easily. It becomes the lens through which adulthood is experienced.

Moral Injury Without Agency

Moral injury is typically associated with soldiers or first responders who are forced into ethical contradictions beyond their control. Children increasingly experience a similar phenomenon, without the maturity or autonomy to resolve it.

Children are told they are complicit in injustice simply by existing within certain systems. They are warned that neutrality is immoral. They are taught that disagreement equals harm. Yet they possess no real power to change the conditions they are blamed for.

This creates guilt without agency, one of the most corrosive psychological states a developing mind can experience. The child is burdened with responsibility but denied control. That imbalance produces shame, anxiety, and identity confusion.

Parentification: When Children Become Emotional Caretakers

One of the most damaging consequences of adult ideological conflict is parentification. Children are increasingly expected to manage adult emotions.

They are asked to reassure distressed parents, validate adult anger, or act as emotional allies against perceived enemies. This role reversal places children in a position of emotional labor they are not equipped to handle.

Parentified children often grow into adults who:

• Struggle with boundaries

• Feel responsible for others’ emotions

• Avoid conflict at all costs

• Tie self-worth to approval

What begins as political passion ends as emotional exploitation, even when unintentional.

Schools as Authority Amplifiers

When ideological messaging comes from parents, children at least retain some ability to contextualize it as opinion. When it comes from schools, it carries institutional authority.

Teachers are not just adults. They represent systems of evaluation, approval, and discipline. When schools present contested social issues as moral certainties, children receive a clear message: correct beliefs are required for acceptance.

Disagreement becomes risky. Curiosity becomes dangerous. Independent thought becomes a liability.

Education shifts from developing reasoning skills to enforcing conformity, not through overt punishment, but through social pressure and authority-backed signaling.

Peer Enforcement and Social Punishment

Once children internalize ideological frameworks, enforcement rarely stops with adults. Peer groups quickly take over.

Children learn which opinions are safe and which invite exclusion. They self-censor to avoid social punishment. Classrooms become environments where silence feels safer than honesty.

This is not civic engagement. It is social conditioning.

Children raised this way often struggle later with open dialogue, disagreement, and compromise, not because they are malicious, but because they were trained to associate dissent with danger.

The Loss of Play and Psychological Recovery

Play is not optional. It is how children process stress, regulate emotion, and integrate experience. When adult conflict saturates their environment, play loses its restorative function.

There is no mental refuge. No downtime. No space free from moral urgency.

Overstimulated children do not become more aware. They become dysregulated. The result is rising anxiety, behavioral issues, and emotional exhaustion mislabeled as maturity.

The Myth of “Building Resilience”

Some adults argue that exposure to conflict builds resilience. Psychology says otherwise.

Resilience is built through secure attachment, manageable challenges, and recovery after stress. Constant exposure to adult-level conflict without recovery time does not build strength. It builds fragility masked as toughness.

Children need stability before they can face complexity. Without it, they fracture under pressure they were never meant to carry.

Long-Term Consequences

Children raised in ideological battlegrounds often become adults who:

• Interpret disagreement as threat

• Substitute emotion for reasoning

• Seek authority to enforce moral order

• Struggle with ambiguity and uncertainty

This is not merely a parenting failure. It is a societal one.

Conclusion: Responsibility Without Ideology

This is not about which political position is correct. It is about who bears the psychological cost of adult certainty.

Children should not be the collateral damage of ideological warfare. They should not be drafted into conflicts they cannot comprehend, manage, or escape.

Adults have every right to argue fiercely among themselves. They do not have the right to make children pay the emotional price for those arguments.

Context is education. Command is indoctrination. And childhood should never be the battlefield where adults fight their wars.

References

Child Cognitive and Emotional Development

(Psychological limits on abstraction, emotional processing, and moral reasoning)

• Piaget, J. (1952). The Origins of Intelligence in Children. International Universities Press.

Foundational work on stages of cognitive development, including limits of abstract reasoning in children.

• Steinberg, L. (2014). Age of Opportunity: Lessons From the New Science of Adolescence. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Explains neurological immaturity in emotional regulation and decision-making.

• Giedd, J. N. (2015). “The Amazing Teen Brain.” Scientific American.

Details brain development timelines relevant to stress and emotional processing.

Chronic Stress, Anxiety, and Fear Conditioning in Children

(How repeated exposure to threat reshapes worldview)

• McEwen, B. S. (2007). “Physiology and Neurobiology of Stress and Adaptation.” Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873–904.

Landmark paper on cortisol, chronic stress, and long-term brain effects.

• Shonkoff, J. P., et al. (2012). “The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress.” Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246.

Defines toxic stress and its neurological and psychological impacts.

• Perry, B. D., & Szalavitz, M. (2017). The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog. Basic Books.

Case-based exploration of how children internalize adult stress and threat.

Moral Injury, Guilt, and Psychological Burden

(Guilt without agency and identity confusion)

• Litz, B. T., et al. (2009). “Moral Injury and Moral Repair in War Veterans.” Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 695–706.

While focused on adults, establishes the framework of moral injury applicable to non-combat contexts.

• Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). “Moral Emotions and Moral Behavior.” Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345–372.

Explores shame, guilt, and moral development in children and adolescents.

Parentification and Emotional Role Reversal

(Children absorbing adult emotional labor)

• Boszormenyi-Nagy, I., & Spark, G. M. (1973). Invisible Loyalties. Harper & Row.

Foundational text defining parentification.

• Hooper, L. M. (2007). “The Application of Attachment Theory and Family Systems Theory to the Phenomena of Parentification.” The Family Journal, 15(3), 217–223.

Empirical analysis of long-term psychological outcomes.

• Chase, N. D. (Ed.). (1999). Burdened Children: Theory, Research, and Treatment of Parentification. Sage Publications.

Comprehensive academic treatment of emotional role reversal.

Authority Influence, Conformity, and Social Pressure

(Schools, teachers, and peer enforcement)

• Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to Authority. Harper & Row.

Classic research on authority influence and compliance.

• Asch, S. E. (1955). “Opinions and Social Pressure.” Scientific American, 193(5), 31–35.

Foundational study on conformity under social pressure.

• Wentzel, K. R. (2017). “Peer Relationships, Motivation, and Academic Performance.” Educational Psychology Review, 29, 205–225.

Shows how peer dynamics influence behavior and self-censorship.

Play, Recovery, and Emotional Regulation

(The necessity of psychological downtime)

• Gray, P. (2013). Free to Learn. Basic Books.

Explains play as a mechanism for emotional regulation and resilience.

• Pellegrini, A. D. (2009). The Role of Play in Human Development. Oxford University Press.

Neurological and developmental importance of play.

Resilience: What Actually Builds It

(Debunking exposure-based resilience claims)

• Masten, A. S. (2014). Ordinary Magic: Resilience in Development. Guilford Press.

Defines resilience as secure attachment plus manageable challenge.

• Rutter, M. (2012). “Resilience as a Dynamic Concept.” Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 335–344.

Emphasizes recovery and stability, not chronic exposure.

Long-Term Societal and Psychological Outcomes

• Twenge, J. M. (2017). iGen. Atria Books.

Documents rising anxiety, emotional fragility, and social stress in younger generations.

• Haidt, J., & Lukianoff, G. (2018). The Coddling of the American Mind. Penguin Press.

Examines moral absolutism, fragility, and threat-based thinking in youth culture.

_____________________________

Dave Chamberlin served 38 years in the USAF and Air National Guard as an aircraft crew chief, where he retired as a CMSgt. He has held a wide variety of technical, instructor, consultant, and leadership positions in his more than 40 years of civilian and military aviation experience. Dave holds an FAA Airframe and Powerplant license from the FAA, as well as a Master’s degree in Aeronautical Science. He currently runs his own consulting and training company and has written for numerous trade publications.

His true passion is exploring and writing about issues facing the military, and in particular, aircraft maintenance personnel.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2026 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.