Author’s Note: This article is not anti-award—it’s anti-illusion. Every ribbon has its story. Just make sure the story still matters once the ink is dry and the cameras are off.

_____

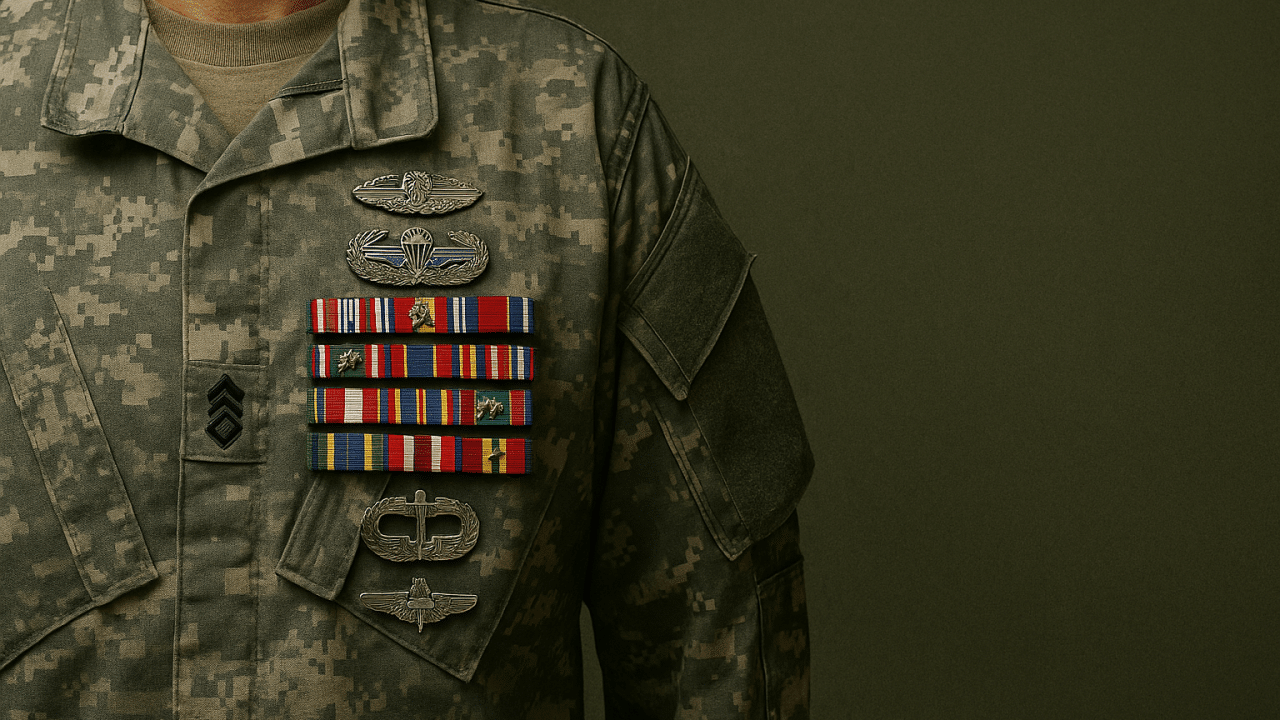

You’ve seen it at every promotion board, change of command ceremony, or motivational poster in the company HQ: a chest full of ribbons, tabs, and badges staring back like a military résumé made of cloth and anodized brass. For many in uniform, the pursuit of that next piece of chest candy flair is as much a part of the career as ruck marches and mandatory fun runs. But what if I told you that this pursuit is driven not just by pride or professionalism, but by a psychological trap first articulated in the 18th century?

Let’s talk about the Diderot Effect, and how it’s alive and well in the military.

What Is the Diderot Effect?

Named after French philosopher Denis Diderot, the Diderot Effect describes a phenomenon in which obtaining a new possession often creates a spiral of consumption. After acquiring a luxurious new robe, Diderot found that the rest of his belongings looked shabby by comparison—leading him to replace almost everything else in his home just to match the perceived standard of the robe.

In short: one new thing leads to a cascade of other “necessary” acquisitions—often with unintended consequences.

Sound familiar?

From Robes to Ribbons: The Military Edition

In military culture, the Diderot Effect shows up the moment that first meaningful piece of “bling” gets pinned on your uniform. These things matter in our profession. After all, no less a personality than Napoleon once quipped, “a solider will fight long and hard for a bit of colored ribbon.” But what does that look like in practice?

🪖 You earn your CIB or CAB in a combat zone.

Now your uniform feels “incomplete” without that Airborne wings slot being filled.

🪂 You get your Air Assault badge.

Suddenly, Ranger School looks less like punishment and more like a necessary “capstone.”

🎖️ You receive an Army Commendation Medal.

Now you notice the guy next to you has a Bronze Star Medal—and a Valor device.

What begins as pride in a hard-earned achievement subtly morphs into a compulsion: the need to fill in every gap, match peers, or outshine that last evaluation photo. This isn’t always vanity—sometimes it’s about keeping up with the perception of legitimacy in a cutthroat system where optics can matter more than substance. After all, Bowe Bergdahl wears something like ten combat stripes. John Kerry received a number of awards for his service in Vietnam before he tossed them back over the White House fence in protest… maybe.

The Rank-and-Award Arms Race

The Diderot Effect can explain not only individual behavior, but institutional ones. Take a hard look at the proliferation of:

- Campaign-specific medals for minor engagements

- Unit awards handed out like candy to avoid hurt feelings

- Badge inflation, where skill identifiers become gatekeepers for promotion, regardless of real-world application

- Beret bonanza–where literally everyone in the Army received headgear once reserved for soldiers in elite units

Each new addition subtly raises the standard of “complete” until today’s baseline soldier looks more decorated than a Vietnam-era colonel.

It’s not that soldiers haven’t earned them—many absolutely have. But when everything becomes a marker of excellence, nothing truly stands out. And we risk shifting the focus from what we do to what we wear.

“Chest Candy” Isn’t the Problem—But It’s Not the Solution Either

Awards and decorations serve a legitimate purpose: recognition, motivation, and esprit de corps. But when they become the primary yardstick of worth, they risk hollowing out what makes the military profession unique—service, discipline, and sacrifice without expectation of reward.

The real danger of the Diderot Effect in uniform isn’t aesthetic—it’s ethical. It’s when soldiers choose schools, assignments, or even deployments not based on impact, but based on the optics of what they’ll earn. They choose to chase “the inner ring,” and often reap the unintended consequences.

Final Thought: Who Are You Without Your Awards?

Strip away the uniform. Who are you underneath the tabs, badges, and decorations?

If your answer is “still a professional, still a warrior, still a servant of the Constitution”—you’ve beaten the Diderot Effect.

If your answer is, “I’d feel less valuable without them”—you’re not alone. But maybe it’s time to reexamine why we chase the next ribbon.

In the end, we should wear our awards the way Diderot should’ve worn that robe: with humility, context, and the self-awareness not to let it redefine who we are.

Charles served over 27 years in the US Army, which included seven combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan with various Special Operations Forces units and two stints as an instructor at the United States Military Academy at West Point. He also completed operational tours in Egypt, the Philippines, and the Republic of Korea and earned a Doctor of Business Administration from Temple University as well as a Master of Arts in International Relations from Yale University. He is the owner of The Havok Journal, and the views expressed herein are his own and do not reflect those of the US Government or any other person or entity.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2026 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.