by Sean Parnell

I am a U.S. Army combat veteran. In 2006-2007, my infantry platoon in Afghanistan regularly exchanged fire with Taliban fighters. We had a high casualty rate: I saw my men wounded and killed in action, and I was medically discharged myself, diagnosed with traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder.

My combat service was difficult and challenging. But I’m here to tell you that I was not “broken” or “damaged” by that experience.

It may seem strange that I should feel compelled to declare that fact. But given the ways in which military veterans are routinely portrayed in media coverage and popular culture, we need a corrective to the common view that military service is uniquely psychologically devastating.

But in its modern form, the stereotype really took off in the 1970s, in the painful aftermath of the Vietnam War. Classic films like “Taxi Driver,” “The Deer Hunter,” and “Coming Home” portrayed veterans as tormented souls who were haunted by their war experience. Gradually, the cliché took hold that the warfighter was either, at best, an emotional basket case or, at worst, a tripwire psychotic who might snap at any minute.

For decades, the post-Vietnam experience set the standard for media and popular culture representations of veterans. At that same time, the military branches were moving away from a conscription model toward an all-volunteer force, which meant fewer Americans would experience military service. In the post-9/11 era, it’s estimated that only .4 percent of Americans have served in the military. (I would venture to guess that among working journalists and Hollywood producers and directors, that number is even lower.)

These trends have had an effect that, in hindsight, seems inevitable: communication and understanding between civilians and U.S. military personnel and veterans have eroded. While U.S. troops have been in Afghanistan for 17 years, and in Iraq almost as long, most Americans have no direct frame of reference for understanding what those conflicts have entailed. Thus, they fall back on the stereotype of the broken veteran who deserves their pity—because that’s one story they know.

That breakdown in shared understanding has real effects. Many veterans admit they feel disconnected and estranged from American society upon returning home. They are not “broken” or “damaged” by their service, but they do face unique challenges in reintegrating into a society that doesn’t grasp the cultural gap between the civilian and military worlds. Meanwhile, civilians who haven’t served are uncertain of how to help and may hesitate to reach out to veterans. That dynamic serves no one well.

But we can change that dynamic. It starts with changing the stories we tell about military service and combat and rejecting the exhausted cliché of the broken veteran.

The good news is that we’ve seen a number of efforts to do just that in recent years. For example, best-selling books like “Unbroken” and popular films like “Lone Survivor” and “American Sniper” present narratives of military service that are gripping, vivid, and layered with complexity, with uniformed protagonists who demonstrate skill, commitment, and resilience in difficult circumstances.

I’ve tried to contribute to that new direction in my own storytelling. My 2012 war memoir “Outlaw Platoon” offered an unflinching glimpse of what life is like for soldiers on the ground, to show how the combat experience shapes them.

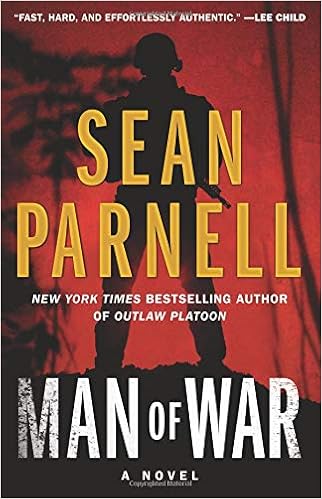

My new novel, “Man of War,” shares many of the same underlying themes of service, sacrifice, and courage. My hero, ex-Special Forces operator Eric Steele, exemplifies many of the best aspects of the warrior ethos. He’s not an indestructible cartoon superhero, but nor is he broken. He’s simply someone who seeks to embody what is best among those who have volunteered to serve their nation.

It’s time for more narratives like this, and I want to encourage other veterans to step up to talk frankly about how their service shaped them for the better. Americans need to hear that side of the story.

For too long it’s been too readily assumed that veterans are damaged or victimized. We need to explain and illustrate how those who have faced combat experience true growth—not in spite of the challenges of their service, but because of those challenges. The vast majority of veterans are stronger for what they have undergone. Our media and popular culture storytelling should reflect that reality. Let’s tell a new story about military veterans.

This first appeared in The Havok Journal on November 8, 2018.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Sean Parnell (@SeanParnellUSA) is a retired U.S. Army infantry Captain who served in Afghanistan with the 10th Mountain Division. He is author of the critically-acclaimed, national bestseller “Outlaw Platoon: Heroes, Renegades, Infidels, and the Brotherhood of War in Afghanistan” and the novel “Man of War.”

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2024 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.