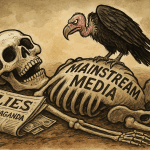

Somewhere along the way, news stopped telling us what happened and started telling us how we should feel about it. What was once the art of fact-based observation has morphed into a contest of outrage, sympathy, and partisan identity. Today’s headlines are often less about informing the reader and more about mobilizing emotion — fear, anger, pity, or moral superiority.

To understand how we got here, let’s examine two fictional but realistic examples: one written in the style of 1950s American journalism, and one written as a modern “emotionalized” article about the same event — a political demonstration in Washington, D.C.

1. The 1950s Report: “Capitol Demonstration Draws 3,000 Protesters”

WASHINGTON, D.C., April 14, 1955 — Approximately 3,000 demonstrators gathered near the Capitol building today to protest proposed legislation increasing federal fuel taxes. The event, organized by the Citizens for Economic Fairness Committee, began at 10:00 a.m. and concluded peacefully shortly after noon.

Police estimated attendance using aerial photographs and confirmed no arrests were made.

Speakers included Rep. Walter Briggs (R-OH) and economist Dr. Ellen Harper of Columbia University. Both criticized the tax proposal as “burdensome to working families.”

Capitol Police closed portions of Constitution Avenue during the march. Regular traffic resumed at 1:15 p.m. No injuries were reported.

White House officials declined comment on the demonstration.

This style is dry, objective, and — by modern standards — almost boring. Yet it accomplishes its purpose: to report verifiable facts.

Notable features:

- Measurable data (attendance, time, place)

- Direct quotes, attributed to named individuals

- Absence of adjectives implying moral judgment (“angry,” “patriotic,” “extremist,” etc.)

- Separation between event and interpretation

The reader is left to decide: Was the protest justified? Overblown? Heroic? That’s not the reporter’s job to say.

2. The Modern Version: “Fury Erupts at Capitol as Angry Crowds Denounce ‘Unfair’ Fuel Bill”

WASHINGTON, D.C., April 14 — Outraged citizens flooded the Capitol today in a fiery demonstration against what they called an “unjust assault” on working families. The diverse crowd, estimated at several thousand, chanted and waved handmade signs decrying lawmakers’ “greed” and “betrayal.”

The protest, described by organizers as a “grassroots uprising,” drew impassioned speeches from supporters who condemned Washington’s “war on the middle class.”

“We’re here because we’ve had enough,” said one mother of three, her voice trembling with emotion. “They keep taking from us while the rich keep getting richer.”

Opponents of the movement dismissed the demonstration as “politically motivated theater.”

The proposed fuel tax increase is part of the administration’s broader energy-transition plan, which experts say is necessary to combat climate change — a view the protesters vehemently reject.

Police presence was heavy, and some officers appeared hostile and aggressive as chants grew louder. No serious incidents were reported, but emotions ran high throughout the day.

For many, today’s protest symbolizes a major national divide between those demanding change and those defending the status quo.

3. Comparing the Two: How Emotion Replaced Observation

At first glance, both reports describe the same event. But look closer. The second article isn’t just reporting — it’s guiding how the reader should feel.

Tone and Adjectives

The 1950s piece is neutral: “Approximately 3,000 demonstrators gathered.”

The modern one begins with “Fury erupts” — instantly framing the event as chaotic and emotional.

Notice the adjectives and verbs: outraged, fiery, angry, betrayal, trembling with emotion, uprising. These aren’t facts; they’re emotional signals. They tell you how to react before you even reach the second paragraph.

Framing

The older version centers on what happened. The modern version centers on what it means.

In the 1950s, readers were expected to interpret events themselves. Modern media often assumes the audience needs help deciding who’s right or wrong. This leads to moral framing — positioning one side as the oppressed, the other as oppressors. It’s effective for engagement but corrosive for understanding.

Quotes vs. Commentary

The factual version quotes official sources and attributes opinions directly.

The emotionalized one uses selective quotes that amplify pathos (“her voice trembling with emotion”) while dismissing counterpoints as fringe (“opponents dismissed the demonstration as theater”).

Even when both include dissenting voices, the tone tells you which to sympathize with.

Omission and Emphasis

Modern articles often omit or bury neutral information.

The second version never specifies exact attendance numbers or duration — those data points aren’t felt; they’re known. Facts are less engaging than feelings, so they fade into the background.

In contrast, the 1950s article emphasized time, numbers, and outcomes. That’s because journalism once prized verifiability over virality.

Imagery and Emotional Cues

The modern report paints a vivid emotional scene: trembling voices, tense police, fiery passion. It appeals to empathy, fear, and belonging — the same instincts advertisers target.

This kind of narrative activates the limbic system, not the prefrontal cortex. Readers aren’t analyzing data; they’re feeling stories. Once emotion takes hold, confirmation bias fills in the rest.

4. Why Modern Journalism Changed

It’s tempting to blame politics alone, but emotionalized journalism is the product of multiple converging forces.

The Economics of Outrage

In the 1950s, newspapers sold by subscription and print advertising. There was limited competition. Today’s online news exists in an attention economy. Every click, share, or comment is currency. Outrage drives engagement far better than balance.

As algorithms reward emotional intensity, outlets amplify it. Calm, factual reporting doesn’t spread; anger does.

The Death of Shared Reality

Mid-century Americans read many of the same newspapers and watched the same three TV networks. That common informational baseline allowed disagreement within a shared factual frame.

Now, people live in media silos. Left, right, or alternative — each outlet curates emotional resonance with its own audience. The facts don’t have to change; the framing does.

Journalism’s Identity Crisis

Reporters once aimed to be invisible conduits of verified information. Today, many see themselves as narrative shapers or social advocates. This can produce noble journalism — uncovering injustice or amplifying silenced voices — but it also opens the door to advocacy disguised as reporting.

Power to Shape Policy and Perception

Walter Cronkite’s televised editorial on the Tet Offensive in February 1968 became a turning point in how Americans viewed both the Vietnam War and those fighting it. Although the offensive was a tactical failure for North Vietnam, Cronkite’s conclusion that the war was “mired in stalemate” contradicted years of official optimism and eroded public trust in the government.

As confidence in the war’s purpose declined, so too did public support for the troops themselves. Many service members returning home found themselves unfairly blamed for political decisions beyond their control. Cronkite’s shift in tone helped move the national conversation from patriotic unity to widespread disillusionment, fundamentally altering how Americans viewed their military and the meaning of service during wartime.

This singular event demonstrated to the media the power they held to mold the American psyche to whatever suited their needs. And it showed politicians that the press was a valuable tool that could be used for their own purposes — good or bad.

The 24-Hour News Cycle

The rise of the 24-hour news cycle fundamentally changed journalism by creating constant pressure to fill airtime and keep audiences engaged. As a result, networks increasingly shifted from straightforward reporting to opinion-based commentary and analysis.

Opinion segments are cheaper to produce than investigative journalism and generate stronger emotional responses, which help retain viewers in a competitive media environment. Over time, this emphasis on continuous commentary blurred the line between fact and opinion, turning many news programs into platforms for editorializing rather than objective reporting.

The result has been a media landscape where personality and perspective often overshadow accuracy and depth. There is more truth to the movie Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy than most people realize — it’s truly a documentary hiding in the guise of a comedy.

5. How to Spot Emotionalized News

Recognizing bias doesn’t require cynicism — only awareness. Here’s what to look for:

- Loaded Adjectives and Verbs

Words like furious, heartbreaking, stunning, or defiant are emotional amplifiers. A factual report doesn’t need them. Replace them with neutral terms in your mind — if the meaning changes, emotion is steering the narrative. - Anonymous or Vague Sources

“Experts say,” “critics argue,” or “many believe” often hide selective sourcing. Reliable journalism names sources or cites data. “Protected source” is a convenient way to mold a story into whatever you want it to say. - Moral Framing

When an article quickly divides participants into heroes and villains, you’re being fed a story, not a report. - Absence of Quantifiable Details

If you can’t find hard numbers (how many people, how long, where exactly), the writer might be avoiding verification. - Appeals to Shared Emotion

Phrases like “Americans are outraged” or “the nation mourns” assume collective feelings that can’t be proven. They’re rhetorical shortcuts for persuasion. - Opinion Creep

Watch for sentences that sound factual but express judgment:

“Police were slow to respond.” → Fact? Or opinion?

Compare: “Police arrived 15 minutes after the first report.” That’s verifiable. - Statistics and Numbers

Statistics and crowd numbers are powerful tools in shaping public perception, but they can be easily misused in the media to push a particular narrative. Who is reporting the crowd number — the event organizer or an impartial source? Are all those in the crowd actually supporting the event, or are some counter-protesters? Reporters or commentators may highlight selective data, use misleading comparisons, or cite unverified crowd estimates to exaggerate support or opposition for a cause. By emphasizing relative changes instead of absolute numbers, or by omitting key context — such as how figures were gathered or who provided them — media outlets can subtly manipulate interpretation while appearing factual. This misuse of statistics can create the illusion of consensus or crisis where none exists, influencing public opinion not through truth, but through presentation. Remember, there’s a huge difference between “those who died from COVID” and “those who died from something else while infected with COVID.”

6. The Psychological Cost of Emotionalized Media

When every issue is presented as a moral emergency, the public becomes emotionally exhausted and intellectually numb. People start reacting instead of reasoning.

This isn’t accidental. Emotional activation keeps audiences loyal — or addicted. Each headline becomes a small dose of adrenaline or indignation. The result: citizens who feel informed but are often misinformed, armed with passionate certainty but few confirmed facts.

It also breeds cynicism. When readers finally notice manipulation, they often swing to the opposite extreme — distrusting all media. That skepticism, though understandable, creates fertile ground for conspiracy and polarization.

7. Returning to Objectivity — or at Least Honesty

Pure objectivity may be impossible; humans interpret everything through context. But honest reporting is still possible — and necessary.

Here’s how readers and journalists can reclaim it:

- Demand Attribution. Ask “Who said this?” before believing it.

- Reward Precision. Support outlets that list data, sources, and direct quotes.

- Value Boring Truths. Facts aren’t always dramatic — but they are reliable.

- Separate Analysis from News. Opinion pages have their place, but labeling matters.

- Challenge Your Own Bias. If an article makes you feel vindicated before you finish it, stop and verify.

8. Why It Matters

The erosion of factual reporting isn’t just a journalistic problem; it’s a civic one. Democracies depend on a population capable of discerning reality from rhetoric.

In 1955, readers expected the who, what, when, where, and why. In 2025, they often settle for how it feels. That shift may be the single greatest vulnerability in our information ecosystem.

The next time you scroll through headlines, remember the two demonstrations — the one reported with facts and the one wrapped in emotion.

One tells you what happened.

The other tells you what to believe.

Only one of them leaves you free to decide. The other aims to manipulate you.

________________________________

Dave Chamberlin served 38 years in the USAF and Air National Guard as an aircraft crew chief, where he retired as a CMSgt. He has held a wide variety of technical, instructor, consultant, and leadership positions in his more than 40 years of civilian and military aviation experience. Dave holds an FAA Airframe and Powerplant license from the FAA, as well as a Master’s degree in Aeronautical Science. He currently runs his own consulting and training company and has written for numerous trade publications.

His true passion is exploring and writing about issues facing the military, and in particular, aircraft maintenance personnel.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2025 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.