In the suburban paradise where I reside, there is a tree in my front yard. I’m no arborist, but I think it’s an oak. It’s what we call a “City Tree.” City trees belong to the municipality and sit on city-owned property—in this case, on the strip of land between the sidewalk and the street in front of my house. Since that land belongs to the city, the tree does too.

I’ve lived here for over twenty years, and the tree has been here the entire time. It was already fully grown when I moved in. Throughout the city, thousands of trees just like it grow in that same narrow strip of land. They clearly didn’t sprout up naturally. Someone—probably the city—planted them as part of a beautification effort, attempting to “pretty up” the neighborhood. Back then, they were likely no taller than the average adult. Since then, they’ve done what trees do: they’ve grown.

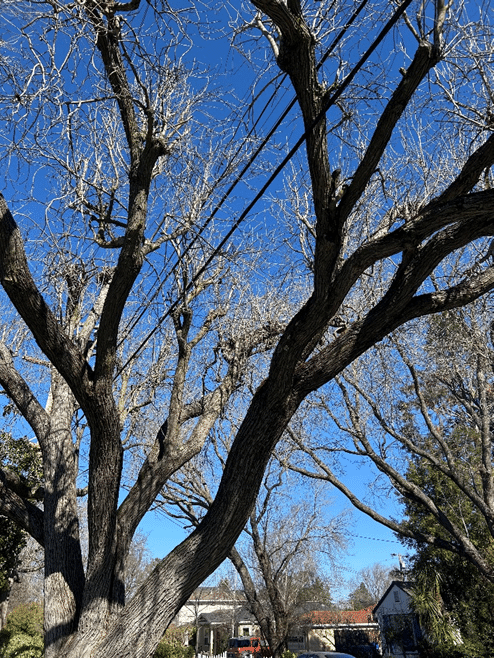

Now, my city tree’s branches are hopelessly entangled in the power, cable, and phone lines that once towered above it. Since the tree isn’t mine, I’m not allowed to trim it. Doing so would be considered vandalism—a violation of the law.

If you call the city, they’ll send a crew to trim it back a little, but the branches are so tangled with the wires that the workers can’t do much without risking electrocution or shutting off power to residents. The utility companies won’t do anything either, and realistically, it’s not their problem.

A few years back, the city tried to cut down a tree causing similar issues. This led to protests, lengthy diatribes in the media and at City Council meetings, and other forms of public outcry. Faced with the backlash, the city caved and vowed never to do it again.

Big trees don’t belong in urban sprawl. Their roots get strangled under asphalt and concrete. During what we call winter in California, we get heavy rain and strong winds, which cause large branches to snap off and, in some cases, entire trees to topple over. They tear through power lines, plunging neighborhoods into darkness. Last year, we lost power for two days; the year before, we were in the dark for three. Each time, a city tree was the culprit.

Falling branches, often weighing hundreds of pounds, land on cars parked in driveways and along the curb. Sometimes entire trees crash onto houses, destroying them. Even when the damage isn’t catastrophic, the trees create a cascade of smaller problems. They fall across roadways, blocking traffic. Their roots push up sidewalks, creating tripping hazards. People get injured stumbling over these uneven walkways, leading many to walk in the street instead—making them easy targets for passing cars. And that’s not even touching on what tree roots can do to septic lines.

If I wanted to voice my concerns to local officials in person, I couldn’t. Since COVID, most city employees have been working from home. City Hall is set up like a fortress. The outer doors are locked, so you have to be buzzed in. Once inside, you go to the front desk and state your business—only to be told that the person you need to speak with is “working remotely,” probably watching The View while collecting a paycheck. The whole experience is about as welcoming as a visit to the county jail.

City trees are a prime example of government ineffectiveness. Whoever planted them decades ago should have realized they’d become a problem once fully grown. Since they’re on city property, we can assume the city either approved their planting or directly funded the project. But politicians operate in the “here and now.” At the time, it seemed like a good idea. The consequences? Someone else’s problem.

As the trees and the problems they cause got bigger, no one did anything. Well, that’s not entirely true—they did try to cut down that one tree. But after public outrage, they never tried again. Realistically, most people probably wouldn’t have cared if the city had removed it. But a vocal few, with political clout and media connections, made enough noise to spook the politicians into submission. It’s yet another example of special interest groups—tree huggers, in this case—getting their way while everyone else is ignored.

At this point, the only real solution would be to cut most of the city trees down. But before that could happen, there would have to be an expensive, taxpayer-funded environmental impact study, likely conducted by a firm with close ties to government officials. If the study concluded that the trees should go, there’d be a drawn-out selection process to find a contractor. The winning company would, of course, need to check all the right boxes—eco-friendly, diverse, properly pronouned, and so on. In the end, it would probably be a firm that only pretends to meet these standards but happens to have the right political connections.

The city trees are just like the trees in wildfire-prone areas. Every fire season, they ignite, causing massive property damage and loss of life. These are trees that should have been cut down, but environmentalists and government agencies banned logging companies from removing them. Their lack of proper forest management has, in some cases, cost lives.

The city tree problem is part of a larger pattern. The same government mismanagement applies to homelessness, crime, and other urban decay issues. Politicians cause the problems—often through well-meaning but short-sighted policies—then cave to special interest groups when those problems spiral out of control. They only act when there’s money involved and when it benefits them or their political allies.

It’s also a classic case of liberal politicians micromanaging people’s lives. Another tree-related example? “Spare the Air” days. In California, the government tells people when they can and can’t burn wood in their stoves, based on predicted air quality. So if your home’s primary heat source is a woodstove and the state declares a “Spare the Air” day in January, you’re out of luck—either freeze or risk a fine.

Ironically, they declare these restrictions even when massive wildfires are burning thousands of acres—fires made worse by the same government policies that prevented responsible forest management. But sure, it’s your potbelly stove that’s the real air-quality issue.

So, the city trees stay. I’ve checked my small generator to make sure it’s ready for the inevitable power outage. I’ve stocked up on supplies and mentally prepared for yet another round of throwing out spoiled food when the fridge goes dark. I’ve done the “fridge purge” for the last two years, so I’m getting pretty good at it.

I wonder if they make silencers for chainsaws…

______________________________

Nick is a Police Officer with the Redwood City Police Department in Northern California. He has spent much of his career as a gang and narcotics investigator. He is a member of a Multi-Jurisdictional SWAT Team since 2001 and is currently a Team Leader. He previously served as a paratrooper in the U.S. Army and is a veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom. He has a master’s degree from the University Of San Francisco.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2026 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.