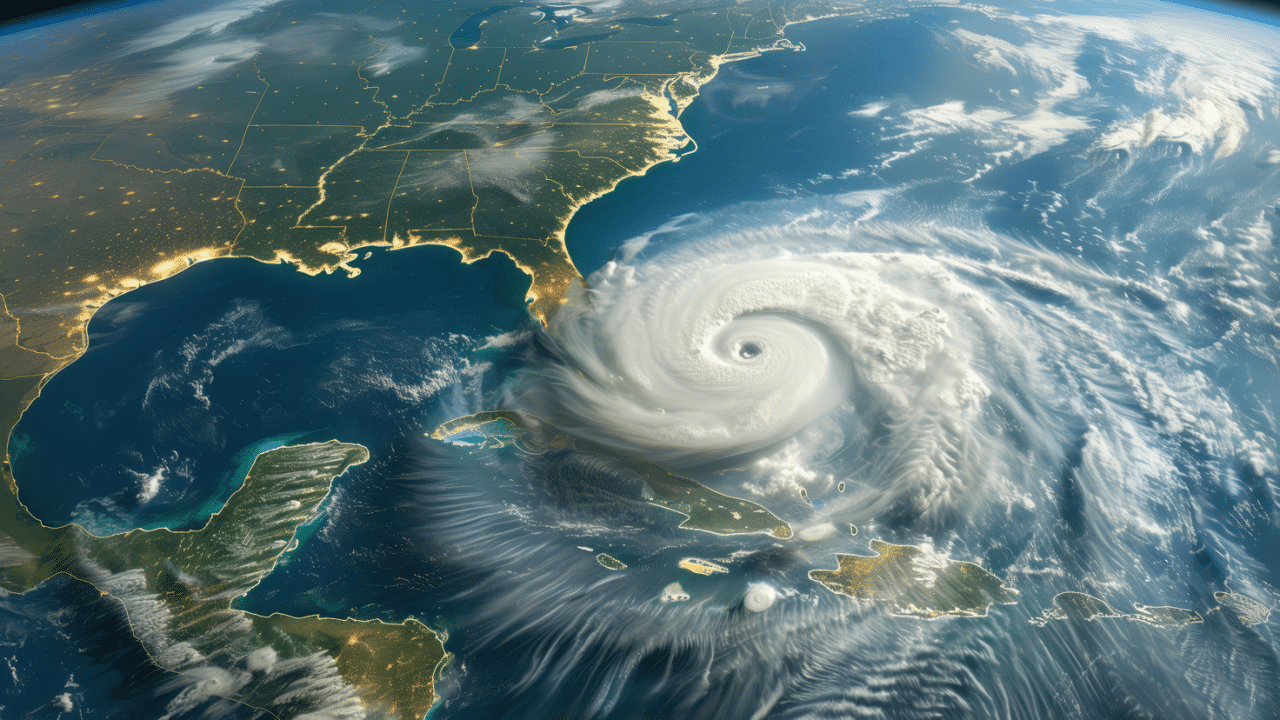

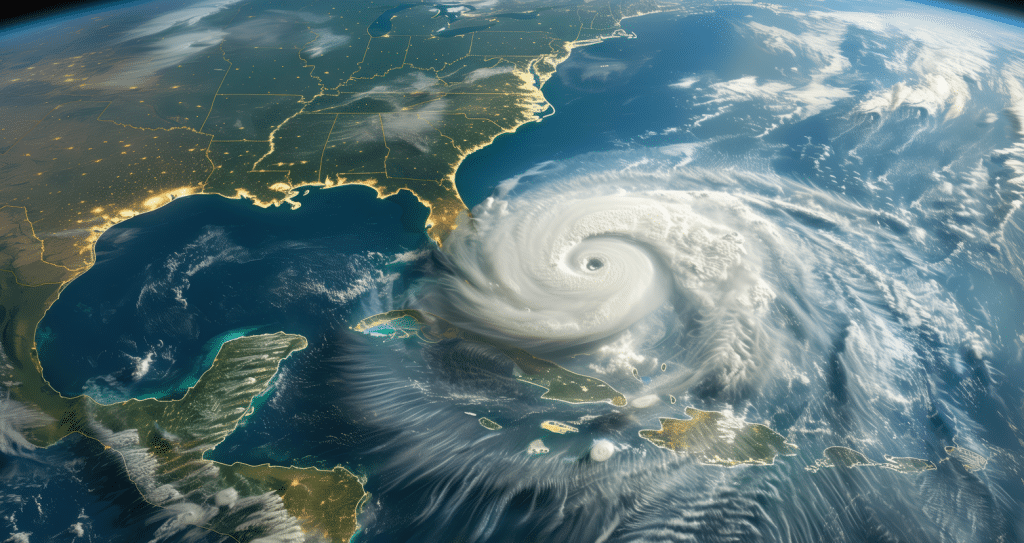

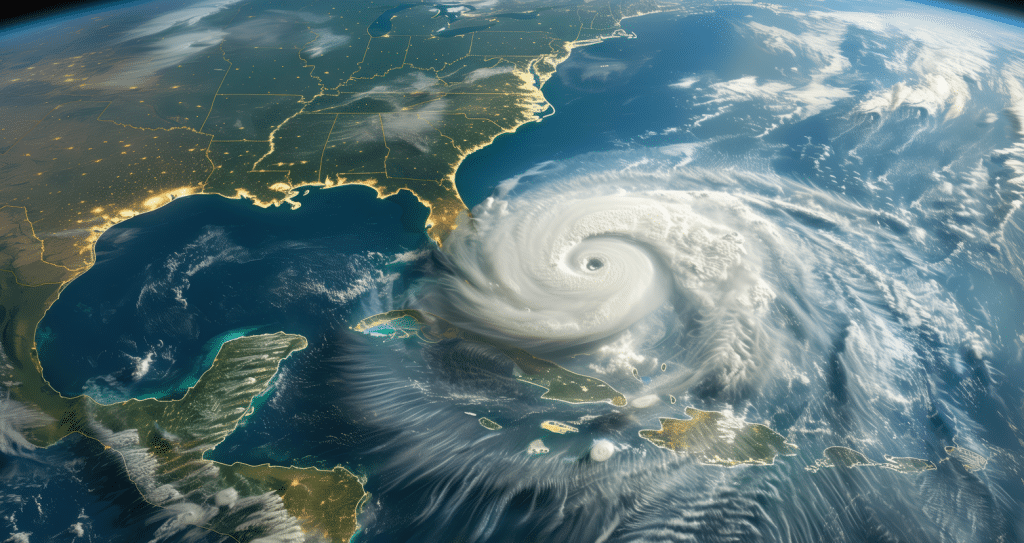

I grew up on the coast of Georgia with the smell of marsh mud and the local pulp mill. During the summer, I’d ski the dark rivers of the coast churning up what looked to be root beer behind our ski boat as the boat driver would eventually run us in circles trying to knock us off our skis or kneeboards. As the heat and humidity of August approached, so did the reality of hurricane season. Brunswick sits in a peculiar spot because the Gulf Stream is about a hundred miles offshore while the Gulf Stream is approximately thirty miles offshore at Cape Canaveral. This makes it unlikely for Brunswick to receive a direct hit from a hurricane since, like hurricane Hugo, they track to Brunswick only to take a right turn and slam Charleston.

My grandmother always insisted I have at least a half tank of gas reasoning that you can always get where you need to go in an emergency with it. As a teenager, I had my car taken away from me on a few occasions because my grandmother checked my gas tank periodically to ensure it was at least half full. Her motive was to always be prepared. Although we grew up with several hurricane warnings for storms that never made landfall, she taught me that it’s not always the storm itself you need to worry about. It’s the period after the storm when the world is tilted sideways as humanity is stretched and we crave the simple things in life, like electricity, air conditioning, running water, and even a working toilet.

My brother Britt and my mother had a close encounter with Hurricane Matthew, which toppled the majestic oaks of Brunswick and St. Simons, snapped and bent power poles like matchsticks, and overwhelmed the sewer system with the sheer volume of water flooding the storm drains. From my brother’s yard, it seemed like you could walk straight from his back patio across the water to his neighbor’s. It looked like a poor man’s infinity pool, with the water’s mirror-like surface sitting still, having nowhere to go. When the National Park Service evacuated us from the far northern wilderness of Cumberland Island due to fears of a backside hit from Hurricane Helene, my brother asked me to stay at his house. I agreed without hesitation. He was worried about the water, but what hit the island was a massive wind event that toppled trees and brought down power lines, much like Hurricane Matthew, leaving residents without power for over a week.

As the wind relentlessly howled through the night, we lost power, and the thick, hot tropical air started weighing down each breath. We weren’t even close to the eye, but we felt Helene’s breath. A few hours after Helene’s winds left us on the coast, she was devastating the western parts of South and North Carolina. Two weeks later, Hurricane Milton struck Florida for the second time, leaving gas stations empty and typical evacuation routes like Valdosta still recovering from Helene. This forced the displaced to drive further north to find shelter from the storm. Looking back over the past few weeks, it’s clear how a hurricane or other disaster can impact one area so differently from another. For this reason, people need to think beyond the initial disaster and be prepared for the weeks, months, or even years it may take to get “back to normal.”

The time it takes for a city to recover from a hurricane or other disaster can vary widely based on several factors, including the severity of the disaster, the city’s preparedness, the extent of infrastructure damage, and the resources available for recovery. Regardless, recovery is not an overnight affair and can differ vastly from disaster to disaster. Typically, remediation is broken into three phases. Getting an understanding of these three phases makes it easy to compare the recovery from different disasters. Here are the typical phases:

Immediate response (days to weeks):

- Rescue operations: The immediate focus is on saving lives, providing medical care, and ensuring public safety. This can take anywhere from a few days to a few weeks, depending on the severity of the storm and the resources available.

- Restoring power and water: Utility companies often work quickly to restore essential services, but in severe cases, power outages and water disruptions can last for days or weeks.

Short-term recovery (weeks to months):

- Clearing debris: Cleaning up debris from streets, homes, and public spaces can take several weeks or even months, especially in highly populated areas.

- Temporary housing: Displaced residents may need temporary shelter, which can extend from weeks to months until homes are repaired or rebuilt.

- Business and school reopening: Depending on the damage, businesses and schools may take weeks to reopen, especially if there is significant flooding or structural damage.

Long-term recovery (months to years):

- Infrastructure rebuilding: Roads, bridges, hospitals, and public facilities may take months or even years to fully restore.

- Housing reconstruction: For homeowners whose properties have been destroyed, rebuilding can take months to years, especially if there are delays in insurance claims, permits, or supply chains.

- Economic recovery: It can take years for the local economy to recover fully, particularly if industries such as tourism or agriculture are severely impacted.

Helene and Milton reminded me that you never experience the same hurricane twice; the effects of one hurricane can vary greatly from another depending on how emergency responders stage relief, the terrain, the time of year, the demographic differences, and whether a community is equipped to handle the disaster. I examined three different storms to illustrate how recovery times can vary significantly. The first is Hurricane Andrew, which primarily struck South Florida; the second is Hurricane Katrina, known for its devastating flood in New Orleans; and the third is Hurricane Matthew, notable for its extensive flooding in the Carolinas.

Hurricane Recovery Comparison

| Andrew | Katrina | Matthew | |

| Areas Affected | FL, LA | LA | FL, GA, SC, NC |

| Immediate Recovery | 4+ weeks | 1 year | 2-4 weeks |

| Short Term recovery | 2 years | 4 years | 1 year |

| Long Term Recovery | 10 years | 15+ year -9th ward is still in recovery | 1-3 years |

Except for Hurricane Katrina, immediate recovery efforts took about four weeks, focusing on rescuing people and restoring power and water. Reflecting on my grandmother’s wisdom, surviving the storm is only the first step. To survive a disaster, you must prepare for the aftermath, particularly during the immediate recovery period.FEMA and weather.gov provide useful lists for starting an emergency response kit, as outlined below. However, these lists recommend only three days’ worth of food and water, overlook some essential items, and do not consider that immediate recovery efforts can take a month or more.

https://www.weather.gov/owlie/emergencysupplieskit

https://www.ready.gov/sites/default/files/2021-02/ready_checklist.pdf

https://www.fema.gov/press-release/20210318/how-build-kit-emergencies

I reached out to Bryan Hunt, an Army veteran and friend who experienced Hurricane Andrew firsthand as a child. With over fifteen years of expertise in emergency response and recovery, he provided valuable insights on how to prepare before a storm for the two to four weeks it typically takes to restore essential services like power and water.

[Editor’s note: Below are Matt’s questions in bold followed by Bryan’s answers in “quotes.”]

When should you get out before a storm?

“The earlier the better. I’ve been through major hurricanes, and staying isn’t for me. I know there are reasons people stay. Sometimes, a loved one won’t or can’t go. Other times, people are worried about their home. I’m not going to judge or fault them. People have their reasons, but if you’re going to leave, leave as soon as possible. You don’t want to get stuck on I75 at the last minute in traffic or not able to get a hotel room or lodging. People were still evacuating during Milton while tornados were touching down. That’s not a good time to evacuate. The earlier you leave, the better the chance you’re not going to be trapped in a bad situation.”

There are a lot of factors that drive our difficulty in responding to a storm. What are some of the natural factors that affect the initial storm response?

“There are a lot of factors that drive the initial response to a hurricane, such as the category and physical size of the hurricane. A compact cat-three storm is different than a wide cat-three storm. How fast the hurricane is traveling is another factor. During hurricane Opal, the storm stalled in Georgia bringing extremely heavy rains while Milton moved rapidly across Florida allowing it to remain a stronger storm inland. Another factor is terrain, like our current situation in North Carolina where mountain roads and deep valleys make it difficult to reach people. The water had to go somewhere, and it traveled down the mountains into the rivers in the valleys below with devasting results. With roads and bridges wiped out, reaching people is more difficult. There are still more factors, but there is one we often miss, and that’s the weather after the storm. Early in the season storms bring relentless heat to an affected region while late season storms can quickly shift from tropical heat to extreme cold if a cold front sweeps down soon after the storm.”

What are some additional things we should incorporate into our emergency checklist when we talk about storm or disaster preparation?

“The first thing I think about is food. Two to three days is not enough. People should look at three or more weeks of food. The good news is there are a number or retailers selling emergency food these days with the very idea that a disaster’s immediate response takes weeks. I’d also have a working cooking source, and it’s important to make sure that everyone in your house knows how to use it. During an ice storm in Aiken, we lost power for two weeks, and while I was out, my wife wanted coffee, but she didn’t know how to use the Jetboil. I was out of the house, and trying to explain it to her was difficult at best. She didn’t get coffee until I was home, and I learned you don’t want to be in a disaster trying to figure out how your disaster equipment works. Everyone in the family should know how to operate your disaster equipment. My final thought is that we think of our houses as these impervious shells of protection. We think, if it’s under the roof, its safe, but if the house gets flooded or the roof gets torn off, everything gets soaked. Keep your essentials, including a few changes of clothes, near you in case your house does get flooded, so you have something dry to change into”

What’s your first advice after a storm when cleaning up?

“Secure your house first. If there are downed power lines in your yard, stay away from them. If a powerline is touching a puddle of water, assume it’s live and don’t touch the puddle. After securing your house, see what your neighbors need. The real first responders in a disaster are the people around you. A neighbor may be trapped in their house or need their driveway cleared. Knowing your neighbors before the storm is also important. Do you have older neighbors or neighbors with disabilities that may need your help? Are you disabled or elderly? The first moments of a disaster, it take a village. If you don’t know your neighbors, get to know them.”

[Author’s note: Bryan was on the mark about knowing your neighbor. 46% of people surveyed by FEMA said they would need to heavily rely on a neighbor for help in the first 72 hours after an emergency.]

If my home gets flooded during the hurricane or there is other substantial water damage, what should I keep?

“Mold is the major problem in everything, even your clothes. People think it’s just in the walls, mold can grow on all sorts of things. If you can’t get clothing immediately clean, you’re going to end up throwing it out. Once mold is there, it’s there. Once mold is in your clothes, in fabric, you can’t get it out. You’re an Eagle Scout, you slept in those summer camp tens with that slight moldy smell and gone on multiple week hikes where you didn’t focus on trying your tent out, you focused on putting on miles. Look how quick mold formed on those tents. When they got moldy, was it easy to get the mold out? “

How do you know if someone is legitimately helping you or scamming you after a hurricane?

“If someone is trying to pressure you into using their services immediately, they’re probably scamming you. Don’t fall for the guy with the list of eight or ten clients that he can try to work you into if you act today. Also, check to see if they have a legitimate business license as well as insurance. If they don’t, walk away.”

I had a few more questions for Bryan, but I’m saving those for another article. There are a few key points that came out of my research and interview with Bryan. Perhaps the most important is that three days of food and water isn’t enough. We focused on hurricanes in our discussion, but with any large, sudden disaster, the first responders are those at ground zero and that could mean you!

Keep important survival gear near you during a hurricane or other potential disaster events. It’s not a lot of help if you can’t get to it. Finally, be prepared. Be prepared to leave quickly, be prepared with a heat source, and be prepared by making sure your entire family knows how to use your survival gear. Be prepared to respond to your community and be prepared to wait.

______________________________________

Matt is a Director of Product Management for a leading mobile platform enablement company. He has traveled extensively in the United States and overseas for business and travel. His travels include India, Mexico, Europe, and Japan where he was an active blogger immediately following the Kaimashi quake. Matt enjoys spending time outdoors and capturing the world through the lens of his Nikon D90. He enjoys researching the political, economic, and historical influences of the places he visits in the world, and he commonly blogs about these experiences. Matt received a Bachelor in Computer Science at Mercer University, and is a noted speaker on innovation, holding over 150 patents. His remaining time is spent with his family going from soccer game to soccer game on the weekends.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

Buy Me A Coffee

The Havok Journal seeks to serve as a voice of the Veteran and First Responder communities through a focus on current affairs and articles of interest to the public in general, and the veteran community in particular. We strive to offer timely, current, and informative content, with the occasional piece focused on entertainment. We are continually expanding and striving to improve the readers’ experience.

© 2026 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.