by Charles Evered

[Editor’s Note: The following was written by Charles Evered as a remembrance of George Roy Hill, his former professor at Yale and the celebrated director of The Sting, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and other classics. In light of the recent passing of Robert Redford—and given that Hill himself was a veteran of both World War II and Korea—Charles felt this would be a fitting time and place to share this reflection. We at The Havok Journal couldn’t agree more.]

__________________________

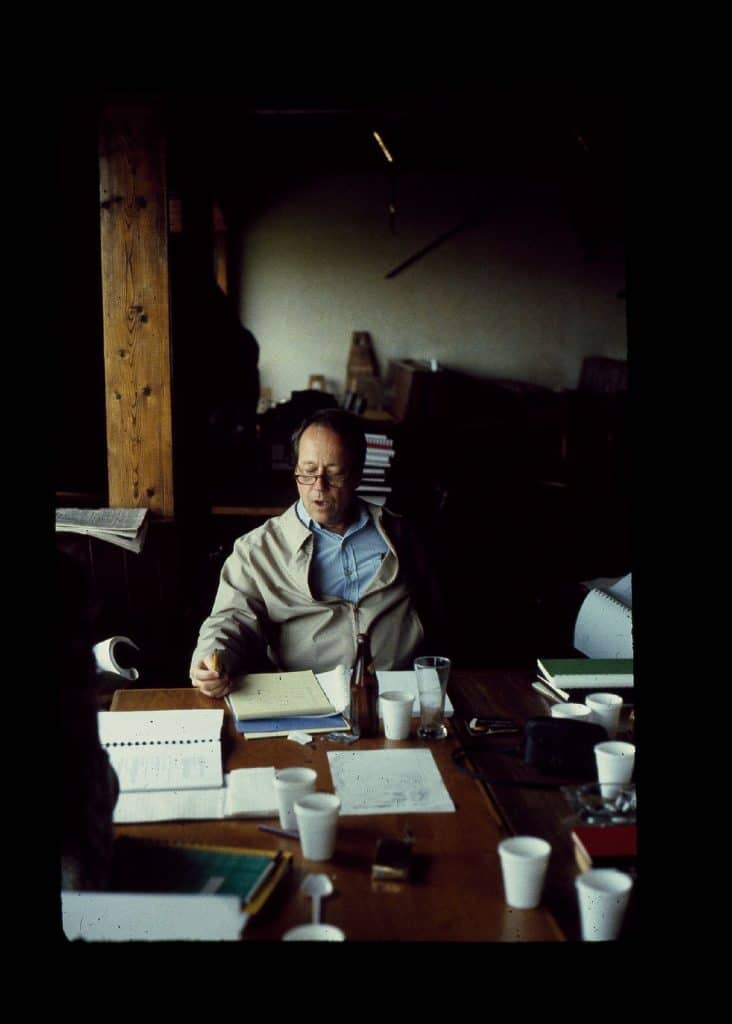

The first time I met him was in the fall of 1988—after I had been led, along with my fellow classmates, into an ancient and somewhat unclean, wood-paneled room where our playwriting Chair, Milan Stitt, was introducing us to each other. There were only four people in each year of the playwriting class, in a three-year program, so it was intimate. At the end of the meet and greet, Milan nodded toward the side of the stage in the direction of a somewhat dapper and pleasant—but still mischievous-looking—gentleman sitting off to the side.

“And of course I need to mention—we are very fortunate to have, as an adjunct professor this year, Mr. George Roy Hill.”

Of course, the name rang a bell, but never in my wildest dreams did I think the actual George Roy Hill would be one of my professors at Yale.

So I just assumed the unfortunate guy on the spindly chair was some ne’er-do-well who had the misfortune of having the same name as the world-famous director of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Sting, and one of my favorites: Slap Shot.

“Poor dude,” I thought. “Must suck being him.”

Within seconds, of course, it was evident that this was the George Roy Hill. Upon realizing that, I felt for the first of many times that I had been admitted to the Yale School of Drama by mistake. What was I doing there?

The brunt of my experience up to that point was putting together a small theatre company in my hometown in New Jersey while simultaneously cleaning the toilets of the arts center that let us use the stage. I didn’t fit in at Yale—not even remotely. I wore a Boston Red Sox hat and Timberland boots. I had a motorcycle and had no idea who Genet was. One of the third years in the program took one look at me after I mentioned I hailed from New Jersey and asked if I came from “farming people.”

My taste ran to narrative-driven, simple stories—hopefully well told—while all around me, cooler and more erudite students were writing plays that were oblique, purposefully remote, and willfully incomprehensible. I was told these plays were “post-modern,” “deconstructed,” and “tonal,” and I had no idea what any of that meant. To be honest, I still kind of don’t.

For the most part, I remember avoiding George at first, as I was just too intimidated to think he might take any particular interest in me or my work. He would come into some of our rehearsals and just lean back on a chair behind us in total silence. Then he’d slink out of the room. It was unnerving, to say the least. I was just happy not to draw any attention from him.

I was writing a play based on a short story called “An Old Time Raid” by William Carlos Williams. Williams was a doctor in my hometown, and the story really resonated with me. It was simple—but only in that way something truly complex is—and I was having trouble rectifying the two dramatically.

Clearly, George saw that too, and when I happened to pass him in the hallway, he stopped me.

“What in God’s name is that play of yours about?”

“What’s it about?” I stuttered back. “Well,” I said, “I’m hoping it’s about a half hour long.”

Dead silence. Then a wicked smile curved along his face, and he guffawed out loud.

I breathed again.

“I’ve got some ideas,” he said. “Come by my abode, 7:30. It’s note time. Oh, and bring your own booze.” And off he went.

“Wait, what?” I thought. “Did George Roy Hill just offer to give me feedback on my play? And drink with him? Dear Lord.”

A dream and a nightmare, all at once.

A dream, of course, because a world-renowned director gave a crap about my little play. A nightmare, because I didn’t drink—and that kind of seemed important to him.

I was in my early twenties then, and even up to that point had never had a proper drink. Like many people, I came up in a household cursed and haunted by alcoholism. My mother had just passed away the year before and had even given me specific directions—from her deathbed, no less: “Don’t you take it up,” she said. “You’d be the worst.”

Looking back now, those words catch in my throat. What did she see in me, or sense I was composed of, that would make me “the worst”? How could she say something like that to her own kid? I remember being angry about it then, but with the gift of perspective and time, I realize now what a beautiful—and honest—gesture it was.

As it turns out, I was able to follow her directive for most of my life—until about thirty years later, when I inexplicably started convincing myself that to take a sip here and there, secretly, of vodka—just as she did—was no different than sedating myself with NyQuil, or weed, or whatever else.

My starting to drink suddenly in my mid-fifties wasn’t because of my environment, or anyone around me, or any particular accelerant. It was the inevitable consequence of skating and denial—of not dealing—and of chickens coming home to roost after years of tamping them down.

At this writing, I’m relieved to say I’m holding steady, but I also realize that besides taking one day at a time, I take minutes and seconds at a time too—and as a result, take nothing for granted.

Back then, however, in 1988, knocking on George Roy Hill’s apartment door and holding in my hand a literal bottle of milk, I had no idea what I was walking into.

He took one look at the goofy bottle, smiled, and asked, “What in God’s name is that?”

“Oh, I don’t drink,” I said.

His face became a canvas of incomprehensibility.

“What?”

“I don’t drink.”

Then something about his countenance settled, and he looked me dead in the eyes:

“Well, goddamn. Good for you. Let’s get to work.”

And thus commenced the first of many amazing audiences with the master himself—me with a bottle of fresh, homogenized Vitamin D milk, and him with something considerably stronger.

An apprenticeship had formed—one I could never have dreamed of when I was cleaning toilets at the Williams Center in Rutherford, New Jersey, a couple of years before.

I remember that first year at Yale flying by way too fast. And as I got to know him better, he let me see the outlines of shadows that he himself was struggling with. Slowly, it dawned on me—the tough place he was in, career-wise, unable to get another film set up, having just had somewhat of a disaster with a sub-par Chevy Chase vehicle (not George’s fault).

He’d asked to direct a Restoration play at the Yale Repertory Theatre, and the haughty directing faculty rejected his offer for whatever bullshit reason. The truth, of course, being he was a tad too successful.

It didn’t help that he would drive up to New Haven in a brand-spanking-new Rolls Royce, given to him as a bonus by Warner Brothers for coming in under budget on the Chevy Chase fiasco.

I would lie awake that first year in New Haven, literally falling asleep to the sound of casual gunfire. The crime was so bad we had to have student “escort shuttles” take us from late-night rehearsals back to our apartments. But George would defiantly park that gleaming silver Rolls right in front of his apartment on Park Street. And no one touched it.

Also during this time, I remember first noticing something off about his gait—and some shakes in his hands and legs, marking the first signs of the Parkinson’s that would eventually claim him.

For me, though, it was a magical year. He taught me the basic elements of story, resiliency, and, most importantly, to have no fear.

I had lost my dad in 1979 when I was fourteen, and it’s no secret George became a father figure to me. Like my own dad, he was larger than life and exuded confidence. And also like my dad, he served in World War II. I knew even then that his generation was slowly slipping away, and I was thankful just to be in proximity to it.

As our time at Yale came to an end, he warned me against going off to Hollywood, but he knew—having taken out huge student loans—that I really had no choice. I would need to. I remember feeling so touched that he seemed worried about me.

I also recall that when I got out to Hollywood a couple of years later, he set up some meetings for me with people who would never have deigned to sit down with a new writer—unless a worried professor three thousand miles away had picked up the phone on his behalf.

In 1996, he came to see my play The Size of the World when it was performed Off-Broadway. I was shocked to hear he knew Rita Moreno, who was one of the stars of the play. Looking back though, of course he would. They were both in New York City for decades and both Oscar winners.

He came to my play in a wheelchair and sporting a very cool beard. His coming to see my work meant the world to me.

Then, one day in 2002, I opened my computer, and the name “George Roy Hill” was all over the internet. Like the first time I met him all those years ago, I hoped against hope that it wasn’t that George Roy Hill. “Please,” I thought to myself, “let it be some unfortunate bastard with the same name.”

But, alas.

I closed my computer and, in my mind’s eye, saw myself standing outside his apartment again. I’m holding a bottle of milk. He opens the door and smiles.

_______________________________

Charles Evered is an award-winning writer and director who graduated from Rutgers–Newark and the Yale School of Drama. A former Lieutenant in the U.S. Navy Reserve, Evered has written numerous plays—many published by Broadway Play Publishing—and is best known for his feature film Adopt a Sailor, which he also directed. The film stars Emmy winners Bebe Neuwirth and Peter Coyote, along with Ethan Peck. The stage version of Adopt a Sailor has toured all fifty states.

In addition to his work in theater and film, Evered has written for television, including the hit series Monk, starring Emmy winner Tony Shalhoub. His upcoming projects include directing the short film Kinda Like Math in Los Angeles (February 2026) and the feature film Lone Pine in Southern Utah (2027).

He is the proud father of Margaret Evered of Richmond, Virginia, and John Evered of Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Evered currently resides in Richmond and Shenandoah, Virginia.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2026 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.