We lean into our trekking poles with pounding hearts and labored breaths, slowly grinding our way up the 30-degree unimproved mountain trail that will take us to Gold Star Peak. Our legs are burning as we “hear” our late son, Quint’s repeated and slightly bemused mantra echoing in our consciousness–“What’re gonna do, not go?” We have read the trail logs and comments about this route and know this hike will be an immense challenge for us. The night before, we collectively laughed at the terse review: “If you don’t have trekking poles, you are dead.” Despite my general disdain for trekking poles- just something extra to carry that always seems to get in the way- our daughter, who we were visiting in Anchorage, Alaska- borrowed some for us Florida flatlanders. We are thankful for them as they help distribute weight and provide extra purchase on the steep incline among the loose, shifting shale slides that co-mingle our uphill path.

Gold Star Peak is a 4,148-foot mountain in the Chugach State Forest about 40 miles outside Anchorage, Alaska. On a map, it is only a 3.6-mile round trip, but as you look closer, those little squiggly lines (contour lines) denoting elevation gain (or loss) are densely packed, meaning it is STEEP- both ways. The trail guide says it is a “Black Diamond” hike with a 2800 ft elevation gain in that short (or long) 1.8 miles to the summit. Gold Star Peak was so named in 2018 to honor the families of military members who have died in service to our country. The Gold Star family is a tight-knit community that no one willingly wants to be a part of. It comes with an excruciatingly high entrance fee- the loss of a precious loved one while serving in uniform. We abruptly found ourselves in the Gold Star family when our son, SSG George L Taber V (Quint), a Green Beret Medical Sergeant, tragically died in a sudden storm while training at the Mountain phase of Army Ranger school on August 9th, 2022.

Our daughter lives in Anchorage, AK., so a trek up Gold Star Peak was a must-do when we visited her. She and her friend are skiers, climbers, and endurance athletes extraordinaire, so they patiently guide us and set a moderately comfortable pace for their just-shy-of-60-year-old parents to follow. This was a short and brisk training walk for them as they are training for a 50-mile endurance adventure race later this summer. But we were thankful for their company, and we soon realized that as hard as this climb was physically for us, the emotional toll would be even more significant. During these times, it was comforting to have a close-knit family with whom we could share our grief and understand the sudden springing flow of latent tears.

The climb has three distinct phases—four if you count the half-mile flat, paved Eklutna Lake Road that takes you from the roadside parking area up to the trailhead, which is just an unmarked path on the side of the road that would go unnoticed by the untrained eye. There is no marker, sign, or blaze, just a nameless trail headed straight uphill.

Phase 2 is a steep path with thick vegetation taller than our heads. It consists of towering Sitka spruce and Hemlock trees, Blueberry, Mountain cranberry, Devil’s Claw with its fierce thorny stalks, and beautiful blooming wildflowers. We shouted, “Hey, Boo Boo, there’s no picnic here for you, you!” and sang ditties and songs, hopefully giving Yogi the bear plenty of warning about our whereabouts. At one point, a thoughtful (or frustrated) hiker had anchored a section of rope to help scramble up a particularly steep and technical gully. Coming out of the heavy underbrush, we suddenly find ourselves on an open alpine saddle where you can see the ribbon of Eklutna road a thousand feet or so below. We also get our first glimpse of the steepness of the climb still ahead as we try to figure out which barren, rocky crag above is our final destination. We also get our first view of the sprawling Chugiak-Eagle River valley below. Visibility was nearly unlimited, and we were blessed to climb on a beautiful, clear day, which is apparently not the norm.

Phase 3 is an alpine slope devoid of all vegetation except grasses and scrub shrubs. It is a steep, rocky scramble. But now, there is enough room for freelancing, depending on your hiking style and the resiliency remaining in your knees and quads. We opted for mini switchbacks, zigzagging instead of bulldogging straight up the mountain face. We fell into the rhythm of:

Step, step, breathe, pause, step.

Step, step, breathe, pause, step.

Each step found us carefully determining the next foothold in the rocky scree. Often, even our intentional steps would dislodge loose rocks, and we would watch in wonder as they plummeted, crazily bouncing down the hill for hundreds of yards. We were thankful that no climbers were following us, and this spectacle made us even more careful, imagining the possibility of our unbalanced, somersaulting bodies replacing one of those careening rocks. Yet, we occasionally would look up and revel in the unmatched beauty of the climb, the mystery of seeing the path we had come but not knowing exactly where our path would end far above. Since we couldn’t sightsee and focus on our footing simultaneously, we would force ourselves to break out of our climbing rhythm, pause, look at the vast river valley below and the steep, craggy trail ahead, and take deep draughts of the beauty and crisp mountain air surrounding us.

Legs now screaming in revolt, Phase 4 brought us out of another saddle where we could see sparkling Eklutna Lake to our Southeast and the sprawling Knik River and Knik Arm watershed to our north and west, running back towards Anchorage. The trail ran along a sharp ridgeline toward the top. We attained a few false peaks along the way, only to find the trail still winding upwards. The exposed ridgeline we were climbing now unleashed its gusty winds, so the jackets we had shed earlier in the day were re-applied.

Then we see it, like a watchful sentinel standing guard at the top of a craggy hilltop. A simple 8-foot-tall obelisk with four sides facing North, South, West, and East. Affixed to its peak is a prominent Gold Star, like you would find atop a regal Christmas tree. The monument is rimmed with 21 circular wire levels representing the 21-gun salute, which honors the fallen at a military funeral.

Then we hear it.

How does a monument speak, you ask? This one speaks volumes. Affixed to the 21 wire circles are hundreds of dog tags and memorial bracelets, all chiming and clinking together in the breeze, making the sound of a dozen wind chimes tuned to the frequency of fresh ice stirred in a glass on a hot summer day. The hair on our heads stood up in rapt attention to this solemn, melodious tribute to the multitude of our finest men and women who died far too young protecting this great nation of ours. It is said that when climbing the mountain in clouds or fog, you often hear the memorial long before you see it, guiding the trekker onward by sound rather than sight. We are filled with a presence of reverent humility.

We are tired and glad to have finally reached the peak, but now the emotions overflow. We place Quint’s dog tag on an open space near the top on rung 19 or 20. We clasp the chain and ball socket into place. We attempt to utter a few words but then fall silent. Sometimes words can’t reveal what the heart feels, so we commune in the presence of wind-chimed whispers in another world, a parallel sphere of space and time, a place called heaven where only love, goodness, and laughter are present. We can hear them talking. They are all Okay on the other side, just waiting for us to join them. It won’t be long now. As if to punctuate the sanctity of the moment, we watch in wonder as three yellow butterflies wheel, dance around our heads, and skip off in playful unison down the mountain.

My walk, the grief journey that I have been on for nearly two years, has seemed like a heavy singular thing– like no one else in the world can feel the crushing weight, the relentless sorrow, the challenge to rise in the morning and face another day; to say his name and to recall memories that don’t answer back in the present tense. Being in the presence of these hundreds of heroes’ tags, glistening and clanking in the breeze on Gold Star Peak, reminds me that I am not alone, that hundreds of Mothers and Fathers, wives and children, brothers and sisters, loved ones, friends, and battle buddies also feel this singular and collective loss.

They know.

They see.

They understand.

I am not alone.

Not today.

Not on this mountain.

You are not alone.

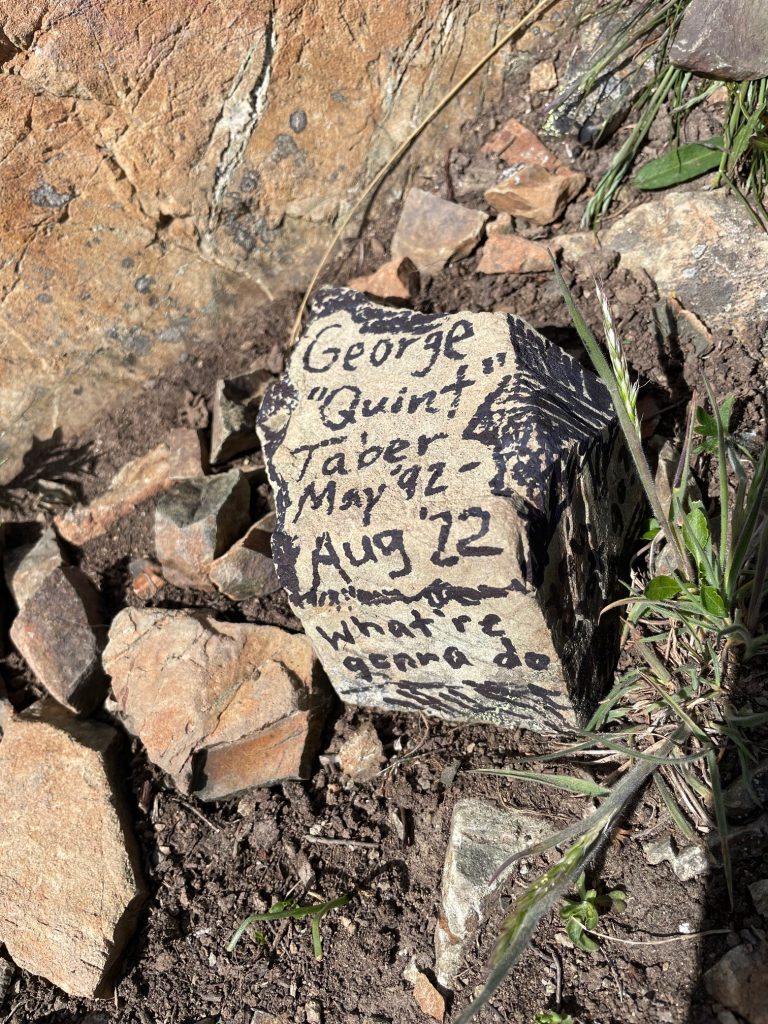

We sit on the simple stone benches beside the monument and have lunch. We begin exploring the tokens and remembrances that encircle the monument like a living, breathing memorial garden. A couple of Ammo cans are chained to a rock filled with notes, pictures, letters, mementos like plastic toy soldiers, ZYN dip cans, bottle tops from favorite beers, whiskey flasks, etc. Each item tells a private story we don’t understand, but we don’t have to because each little trinket symbolizes a personal love story that will live on for generations. A Cairn made up of painted rocks is mounded beside the memorial. Some are simple, some fancy, but all speak a special message to those who have been lost. Our daughter finds a suitable blank rock and inscribes a message to her brother with a black Sharpie. Unit challenge coins are sprinkled among the stones and coins of various denominations. We noticed coins left on our son’s gravestone at Jacksonville National Cemetery (FL) and looked up their meaning. The tradition dates to the Roman Empire and is a symbolic way to show respect to fallen service members and their families. A penny means a visitor paid their respects and visited the grave site. A nickel means the visitor went through training with the deceased. A dime means the visitor served in the same unit as the deceased. A quarter means the visitor was with the soldier when they died.

We lingered on Gold Star Peak for just over an hour, but in the back of our minds, we knew that our weary bodies would need to eventually make our way down the mountain, taxing new joints and muscle groups during the descent. We lengthen our trekking poles for the downhill run, occasionally slipping and sliding on the loose rock. Now, knees, ankles, and toes bore the brunt of our long descent back to our parked car. It had been about a 7-hour day. We were spent both physically and emotionally, but we were filled with the knowledge that we made a pilgrimage that we would remember for a lifetime. We came to honor our son, but we also honored the hundreds of other deceased service members and their families. It was also a hard thing, which Quint would approve of as he always sought “hard things” to do just because he could.

Rest in Peace, Heroes.

For more information about Gold Star Peak, go to goldstarpeak.org

“Bringing Veterans and Survivors together in nature to remember and honor the fallen and bring healing to all.”

____________________________________

This first appeared in The Havok Journal on July 31, 2024.

Tab Taber is a Gold-Star Dad–father of SSG George L. Taber V, a Green Beret Medical Sergeant from 7th SFG who died during a violent storm on Mt. Yonah while in the Mountain phase of Ranger School in August 2022. Tab journals to process his grief and to recollect memories of his son. Occasionally he shares his written thoughts with The Havok Journal and on Instagram @gltiv. He retired from the Military (8 years Marines;15 years Army) in 2014 and now resides in NE Florida where he runs a 4th generation wholesale plant nursery. He can be reached at tabtaber7@gmail.com.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2025 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.