by Carl Wells

There has been a lot of discussion of late about the US made temporary pier that suffered what I would call a major ‘service interruption’ after high seas in the Mediterranean partially dismantled and damaged the platforms and overpowering the shallow draft boats operating it.

My first thought when I learned about the pending construction was that despite the cost, it was going to be a damn good training exercise. How much does a Brigade rotation to the National Training Center cost? Unless exercises creating a pier and a RO-RO facility are being done somewhere on the Pacific Rim, that I do not know about (very possible).

After the news of the heavy weather dismantling, the question should be raised of how the US is going to fight in the Pacific Theater in areas that do not have functioning harbor facilities. There are major storms in the Pacific also. In December of 1944 Typhon Cobra capsized and sank three US destroyers kill 790 US sailors.

If there is not a major, practiced capability to set up harbor like facilities quickly on small islands or on larger land masses that have had their harbors destroyed or otherwise made unusable, the logistic tail then becomes more vulnerable than it already is. Currently, popular public conversations are about force structure. We ignore the logistics tail at our peril.

Per the DoD, the Gaza endeavor was made up of “Soldiers from the Army’s 7th Transportation Brigade at Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Virginia, and sailors from Naval Beach Group 1 at Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, California, were tapped to deploy the JLOTS capability.”

Delivering the capability involves the complex choreography of logistics support and landing craft that carry the equipment used to construct the approximately 1,800-foot causeway comprising modular sections linked together, which is known as a Trident pier.

The units are also to construct a roll-on, roll-off (RORO) discharge facility that is 72 feet wide by 270 feet long. The discharge facility will remain about 3 miles off Gaza’s shore and enable cargo ships to offload aid shipments at sea prior to being transported to shore.”

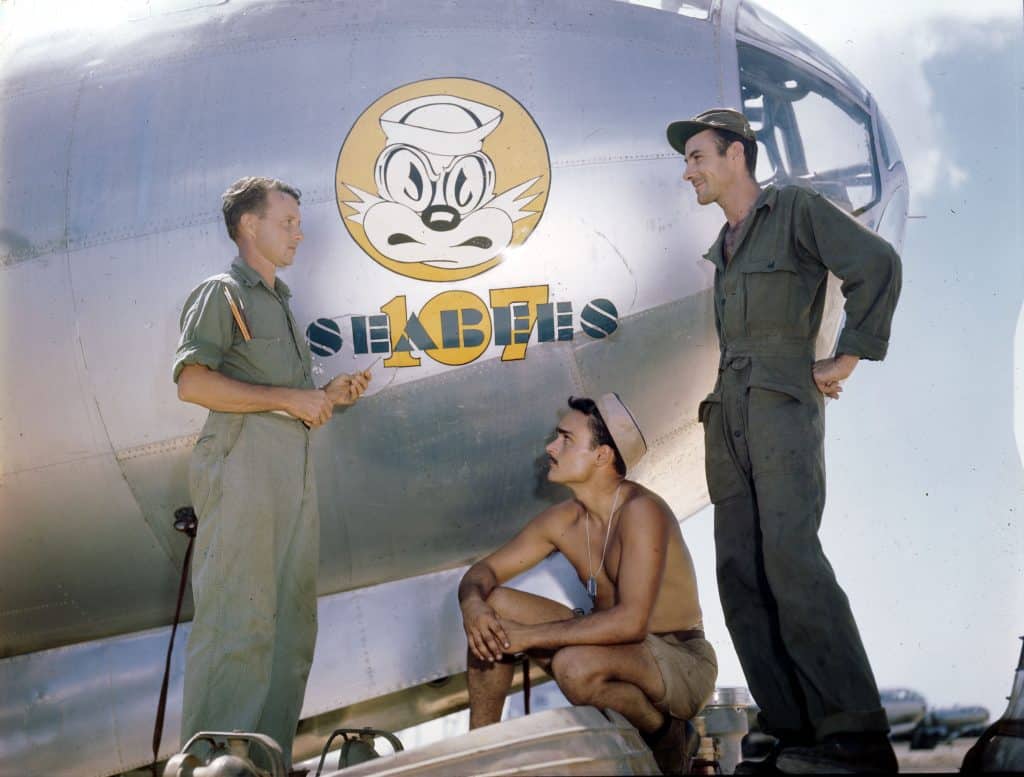

While this was a standard operation in the Pacific by both the Army and Navy Seabees in World War II, it ain’t been done lately that I know of. At first look I believed it would be a straightforward Navy SEABEE mission. In the Navy this would fall to (one would think) the Navy Expeditionary Combat Command (NECC). This is the main command for the SEABEEs or its proper name Naval Construction Forces (NCF). Looking at the mission statements on the NCF and its subordinate organizations, you do not see port construction or repairs specifically mentioned.

1 January 1945. (U.S. Navy Photograph).

That is where the Army 7th Transportation Command comes into play. The 7th Transportation Brigade (Expeditionary) “doctrinal mission is to provide mission command of assigned and attached port, terminal and watercraft units conducting expeditionary intermodal operations in support of unified land operations.” The Transportation Brigade has USNS’s` to carry the components and landing craft needed to build the pier and RORO facility. (United States Naval Ships are unarmed auxiliary support vessels owned by the U.S. Navy and operated in non-commissioned service by Military Sealift Command with a civilian crew. Some ships include a small military complement to carry out communication and special mission functions, or for force protection.) The Brigade is also considered an asset of XVIIIth Airborne Corps.

It has not been disclosed specifically what units from the 7th Transportation Brigade or Naval Beach Group 1 deployed. At least five ships (USNS) deployed to construct the pier. One of which had an engine room fire which required the ship to return to Florida for repair. There has been no mention of what specific Naval units are supporting the effort.

With the 80th Anniversary of Operation Overlord less than a week away there is a historical connection that bears mentioning. The Dieppe Raid of 1942 showed that the Allies could not count on capturing an intact port on the French coast. Cherbourg was the closest port to the landings which was a little over 28 miles or a 30-minute drive from Sainte-Mère-Église, which was behind Utah Beach. Gen ‘Lightening’ Joe Collins led the US Army’s VIIth Corps, made up of the 4th, 9th, and new 79th Infantry Divisions from near Utah Beach to take Cherbourg. The attack on Cherbourg began on June 19th capturing the German Commanding General on June 26th. The battle was horrendously cost for the Americans, losing 2,700 men killed, though the battle bagged over 20,000 German prisoners. The first supplies arrived at the massively damaged port on July16th by LST (Landing Ship Tank or Large Slow Targets depending if you were on one or not). The main port basins were not cleared until mid-September.

The English took the Dieppe Raid lesson to heart and started to plan for something more portable. There were two large Mulberry harbors built by the English to support the Allied Expeditionary Force in Normandy after the landings moved in land. It was correctly estimated that over the beach movement of supplies was insufficient to support allied forces. One Mulberry was off Omaha Beach and the other off Gold Beach. The Mulberry Harbors were designed as floating concrete structures for piers with sunken structures for breakwaters.

The massive storm that struck Normandy on June 19th destroyed the Mulberry off Omaha beach and damaged the one at Gold Beach. With one of the Mulberry’s destroyed supplies had to come directly over the beach’s which could not meet the munition and supply requirements for the allies shrinking at one point to two days’ worth available. This was the impetus for the creation of the ‘Red Ball Express’ of primarily Transportation Companies (mostly black Soldiers) that drove supplies to the front by one route and returned by another. If you remember the Desert Storm unit activation list published weekly in Army Times, it was normally 2/3 or more Independent Truck Companies that drove 5 Ton Trucks and Tractor with flatbed trailers spread all over the United States.

Without a breakwater or shelter of some type for the US constructed pier, it lays open to the Mediterranean. The Med is milder than the Atlantic or Pacific, but still has significant storms as shown last week. Then consider that the Ro-Ro offload point (rolling stock-trucks driving off on to barges) is to be 3 miles offshore which would seem to be even more vulnerable to damage from weather or heavy seas.

It is easy to join the ‘should have’ kibitzers. It serves no purpose though. This has been an expensive ‘training exercise’ (not to mention embarrassing to some and infuriating to others). The question remains is how to protect small piers on remote islands or larger land masses without functioning harbors. They need protection not just from hostile file, but from harsher weather conditions unlike those that are readily available elsewhere. General Winter and Colonel Mud have colleagues.

____________________________

Carl began his military career as a Marine Sergeant stationed in various locations, including Japan and Camp Pendleton, before shifting gears to become an Elementary Special Education teacher and working in EMS in Flagstaff in 1977. Opting out of Marine Corps duties in 1978, he joined the Army in January 1979, directly reporting to the Intelligence School at Fort Huachuca. Throughout the early 1980s, he served as a Middle East Analyst for the 82nd Airborne Division and later aided in preparing the deployment of the first US Battalion to the Multinational Force and Observers in February 1982.

Transitioning roles, he became a Middle East Analyst for XVIIIth Airborne Corps, contributing to Operation Urgent Fury. In 1984, he joined the Ranger Regiment and later attended the University of Maryland in Heidelberg, graduating in 1988. Assigned to 1st Special Forces Command at Fort Bragg in 1989, he found himself deploying to Desert Storm in 1990 as an Intelligence Sergeant. Post-war, he continued his service in various intelligence management roles, completing his MA in International Relations before retiring.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2025 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.