Karin and I went to Pulaski Park at 9:00 a.m. The sun was shining, and the weather was already warm. We strolled to the tiny greenspace from Brady Street to help set up for the festival. Most of the prep work had already been completed: banners hung, tables laden with snacks. The kindergarteners, including our grandson Asher, were scheduled to arrive at 9:30. They would walk the two blocks from the Waldorf school to the park with their teachers.

In the meantime, Karin and I, along with some other caregivers, used our artistic skills to make chalk drawings on the ground near the children’s obstacle course that had been set up in the tennis court. We drew multicolored trees, flowers, stars, suns, whales, and spirals. The little kids would have a chance to view the drawings later in the morning when they navigated the obstacle course.

In addition to the obstacle course, there was face painting, a sack race, and other activities. The park playground was expected to draw plenty of attention, too. The kids could munch popcorn, chew on apple slices, and eat dragon bread smothered with butter (vegan or dairy) and blackberry jam.

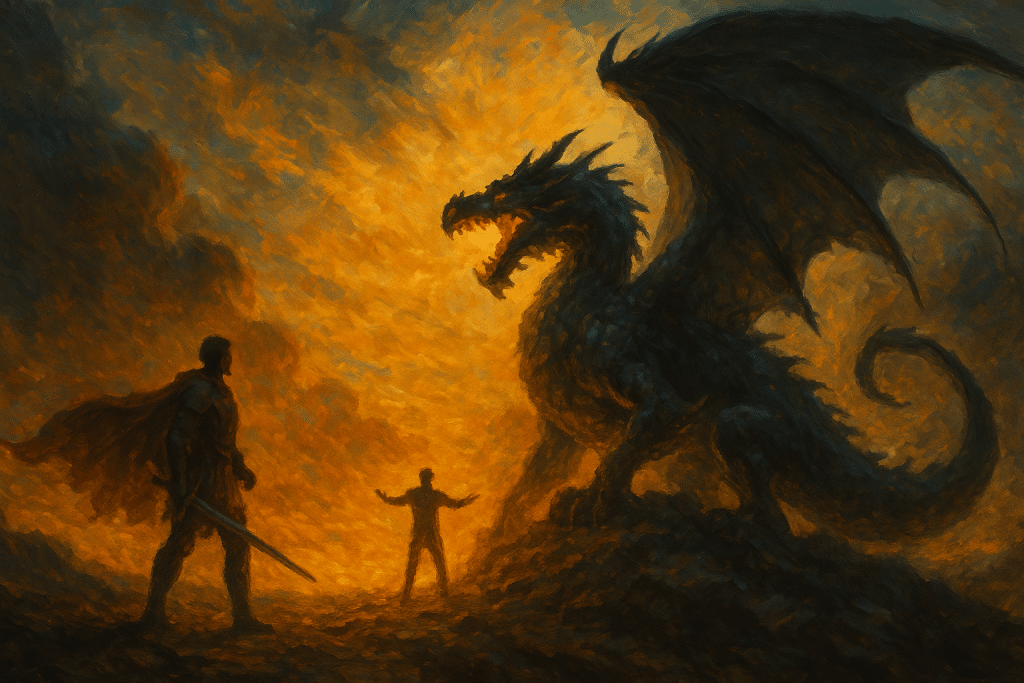

Dragon bread probably needs an explanation. It reminds me a lot of challah bread, except instead of being braided, it’s molded into the shape of a dragon. See below:

That isn’t the best possible image, but you get the idea. Why does the festival feature dragon bread? That requires a bit of background on the whole event.

Waldorf education is a little over a century old. Rudolf Steiner, the founder of Waldorf schools, drew inspiration from medieval religious holidays to help children stay in tune with the seasons of the year. Years ago, when our own children attended the school, the festival was called Michaelmas, a day still marked on the Catholic Church’s calendar. Michaelmas is the feast of Michael, Raphael, and Gabriel—the archangels. They are seen as examples of courage, combating the forces of evil in the world. There used to be a mural in the school showing St. Michael slaying a dragon—the dragon symbolizing chaos and darkness.

Are archangels real? Even if they aren’t, they symbolize the courage to do what’s right. In today’s more secular and diverse times, the event is called the Festival of Courage—a fitting theme that has remained constant.

Asher and his classmates arrived dressed for the occasion. They all wore yellow capes and orange headbands that looked like crowns or halos. Once the three kindergarten classes and their caregivers were gathered, we formed a large circle around a low, grassy knoll in the park. Halle, one of the teachers, led everyone in a short song:

“Morning has come, night is away, we rise with the sun and welcome the day.”

Then she told a story-poem about picking apples, complete with hand and body movements. Everyone joined in as best they could. Asher stood next to Karin and me in the circle. Nearby was Maggie, a little girl in his class who is friendly toward him—and he toward her.

When the poem ended, the crowd dispersed, and the children went off to play. They threw their “shooting stars” into the air—dark blue cloths wrapped around a small object and tied with brightly colored ribbons that the kids had made in class. Then Asher lined up for the obstacle course.

He had to crawl through a tunnel made of small tents, throw a ball through a hoop (he made it on the third try), and walk a balance beam. He needed his grandma—Oma—to hold his hand for that one. Asher was nervous about walking the beam, but he did it anyway. Courage doesn’t mean not being scared; it means doing something even when you are. It also means being willing to accept help when you need it.

What do St. Michael and the dragon have to do with courage? How does this festival teach children that virtue? Through stories, games, and symbols—dragon bread, capes, and song. The story of St. Michael gives a child a way to understand bravery through a simple, concrete image: a fight against something outside themselves.

Adults learn, too. I don’t believe courage is innate. It’s a virtue that must be taught and practiced throughout a lifetime. Courage takes many forms. St. Michael was a warrior—we assume warriors are brave. Yet the bravest person I’ve ever met was someone battling addiction. It’s easy to fight for our own rights, but how do we defend the rights of others? How do we wake each morning and slay the dragon within ourselves?

___________________________

Frank (Francis) Pauc is a graduate of West Point, Class of 1980. He completed the Military Intelligence Basic Course at Fort Huachuca and then went to Flight School at Fort Rucker. Frank was stationed with the 3rd Armor Division in West Germany at Fliegerhorst Airfield from December 1981 to January 1985. He flew Hueys and Black Hawks and was next assigned to the 7th Infantry Division at Fort Ord, CA. He got the hell out of the Army in August 1986.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2026 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.